In his previous life, people gave their trust to J.P. Dyal as their financial adviser, to plan their dreams of getting a home, a car, a stable future.

He climbed the corporate ladder, owned businesses, helped others launch theirs, but was married to a job that consumed his life at 80 hours each week.

Then, in 2008, the Great Recession cast him adrift with a divorce as well as the loss of his job.

Dyal, now 44, had to reinvent himself — but nothing in his past prepared him for the life he has come to embrace.

He found his salvation and a new passion because of his Ego.

That was the name of the mustang he owned. Originally, a friend adopted Ego, a 6-year-old mare, but she was not able to ride her even after hiring a trainer. Dyal began training her himself and after three months of hard work was able to ride her safely. It took a year before it was safe enough for other people to ride her.

“Riding Ego was therapeutic, and I rode her almost every day,” he said. “After a while training her became natural,” although he also consulted with experts and went to training clinics.

Before he knew it, Dyal was approached by other horse owners who found out about his newfound skills and sought his help.

His transition was not something he planned: “It kind of happened.”

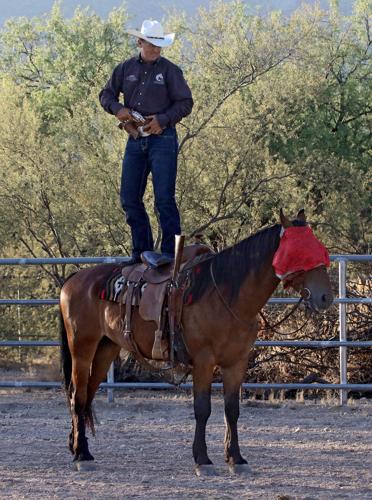

For eight years now, as a colt starter, he has taken halter-broken horses and taught them so they can be ridden.

Mustangs, the classic symbol of the American West, have a special place in his heart:

“They saved me and I haven’t let them go since.”

A clean slate

“Working with mustangs is like working with a clean slate. They are something that is wild … it’s never been handled,” he said, adding, “When a horse allows you to touch it, that horse has let you into its life.”

Dyal works long physical hours, from dawn to late in the evening, working mostly alone, almost every day. He is always trying to make ends meet.

It’s a life his parents, especially his father, don’t quite understand, and it is certainly nothing like his life in Florida, where he grew up in Fort Lauderdale and around the Keys. Dyal was raised on a bay where his family had a boat, watching ships of all sizes come and go. Then he went off to Auburn University and set course for his life in corporate America.

By 2015, his unlikely second calling found him in Tucson at the White Stallion Ranch. Then, after a brief period of training mustangs in the Chiricahua Mountains, he returned here this past February.

Along the way he came across his first Extreme Mustang Makeover event in 2009, as a spectator.

Created by the Mustang Heritage Foundation, in cooperation with the Bureau of Land Management, the makeover is in its 11th year of competition, taking place in 10 cities.

It challenges, almost dares, horse trainers across America to tame a mustang that has been virtually untouched by human hands.

From wild to gentle

By the time competition starts, the horses must be accustomed to wearing and being handled using a halter, and they have to be saddle-trained. But that is not the hard part. The hard part is that it must be done within 100 days.

The mustangs are from 10 Western states, including Arizona, from short- and long-term corrals and pastures managed by the BLM. The agency has more than 46,000 wild horses and burros in its care, the Interior Department says.

The BLM rounds up mustangs regularly, partly so that remaining herds in the wild have plenty of food and water. The captured horses need new homes.

“It is critical that we bring awareness to the opportunity of adoption,” said Kali Sublett, the executive director of Extreme Mustang Makeover.

“The EMM events were created to showcase the trainability and adoptability of American mustangs while also providing the public with the opportunity to adopt a gentle mustang,” she said.

The competitions are entertaining, but the goal is for attendees to walk away with a better understanding of the situation for American mustangs, Sublett said.

“By offering ‘gentled’ animals, we are ensuring that the transition from wild to private care would be less intimidating for both the mustang and its new owner,” she said.

Trainers compete for cash and prizes, but the ultimate goal is to find their horses a home through adoption at the end of the competition.

Since 2007, when the makeover competition began, the foundation has been to 34 cities and 23 states, providing homes for more than 9,000 mustangs.

“It’s flirting with a fine line, because you are cramming a year’s work in 100 days,” Dyal said, adding, “It’s the ultimate in horsemanship.”

Bonding with Moose

The horses are assigned randomly, and that’s how Dyal was recently paired with Moose.

To make the challenge even harder, Moose, a 6-year-old mustang from the Owyhee herd northeast of Reno, Nevada, came with a deep gash on his nose that went clear to the bone. It was thought to be life-threatening because it became infected.

“I was afraid that if I returned him he would be euthanized,” Dyal said.

Dyal found himself without the resources to pay for Moose’s much-needed operation. Then, help came from some of the veterinary staff workers at Rogers Bandalero Ranch, at 8526 E. Tanque Verde Road, where Moose was staying.

Moose’s fate might have been different, said Alicia Lindholm, a veterinarian who worked on the mustang. The injury was well past the usual time frame for a successful closure, she said. The combination of Dyal bringing him to be treated and the horse’s willingness to cooperate made a difference, she said. Moose’s attitude also allowed for him to be sedated so his injury could be cleaned and treated.

It may have been the severity of the injury, combined with Moose knowing people were trying to help him, but he seemed to trust Dyal without question. Before long, Moose was following Dyal around the stables, shoulder to shoulder wherever he went.

“I can’t explain how trust is developed,” Dyal said. “It’s an energy, some unseen energy that I can’t put into words. It is an incredible feeling of acceptance.”

At the same time, it is fragile and can be damaged, he said.

“When I first started training horses, I had to start thinking the opposite way a person normally thinks because we are predators and horses are a prey animal.” Horses are used to being chased and their first instinct is to run to avoid conflict.

In training they learn through nonverbal means of communication, such as the release of pressure, Dyal said. That could mean releasing tension on a lead rope attached to the halter after the horse responds correctly to a command. Even turning your back on a horse helps to release pressure.

Dyal eventually nurtured trust by blindfolding Moose during parts of his workouts, a technique enabling the bond to flow between rider and horse, he said. It is not a technique he uses right away. He blindfolds a horse when he wants to take it to higher level.

After some time, a horse trusts Dyal as it begins to understand that no harm will come to it. Each step it takes makes the horse rely on the rider. It then becomes confident and begins to communicate on a more sensory level, paying more attention to the rider’s leg pressure, to sounds and to surrounding smells, he said.

A home for moose

The long workouts, sometimes twice or three times a day, may be the reason Dyal and Moose took fourth place in a field of 22 riders and horses last weekend at the makeover competition in Reno.

As a result, Moose has found a new home at Hunewill Guest Ranch in California.

“He is super-mellow and kind of gentle and J.P.’s a great trainer,” said Megan Hunewill, whose family started the working ranch in 1861, then turned it into a guest ranch during the Great Depression.

Mustangs live a long time, they are durable, sure-footed and smart and they take care of people, Hunewill said.

“Moose is just what we were looking for,” she said. “He will have a long life here.”

Accomplishing the goal of helping Moose find a new life is its own reward for Dyal because now, after so much time, he can appreciate how his own life has been transformed.

“The money might have been great” in his past, he said, “but you don’t get the same reward or the feeling of happiness that you find when working with a wild animal.”