Education data gleaned from standardized testing can be powerful in pedagogy and strategizing, but there are stories behind every percentage, every ratio. Ironwood K-6 Elementary School could be considered a good example of that.

Marana’s Ironwood Elementary, near North Thornydale and West Overton roads, has had historically strong Arizona Department of Education state testing performances, typically hovering around a “B” grade.

That track record was marred soon after the pandemic, when the school received a “C” grade from the state for the 2021-22 school year. Arizona school letter grades are based on, among other things, academic growth and proficiency.

The school had received a one-two punch from remote learning and the opening of nearby Dove Mountain K-8 school.

Because the schools service area decreased, Ironwood’s student body plummeted from about 650 students to 400, said Ironwood Elementary principal Aaron Johnson — but it was more than student enrollment.

“It doesn’t take a demographer to figure out that Dove Mountain has higher socioeconomic families,” Johnson said.

As of 2021-22 Ironwood still did not receive federal Title I funds, which are reserved for schools who have at least 40% of their students from low-income families. Title I distribution can also be based on the number of students who qualify for free and reduced-price school lunch.

Marana Unified School District’s state report card did not have 2022-23 Title I numbers available.

According to Ironwood’s 2021-22 school report card, student groups with the lowest proficiency percentages in English language arts were special education students (90% minimally proficient in English language arts), economically disadvantaged students (46% minimally proficient) and Hispanic students (47% minimally proficient).

The same groups showed the lowest proficiency levels in math as well; 66% of special education students were minimally proficient in math, 37% of economically disadvantaged students were minimally proficient and 44% of Hispanic students were minimally proficient.

“We didn’t feel like (the C grade) told the real story of how smart our kids are and how capable they are.” Johnson said.

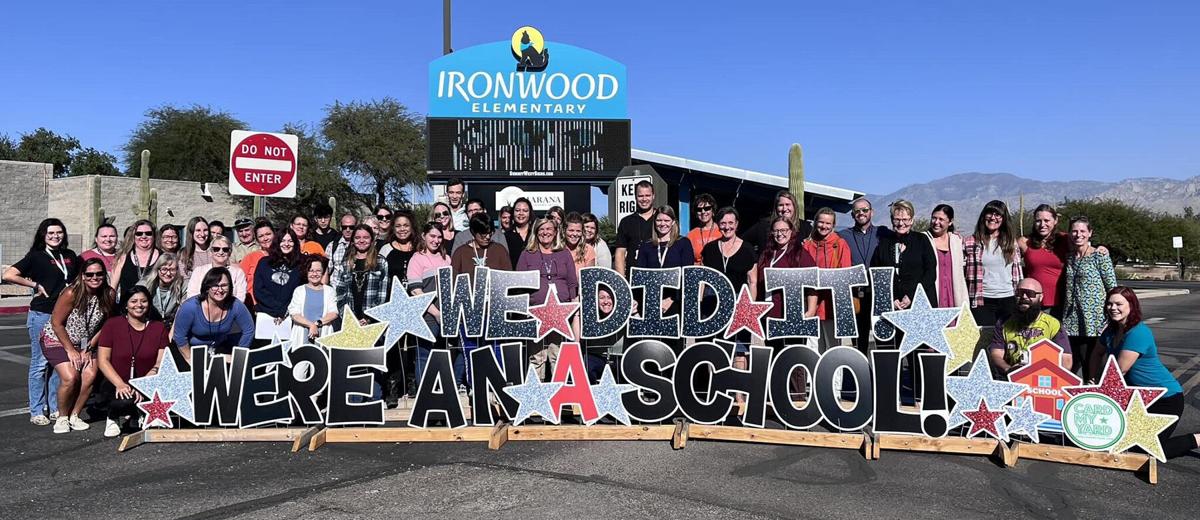

What a difference a school year makes. Ironwood received an A in 2022-23.

Hispanic students and economically disadvantaged students improved their proficiency in English language arts to 33% minimally proficient and 41%, respectively.

In math, as Hispanic students improved to 31% minimally proficient as a group.

Economically disadvantaged students improved marginally, the group being 34% minimally proficient in math.

(Special education students were not reported on. The department of education does not release numbers for subgroups whose members number ten or fewer students, or subgroups whose members have the same scores. This is to protect students’ anonymity.)

Progress wasn’t easy, though, Johnsons said. The school’s faculty, staff and district administrators gave Ironwood a curriculum makeover.

The school implemented a board-approved English language arts program, with consumable materials like journals and workbooks, along with online reading, games and an online library.

A greater emphasis was put on phonics, following the recent science of reading movement.

Ironwood fourth grade teacher Robin Mau said the teachers racked their brains to come up with new, creative teaching methods.

However, the secret sauce, according to Johnson, was creating a positive, enthusiastic learning community.

“It was explaining, talking to kids and saying, Do you feel like we’re an average school? Because I don’t, and you don’t feel that way either,” Johnson said. “We think we have an amazing school, and so if you feel that way, then we need to show everybody outside of our school how awesome we are.”

Mau noted that if students don’t show up for school, they don’t learn. “It’s creating a culture where the students want to be here. I’m a very hands-on teacher. I try to do a lot of activities that get them excited about learning.”

“The idea that takes a village is 100% accurate,” Mau said. “As a teacher, we couldn’t do it without our aides and without our parents and without our administrators.”

Students and staff celebrated their school when the A grade was announced, Johnson said. Different groups learned of the grade at different times, but the school also held an assembly to recognize Ironwood’s achievement.

Ironwood’s circumstances the years from its C grade to it most recent A grade show that adjustments at the school level can make a big difference. Still, tests results are often only as good as the quality of the test itself, which certainly has flaws, both Johnson and Mau said.

Mau indicated she had few good things to say about mandated standardized testing, but did say being able to track cohorts can be helpful.

“We can look at (student groups) the next year and track that same group’s progress over time, but it’s never going to be exactly the same group.”

A marginal amount of time is spent teaching students different types of questions, Johnson said.

“Leading up to state testing, we now schedule time with every single class with myself, my associate principal, my instructional coach going into every classroom,” he said. “We spend some time playing around with the tools on the sample test, so when kids finally do get to the test, it’s not like, What does this button do? We are eliminating some distractions that might come up.”

The different types of questions, like multiple choice and true/false, can seem like test developers are trying to “trick” students, Mau said.

“Part of that becomes, are we really trying to measure what our students know, or are we trying to trick them?”

For now, though, schools must work with the quantifiable data they can get, because love them or loathe them, state grades matter.

“When they call it high stakes, they’re not joking,” Johnson explained. “This impacts everything. People want to move into an area with an A school. They don’t want to move into an area with a D school.

“The ripples go far.”