The Verde Mining district grew to become one of the greatest copper producers in Arizona from 1883 until 1992. Two primary mines produced more than 99% of the district’s copper production: the United Verde and the United Verde Extension, also known as the UVX.

The district, located on the northeastern slope of the Black Hills (Mingus Mountain), has an intricate geologic history dating back 1.74 billion years. Its abundant mineralization was formed by metal rich black smokers, classified as hydrothermal vent chimneys, along the seafloor.

This is in contrast to many of Arizona’s copper deposits to the south, which are classified as porphyry copper molybdenum deposits, formed less than 180 million years ago by hydrothermal fluids originating from an underlying magma reservoir.

The volcanic massive sulfide deposits of the Verde Mining district are described as small, compact and exceedingly rich ore bodies compared to the large, low-grade disseminated qualities of the porphyry copper molybdenum deposits.

The Verde Valley has a long history of mineral exploration and mining dating back over 1,000 years ago to the Indigenous people affiliated with the ancient Tuzigoot pueblo, located 7 miles northeast of the present town of Jerome, who were attracted by surface mineral outcroppings.

Small excavations along with stone hammers were evident and recorded in the area, as noted by Spanish explorer Antonio de Espejo in 1582, who was guided there by local Native Americans.

Diego Pérez de Luxán, a member of the expedition, noted the prevalence of copper with no traces of silver. Another visit in 1599 by Spanish explorer Capt. Marcos Farán de los Godos described the vein as wide and rich with many outcrops composed of ores. Average depth was described as three estados (one estado, according to Spanish explorers, represented the height of a man).

The prevalent blueish green copper minerals were used for personal adornment and coloring for blankets and pottery by Native Americans.

Despite these discoveries, the Spanish did not have the resources involving labor or capital, along with a viable market based upon the technology at the time, necessary to exploit the deposit for profit.

Several hundred years later, after the Mexican War culminated in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848, the United States government acquired jurisdiction over the area. The emergence of Prescott 35 miles to the southwest as both territorial capital and supply hub in 1864 increased mining activity in the region.

Al Sieber, a renowned prospector and chief Army scout, was noted for having located one of the first mining claims in the Verde area in 1876. Christened “Verde” because of the rocks’ green carbonate stain, the area attracted other prospectors around the same time.

These included Morris Andrew Ruffner, John Dougherty, John D. Boyd and Josiah Riley, who were credited with having discovered what became known as the original United Verde Claims comprised of the Eureka and Wade Hampton, located around the upper reaches of Bitter Creek Gulch north of the present town of Jerome.

Ruffner obtained capital from financial partners George and Angus McKinnon to develop the mine until they sold their interests to territorial governor of Arizona Frederick A. Tritle, whose mining ventures were in turn sponsored by financial interests in New York which included James A. McDonald and Eugene Jerome.

The district was visited by James Douglas, a metallurgist, on behalf of the interests of two Philadelphians, J.P. Logan and Charles Lennig, in 1880. Douglas, though impressed with the mineral potential of the property, noted its remoteness regarding ore transport from the nearest railroad 180 miles distant and advised against the purchase. Douglas would later partner with Phelps Dodge to develop copper mines in Morenci and Bisbee in Southern Arizona. Lennig would proceed to purchase the Eureka claim.

The United Verde Copper Co. was incorporated in 1883 with James A. McDonald its president. That year, the town of Jerome was established on the steep northeastern slope of Cleopatra Hill at an altitude of 5,435 feet. It was named after New York banker Eugene Jerome, who invested $200,000 to develop the property.

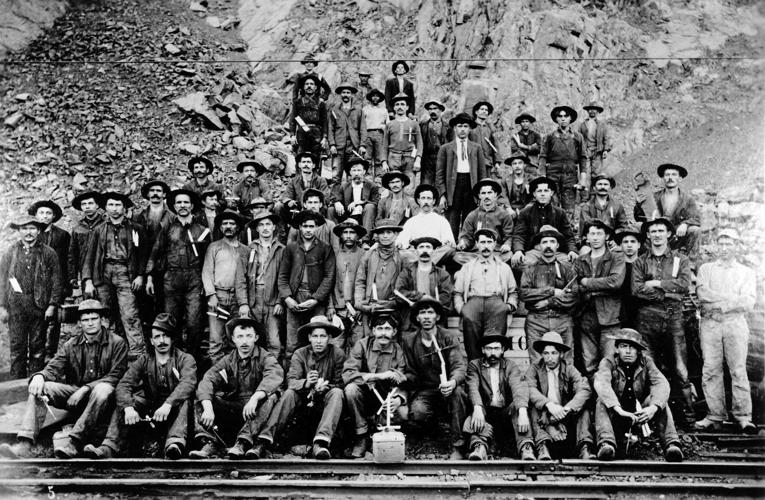

Mining operations commenced at large scale under the lease held by Tritle with the erection of the first reduction furnace. A wagon road for supply transport by mule team costing $19,000 was financed by the Yavapai County government and built 60 miles north to Ash Fork, an access point along the Atlantic Pacific Railroad completed the year before.

Douglas again visited the mine in 1887, recommending its purchase to Phelps Dodge, which had acquired an option on the property. Purchase efforts were stymied by lengthy monetary negotiations with Lennig, the mine’s principal creditor, which included a last-minute $300,000 increase in price wherein the option was dropped. The property was immediately snatched up under a two-year purchase option by William A. Clark, who purchased its entirety in 1890.

Since the early 1870s, Clark was already an established copper king in Butte, Montana, having held mining properties that included the Travona silver mine, Colusa, Gambetta, Mountain Chief and Original. He became interested in the United Verde Mine while serving in the capacity of commissioner representing Montana at the New Orleans exposition in 1885. It was there that United Verde Mine mineral samples were on display and Clark noted their assays which included gold and silver associated with copper. It was under his guidance that the mine finally prospered.

Clark monopolized the mine’s stock during his 37-year ownership with the exception of James A. McDonald (former president of the United Verde Mine), who owned the remainder until it was purchased by Clark’s heirs years later.

Joseph L. Giroux, superintendent of Clark’s Montana mining operations, was sent to Arizona to survey and make improvements to the property which included transport and ore processing. A new smelter consisted of several 160-ton, 48-inch-by-240-inch blast furnaces that treated 1,000 tons of ore per day. In addition, a reverberatory furnace was added to treat gold and silver values from flue dust and ores along with adjacent mine shops and offices all built over the ore body (determined to be 800 feet wide and 1,000 feet long) valued at 20% copper glance (chalcocite).

Mining operations would continue to prosper into the 20th century despite challenges such as fires, unstable ground, transition from underground operations to open pit, and competition from other mining interests in the district that sought to discover neighboring ore bodies or exploit an extension of the United Verde. Read about those in the Star’s next Mine Tales column, on Sept. 12.

Collection: Read more from the 'Mine Tales' series

Arizona has many historical mining properties that have produced gold, fluorspar, vanadium and uranium. These minerals have proven vital to ma…

Many of the mountain ranges near Tucson made significant contributions to Arizona mining history. These including the Sierrita, Silver Bell, Patagonia and Santa Rita Mountains.

From 1883 through the early 1970s the production history in the Turquoise Mining district included ore, copper, lead and zinc and turquoise.

The Sierrita Mine, southwest of Tucson, is currently the only internal U.S. source of rhenium, a metal used by the aerospace industry

Arizona is known to host 992 valid mineral types and no doubt more will be discovered in the future.

Here's how they played an important role in the geologic history of Arizona.

The Verde Mining District area attracted other mining ventures, including the development of the United Verde Extension Mine.

The United Verde and United Verde Extension Mines produced over $4 billion in recovered metals in Arizona's Verde Mining District.

Mohave County is known as the second-highest gold producing county in Arizona, behind Yavapai County.

The purpose of these missions was to aid in the colonization and exploration of land to the financial benefit of the Spanish Empire.

The land that was to become Arizona territory in 1863 and a state in 1912 was, for centuries before, a destination for multiple Spanish explorations in search of gold, and also served as a prominent area for notable silver processing techniques — and stories of lost treasure.

Arizona’s mines and their history have contributed to the backdrop and premise of some remarkable films, from Hombre to Edge of Eternity.

Underground mining operations have had to deal with development challenges including drainage, ventilation, illumination, and excavation support.

Petrified Forest National Park is world- renowned for its petrified wood deposits, but much less known for its mining history and potash deposits.

Mining in the Dos Cabezas Mountains has a long and varied history of successes and failures based upon mineable resources, metal commodities a…

The Lakeshore copper deposit 32 miles south of Casa Grande in Pinal County, while showing enough promise to attract a succession of investors …