Arizona’s water chief is offering a new path out of the morass in Colorado River negotiations — a proposal to tie future water releases from Lake Powell to Lake Mead on what’s actually in the river, rather than what forecasters predict will be there or century-old allocations said should be there.

Tom Buschatzke’s proposal would base annual releases from Powell to the three Lower Colorado River Basin states — Arizona, California and Nevada — on a fixed percentage of the average amount of “natural flow” down the river over three years.

It offers a radically different — and to some observers, more sustainable — method for how to determine the annual releases compared to traditional methods that the states and federal government have relied on for decades. Those methods have been held by many scientists to be directly responsible for the basin’s failure to bring water use in line with the shrinking supply.

In the long run, Buschatzke’s proposed method is more likely to protect the river’s health and lead to a balance of its supplies with demands, said Eric Kuhn, a longtime river researcher, and David Wegner, a former longtime U.S. Bureau of Reclamation official.

Tom Buschatzke

The amount of water allocated for sending to the Lower Basin and for being kept in the Upper Basin would be calculated over a shorter time frame and be more reflective of real-time water supply data, said Wegner, who sits on a National Academy of Sciences advisory board on water issues.

The key to the plan’s success, however, will be what percentage of the available supply averaged over three years is made available for allocation to both basins, he said. That percentage would have to be negotiated by all the states before it’s formally set.

“If the percentage made available for allocation to the states is too high, the demand will take more water than is sustainable,” Wegner said.

The proposal is also seen by some outside water experts as a potential fix if not a breakthrough for the protracted, stalemated negotiations between the three Lower Basin states and the four Upper Basin states — Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming — over how to match water demand with supply.

It’s also the first proposal that’s been discussed in the long-private negotiations to become public in some time. Buschatzke, director of the Arizona Department of Water Resources, made the proposal public Tuesday at a meeting in Phoenix of an advisory committee that is helping ADWR come up with solutions to the river’s ongoing water crisis, including gaps between supply and demand.

The idea has received generally positive reactions from outside experts and one Colorado water official, although key details remain to be worked out, and that won’t be easy.

“It presents an attractive alternative to the increasingly baroque and unproductive s—-show that had taken over interstate negotiations,” New Mexico-based water researcher and author John Fleck posted last week on his influential Inkstain blog.

So far, there’s been no public opposition from any of the four Upper Basin states. A representative of one of them, Colorado, seemed at least cautiously receptive to it in a statement Friday to the Arizona Daily Star.

It’s also seen by many observers as a way out of the dispute now brewing between the two basins’ water officials over whether the Upper Basin states will soon be in violation of the 1922 Colorado River Compact’s requirements to deliver a minimum amount of water over 10 years to the Lower Basin. If Buschatzke’s plan was adopted, that issue would be placed on indefinite hold.

CAP director’s warning

That could be a timely move, because at Tuesday’s committee meeting, Central Arizona Project General Manager Brenda Burman warned that by the end of 2026, the Lower Basin states may for the first time receive less river water over 10 years than the 82.5 million acre-foot minimum release of water they say the compact requires the Upper Basin states to send them.

The Upper Basin states sharply dispute the argument that they must release 82.5 million acre-feet over 10 years. They say they won’t be in violation in any case because the compact only requires them not to deplete the river. They blame depletion on climate change, not their own water use.

But Berman warned that in 2027, the Upper Basin releases could fall further behind what’s needed to meet compact rules, unless the Upper Basin sends down 9 million acre-feet from Powell to Mead — an amount the Lower Basin states haven’t received in years. If the release is 8.23 million acre-feet, “the compact will not be met. We drop below that line. And anything less than (8.23 million) leads to a more marked deviation from where we feel we need to be.

“This projected deficiency is important for us to understand. There is a lot we think needs to happen to prevent that. We are all trying to take on risk in this basin to find a settlement, so we can all continue to thrive,” said Burman, a former U.S. Bureau of Reclamation commissioner.

Forecasts often too optimistic

Buschatzke’s proposal would base annual releases from Powell on a three-year average of how much water naturally flows downriver from Lee Ferry near Lake Powell.

Lee Ferry is a little-known spot on the river lying about one mile downstream from the better-known Lee’s Ferry, which itself is at the Colorado’s confluence, about 9 miles downstream of the Arizona city of Page that borders the lake.

Buschatzke’s proposal comes in sharp contrast to the way annual water releases have always been determined, at least since 2007. That’s when the seven river basin states first agreed on a plan to operate the river’s reservoirs.

Every year, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation decides how much water to release from Powell based on what its forecas ts say are likely to be in lakes Powell and Mead by a given date. The idea was to balance water levels at the two big reservoirs to keep them reasonably functional.

The amount of water released from Powell to Mead determines how much river water Arizona, California and Nevada get each year.

But too often, those forecasts have proven too optimistic, helping to encourage excessive water use that has depleted the river and lowered its reservoirs. Also, that system has pitted the Lower Basin states against the Upper Basin states in almost constant conflict about how much water should be released.

The Colorado River flowing through the Grand Canyon. Arizona’s water chief Arizona’s water chief is offering a new path out of the morass in negotiations over how to bring river usage in line with available supply.

In an interview, Buschatzke said “natural flow” means the amount of water that Mother Nature would be providing in the river “unfettered by any human intervention.”

“It’s as if there is no human influence, no use of water, no reservoirs, just flows of the river, unfettered by any human intervention. You back out human uses and reservoir evaporation. We use a three-year average to help smooth flows” over time, he said.

If approved and implemented, this system would set a fixed percentage of the river’s flow to be released, with upper and lower limits of the actual release amount. It would come in place of the proposals the states have been fighting over the last few years to spell out how much each basin would have to cut in water use.

That issue has tied the two sides up in knots, with the Upper Basin states saying they’ve already suffered too much for existing river water shortages and the Lower Basin states saying they don’t want to bear the entire burden of fixing the river’s longstanding deficit between water supply and demand.

“if this comes to fruition, the Upper Basin agrees to send a three-year average flow to us,” Buschatzke said. “They have an obligation to do so, however, they have to do it. If they have to cut that use, they do it that way. If they want to lower reservoirs, they do that.”

“We will not weigh in on how they do it,” Buschatzke told the Star.

‘Sets aside disputes’

When the Lower Basin states were seeking curbs in water use by Upper Basin states, the Upper Basin’s view was that they’ve already made those cuts by taking water out of some of their reservoirs, built under the 1956 law that approved creation of Glen Canyon Dam, Flaming Gorge dam and others, Buschatzke said.

“We in Arizona believe that under the law of the river, water in the Upper Basin reservoirs is there for the Upper Basin to meet their legal obligations to deliver a fixed minimum amount of water to meet Colorado River Compact compliance (rules),” he said. “Now, we’re not worrying about that.

“It sets aside disputes over details of what the Law of the River means,” said Buschatzke about the collection of laws, court rulings and regulations that govern the river’s management. “We would be willing to hold our compact compliance claims, as long as the Upper Basin was delivering the agreed-upon amount of water.

“We wouldn’t waive the claims. We would set them aside,” he said.

The seven states’ representatives have been discussing this idea privately for a couple of months, he said. The seven states and the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation will be preparing computer-based modeling to determine what the appropriate natural flow should be, he said.

“From our viewpoint, that flow has to take into account the sharing of hydrologic risk and under the background of the existing Law of the River,” he said.

“Sharing hydrologic risk means you want to make sure the Upper Basin has ... a somewhat commensurate risk with the Lower Basin. None of the numbers have been worked out.”

In a statement emailed to the Star, Becky Mitchell, Colorado River commissioner for the state of Colorado, was receptive to Buschatzke’s proposal, with some caveats.

“Colorado remains committed to developing supply-driven, sustainable operations of Lake Powell and Lake Mead, and the natural flow approach is one way to achieve this, if it is done right,” said Mitchell, who has been the most vocal Upper Basin water official during the Colorado River debate.

“Any approach must recognize uses across the system as defined in the Colorado River Compact, and provide a path towards equitable and sustainable uses across the system.”

Whatever is agreed on must protect the river system more effectively than the 2007 operating guidelines that the new rules are supposed to replace, she said. Those guidelines are widely seen as having failed in part because they didn’t do nearly enough to curb river water use as the river flows declined by nearly 20% from their 20th-century average of about 15 million acre-feet a year. An acre-foot will serve four Tucson households for a year.

“There is no doubt that Arizona views things differently than the Upper Division States, and a successful framework will set aside our differing views and focus instead on the health and sustainability of the Colorado River System for all who depend upon it,” Mitchell said in her statement.

“In recent years, operations at Lake Powell and Lake Mead have responded to poor hydrology with a short-term, crisis-to-crisis approach because the current operational guidelines are demand-driven, and therefore do not sufficiently protect Lake Powell and Lake Mead through dry hydrologic conditions,” said Mitchell.

“The post-2026 negotiations offer us an opportunity to move to a supply-driven approach, and for all across the system to adapt uses to the available supply. We collectively must live within the means of the river.”

She said this year on the river, when spring-summer runoff into Powell is predicted to be 45% of normal, is shaping up like 2021. That year, “the Upper Division States reduced uses by almost 1 million acre-feet to adapt to the limited available supply. Shortage in the Upper Basin results in real, painful, and uncompensated wet water cuts to farmers, tribes and other water users, using time-tested water rights administration based on the priority system.”

‘A huge change’

Fleck and Kuhn, who co-authored a book on how the Colorado River Compact’s water allocations to the states were based on inflated estimates of river flows, both praised the new proposal from Buschatzke.

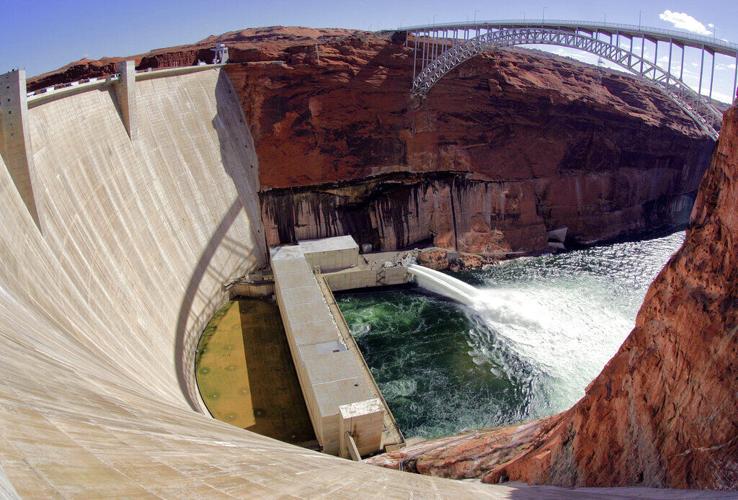

Glen Canyon Damon the Colorado River near Page, Arizona. Arizona’s water chief is proposing to tie future water releases from Lake Powell, through Glen Canyon Dam, to Lake Mead on how much water is actually in the river, rather than what forecasters predict will be there or century-old allocations said should be there.

“They are proposing to allocate water based on what’s available, not what they wish was available,” said Kuhn, a former general manager of the Colorado River Water Conservation District in Glenwood Springs. “That’s a huge change.”

The proposal also has the great virtue of each basin getting out of the other basin’s business, by using one clean, simple number, Fleck said. But establishing the right percentage remains the hard part.

“Make the percentage too high and the Upper Basin would have to cut users with (historic) ... water rights, something that has forcefully been asserted to me ... (that) the Upper Basin argues it has no ability to do. Make the percentage too low and Lake Powell fills up while Central Arizona goes dry.”

But some of the early computer modeling done for the proposal “suggests that there may be a sweet spot where a combination of Lower Basin cuts along the lines of what the Lower Basin has already been willing to offer, combined with modest Upper Basin system conservation programs, might thread a needle that could allow the crafting of a compromise,” Fleck said.

“This is very good news if the negotiators and the folks back home who have been egging them on can seize this opportunity to set aside parochial smallness and think at the basin scale.”

Behind the series: The Star's longtime environmental reporter Tony Davis shares what inspired him to write the investigative series "Colorado River reckoning: Not enough water."