Her baby couldn’t make it home for the holidays, but at least Dani Mendoza DellaGiustina had some out-of-this-world snapshots to keep herself warm.

DellaGiustina is principal investigator for NASA’s OSIRIS-APEX spacecraft, which is currently cruising through the inner solar system en route to a rendezvous with the asteroid Apophis in 2029.

This year was a busy one for the robotic space probe: In May alone, it survived its third close encounter with the sun and the temporary cancellation of its funding by the Trump administration. Then in late September, with its budget partially restored, the spacecraft used its University of Arizona-designed cameras to collect pictures of Earth — including a couple of selfies — as it swung by at a distance of about 2,100 miles.

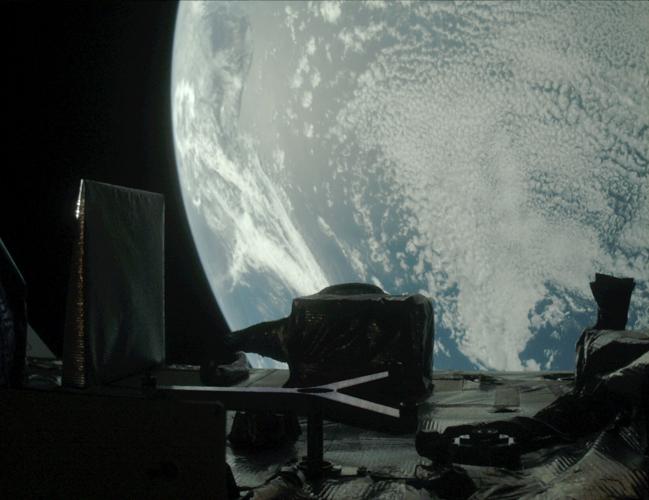

The StowCam on the Tucson-born OSIRIS-APEX spacecraft was designed to visually verify the safe storage of asteroid samples collected during the first part of robotic probe’s mission. But the camera is also good for taking “selfies” above the Earth, as evidenced by this shot from Sept. 23.

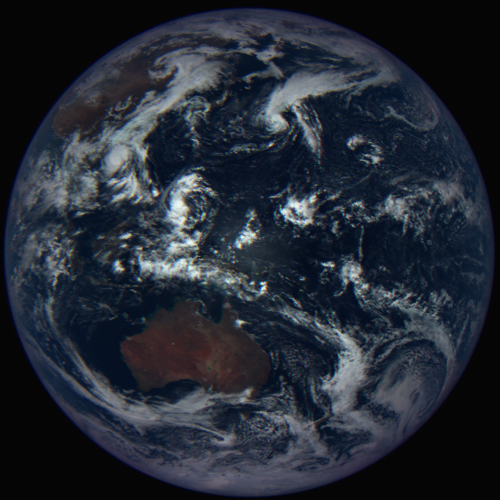

DellaGiustina's favorite is the photo NASA highlighted on its blog last month. “I hand-chose that one," said the assistant professor at the U of A’s Lunar and Planetary Laboratory. "It’s Earth as a blue marble filling the field of view of our MapCam imager.”

The composite image, showing Australia framed by swirling clouds over the Southern Hemisphere, was taken from a distance of about 142,000 miles, as the spacecraft accelerated away from its home planet once again.

Assistant professor and geophysicist Dani DellaGiustina poses for a photo with a wall sized mosaic of the asteroid Bennu, compiled from 2,155 images taken by the spacecraft OSIRIS-REx, inside the Kuiper Building at the University of Arizona. OSIRIS-REx has a new name, OSIRIS-APEX, a new leader in DellaGiustina, and a new mission to another asteroid, Apophis.

OSIRIS-APEX is mercifully short for Origins, Spectral Interpretation, Resource Identification, and Security-Apophis Explorer. It is a $200 million extension of NASA’s earlier OSIRIS-REX mission, also led by U of A researchers, that made history by briefly touching down on the asteroid Bennu in 2020 and returning samples from the space rock to Earth in 2023.

Since then, the spacecraft the size of a passenger van has been circling the sun in pursuit of its next target, under the guidance of a mission team that includes the U of A, NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, Lockheed Martin Space, KinetX Aerospace and the Canadian Space Agency.

The flyby of Earth on Sept. 23 was the first of three slingshot maneuvers planned over the next three years. “What our very clever flight dynamics engineers did is they found a way to use successive Earth gravity assists to get a little more energy and then a little more energy,” DellaGiustina said.

Those speed boosts will allow OSIRIS-APEX to finally catch up with Apophis about two months after the asteroid as big as the Empire State Building streaks past our planet on April 13, 2029, close enough to be visible at night over parts of Europe and Northern Africa.

The spacecraft will then enter orbit around Apophis to collect high-resolution images and spectral data, before swooping in close enough to stir the surface of the asteroid with its thrusters. DellaGiustina said they might even try jabbing at the rock with the probe’s sampling arm.

Stellar selfies

But first, she said, the mission must sweat through three more “close perihelion passages, where we get within the orbit of Venus,” roughly 25 million miles closer to the sun than the spacecraft was originally designed to operate.

“We need to configure the spacecraft in just the right way to withstand that really warm environment, and then we need to de-configure the spacecraft after we get out of those,” DellaGiustina explained.

Engineers call it “the fig leaf,” because it involves folding one of the two solar-panel wings in such a way that it shields the probe’s most sensitive bits.

NASA's recent selfies from OSIRIS-APEX were taken using StowCam, the aptly named camera originally used to visually verify safe storage of asteroid samples collected during the probe’s primary mission.

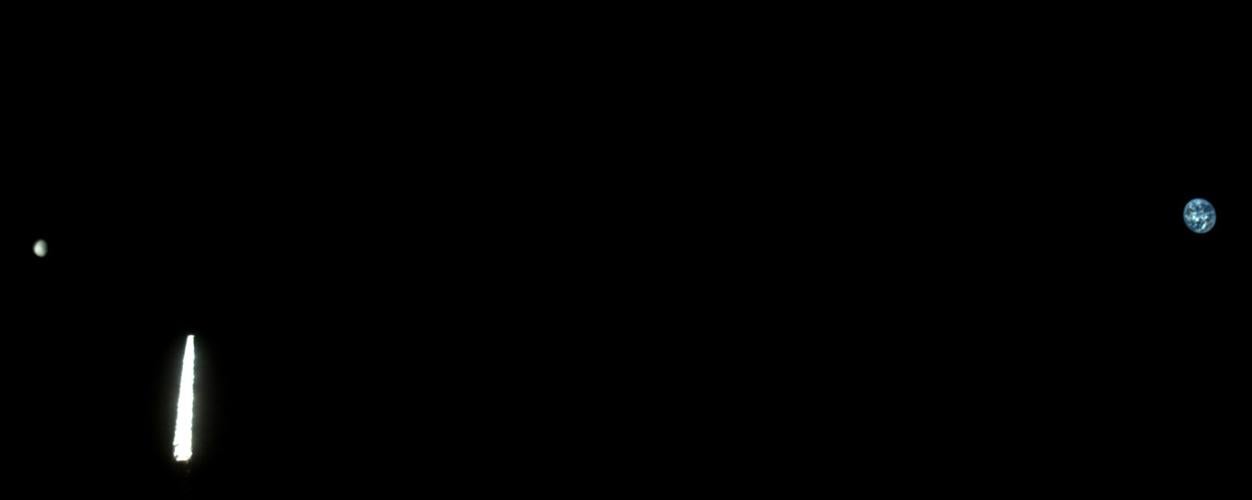

One StowCam shot shows our pale blue planet rotating beneath the spacecraft’s instrument deck. Another is a double exposure, taken from farther away, with a pea-sized moon on one side and a dime-sized Earth on the other.

A double-exposure shows the moon, left, and the Earth from about 37,000 miles away, as photographed by the StowCam on board the University of Arizona-run OSIRIS-APEX space probe during a close flyby in September. That’s light reflecting off the spacecraft in the foreground.

It’s not just about collecting cool pictures, DellaGiustina said. Passing close to Earth gives the science team something to train their instruments on in preparation for Apophis, allowing for crucial calibrations that should improve the quality of the data they collect once the probe reaches its final destination.

“It's great when something fills your field of view, like the moon or a cloud” on Earth, she said. “Honestly, the moon is an amazing calibration target, because unlike our Earth with the dynamic atmosphere, the moon is what it is. Its color, its brightness, its spectral properties aren't really changing.”

One thing DellaGiustina notices right away when she looks at the recent pictures of Earth is how much better they look than the ones the spacecraft captured in 2017, back when it was still known as OSIRIS-REx.

“I see the manifestation of a decade of using these instruments and really getting good at it. It represents just a huge amount of knowledge gained through years and years of practice,” she said. “That's part of the reason why these extended missions are such a good bargain: You go into (them), in some ways, more capable than you started for the prime mission.”

Budget blackhole

As recently as May 30, it looked like OSIRIS-APEX might be dead in space.

That’s when the White House Office of Management and Budget announced plans to cancel 19 other active space missions, including the journey to Apophis, as part of a roughly 50% cut to NASA’s science budget.

DellaGiustina called it “the least fun I have ever had at my job, hands down.”

The news hit shortly after classes got out at the U of A. So instead of science, DellaGiustina spent her summer break on “political advocacy” — namely, working with the university to communicate the importance of the ongoing mission to lawmakers on Capitol Hill, she said.

Luckily, they had a compelling case to make. The planetary defense implications alone seemed like enough to save OSIRIS-APEX.

If you want to be able to protect Earth from a killer asteroid like Apophis someday, you have to understand its composition and behavior. “You just can't learn about how these things respond to impulsive forces without going and poking them, so to speak,” DellaGiustina said.

A NASA animation shows the spacecraft now known as OSIRIS-APEX as it prepares to use its thrusters to stir the surface of asteroid Apophis in a maneuver scheduled for September of 2030.

It took several months and some key help from Republican Rep. Juan Ciscomani and Democratic Sen. Mark Kelly, but the mission’s funding was eventually restored, at least in part.

“The thing that I think really hit home for people on both sides of the aisle is that this sort of thing — an asteroid this large, getting so close to the Earth — only happens once every 7,500 years. And we have a billion-dollar asset that is already in space on its way to study that very, very rare event we are never going to get another opportunity to observe,” DellaGiustina said. “It seemed like we were able to convince people that this is worthwhile science to be done.”

She said the experience was a valuable reminder of the importance of communication for scientists like her. If they want taxpayers to continue footing the bill for their research, they have to be able to articulate why that work matters.

“This is part of my job,” DellaGiustina said. “I knew that before, but I really, really feel it in my bones now.”

One more mission

The OSIRIS-APEX team is expecting a lot less excitement in the new year. If everything goes according to plan, 2026 should be the quietest part of the mission’s so-called “cruise” period leading up to its arrival at Apophis. Outside of a few maneuvers to maintain the proper heading, the spacecraft will spend the next year traversing empty space, with no dramatic flybys of the sun or the Earth until 2027.

But the word cruise is a little misleading, DellaGiustina said, because "it gives the impression that we're just chilling." Even during down times, there is still plenty of work to be done.

“We find issues in our flight software from time to time that we need to correct,” she said. Those changes have to be computed, written, uploaded to the spacecraft and then tested.

The team is also busy writing code to recalibrate the scientific instruments in response to the tests conducted during the Earth flyby a few months ago. Mission scientists will need to figure out how to compensate for onboard sensors and camera lenses that might have gotten dirty during the probe’s contact with Bennu five years ago.

A coat of dust could actually turn out to be a good thing, DellaGiustina said. She compared it to putting on sunglasses to keep from being blinded by Apophis, which is thought to be almost 10 times brighter than Bennu.

“There's a filter in optics called a neutral density filter, and the dust kind of provides the same effect,” she said. “I mean, you can't make this stuff up, right?”

Australia can be seen in an image of the Earth as seen from the University of Arizona-led OSIRIS-APEX NASA space mission in late September. This photo was taken from about 142,000 miles away, after the robotic spacecraft had sling-shotted past the planet on its path to rendezvous with the asteroid Apophis in 2029.

The mission recently picked up some extra science work — and a little bit more money to pay for it — from NASA’s astrophysics division. OSIRIS-APEX is now collecting data about what the Earth looks like from a distance to help in the search for life elsewhere in the galaxy.

As researchers develop future missions to directly observe exoplanets beyond our own solar system, DellaGiustina said, they will need to know how to resolve those faraway worlds in different “geometries,” based on where the objects are and how they are being lit by their host stars.

“We have an opportunity to start observing the Earth in some of these unique geometries that you don't get unless you send a spacecraft pretty far from our own planet,” she said. “We're giving them a good dataset (of) what a habitable world looks like when you observe it under comparable conditions.”

A handful of earlier spacecraft have already sent back images of the distant Earth, perhaps none more famous than astronomer Carl Sagan's “Pale Blue Dot” photo captured in 1990 by Voyager 1 from more than 3.7 billion miles away.

But DellaGiustina said OSIRIS-APEX is taking things to a whole new level.

“Because we're transiting the inner solar system a few times, and we are doing this very thoughtfully and not necessarily serendipitously, we can really examine the Earth under a wide variety of astronomical viewing conditions, as well as the different wavelengths we can look in (for) those key spectral indicators of life,” she said.

The mission team began collecting the data in August, as the spacecraft raced toward its first gravity assist in September. More observations will be made during future flybys, starting with the next one in 2027.

“It's hard to get something into space with these fantastic instruments, so it's great to maximize its use and learn as much as possible,” DellaGiustina said.

OSIRIS-APEX’s recent images of Earth are the perfect example of that — something gained by continuing to explore.

“It feels a little triumphant to see those” pictures, she said. “Beautiful data acquired through lots of lessons learned, and we're still still kicking.”