It's just another dirt lot in one of Tucson's older neighborhoods.

People park cars there occasionally, to go to nearby Davis Bilingual Elementary Magnet School, or to Oury Recreation Center. The patch of land collects the usual desert debris when the wind blows.

Arizona Daily Star columnist Tim Steller

Now it also serves as a symbol of the challenges the city of Tucson and developers may face as they try to build the local housing stock and keep prices within reach for locals. City officials foresee the need for 35,000 units of additional housing in the next 10 years and are pushing to get units built on city-owned land.

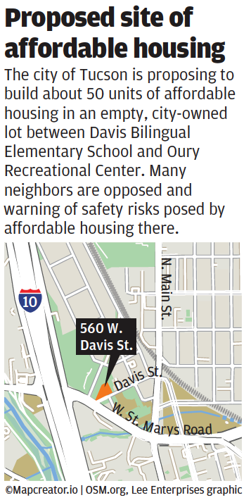

The city owns that 1.73-acre lot in Barrio Anita, a small neighborhood north of downtown. But in 2019, they promised the neighbors that they would turn it into a parking lot with green infrastructure, like trees and stormwater basins. Now the city wants to put affordable housing there — about 50 townhomes.

That has some neighbors pushing back, reflecting a pattern that is familiar around Tucson wherever new housing or other changes are proposed. In the same areas where residents have long fought so-called "gentrification" — soaring housing prices as outsiders move in, sometimes displacing longtime residents — they also have viewed city-proposed affordable housing with suspicion, although it intends to limit prices.

Barrio Anita Neighborhood Association President Gracie Soto has helped lead opposition to the housing plan, raising fears that the affordable housing there could bring safety issues to the school and park.

"They're not talking about the safety," she said in an interview Thursday. "They're talking about the colors and the way it's going to look in the models. But it's like, what about the safety?"

Soto was even allowed to bring that concern to a student assembly at Davis school in October. Rene Bernal-Mejia was one of a small number of parents also in the all-school assembly when Soto got the microphone and painted a scary picture of the proposed housing in the lot next door.

"I was wondering why she was saying it was dangerous and not good for the city," Bernal-Mejia said. "I’m like, 'Why are you trying to scare kids with this nonsense about dangerousness?' I think she was trying to direct it toward parents and teachers, but students also heard it."

Affordable housing championed

New housing could hardly have a stronger booster than the City Council member who represents Ward 1, the west-side district that Barrio Anita is in. When I interviewed her Thursday, Vice Mayor Lane Santa Cruz was wearing a T-shirt with the slogan "Legalize housing" across the front.

"I want any city-owned property in Ward 1 to be prioritized for affordable housing," she said.

That includes not just the Barrio Anita property, but also land in Menlo Park, Barrio Sin Nombre and Barrio Santa Rita Park-West Ochoa, among other places.

To an extent, Santa Cruz's predecessor in Ward 1, Mayor Regina Romero, stuck her with the Barrio Anita conflict. Romero was running for the Democratic nomination for mayor on July 1, 2019, when she sent a letter to then-City Manager Mike Ortega saying she would like the property to be a parking lot, at least temporarily. It would cost the city a couple of hundred thousand dollars to build up the green infrastructure and make the lot what residents wanted.

The city plans to develop a multi-family housing project on an empty city-owned parcel of land between North Main Avenue and West Davis Street, in Barrio Anita on Tucson's west side.

"When I came into office I was kind of frustrated," Santa Cruz said of her predecessor. "I'm like, 'Why are you making that commitment as you're on your way out?' But when I came in, I was like, I do not want to spend that kind of money on a parking lot."

Instead, she and city housing officials, through their El Pueblo Housing Development arm, are seeking federal low-income housing tax credits and a developer as a partner to build on the site. An additional, smaller site, across the street at 450 N. Main Ave., would be part of the federal proposal and host 17 units of housing.

Last week, Mayor Romero revised her 2019 position in a new letter about the Barrio Anita site: "While this lot has served as temporary parking, I now support moving forward with this housing development. At a time when thousands of Tucson families are struggling to find an affordable place to live, leaving this land underused is simply not an option."

And while they have encountered some significant pushback from the residents of the small neighborhood between the railroad tracks and Interstate 10, they've also found some support at the school.

"I’m actually really excited about the idea that there wil be affordable housing in Barrio Anita," said Brieanne Buttner, a member of the Davis school PTA and site council. She foresees the area being "more accessible to working class and middle class families that have been marginalized from that housing."

Suspicion of housing proposals

It's not just Barrio Anita where city housing proposals have met with suspicion. A large plot of land next to the Caterpillar office, known as the Nearmont site, has raised some fears that too much housing will be placed in the tiny neighborhood, Barrio Sin Nombre, south of the Mercado District.

In Barrio Santa Rita Park-West Ochoa, the city is planning hundreds of possible apartment units in a large parcel across South 10th Avenue from Southside Presbyterian Church. Brian Flagg, who is vice president of that neighborhood association, has campaigned ceaselessly against housing unaffordability in neighboring South Tucson, where he is on the city council. But he is suspicious of the city's plans in the Tucson neighborhood.

"God knows we need housing, but we don’t need housing that would alter the makeup of the neighborhood drastically," Flagg said. "'Affordable' has got to be really well defined, or it will be used against you."

Indeed, in both Barrio Anita and Flagg's neighborhood, residents have likened the city's attempt to create affordable housing to "gentrification" or even "urban renewal" — the hated concept behind the destruction of much of Barrio Viejo in the 1970s.

But those are confusing ideas to apply to projects intended to make increasingly unaffordable neighborhoods more affordable.

"For me, it's just fear of change," Santa Cruz said. "It's pretty consistent. Anytime there's gonna be a housing development, people are like, 'We're gonna have more crime, we're gonna have more traffic.'"

Slow, limited housing ineffective

For some residents who resist new housing, the issue isn't housing in general, but density. That's the case in Barrio Santa Rita Park-West Ochoa, where the city has proposed 300 or so apartments. It's the case in Barrio Sin Nombre, and it's the case in Barrio Anita.

In nearby Menlo Park, just west of downtown, neighbors talked the city down from the idea of apartments on city-owned property along North Westmoreland Avenue. Townhomes are the current plan.

"As the Menlo Park neighborhood president who’s lived here for 15 years, I've watched housing prices skyrocket, and people being pushed out," said Kylie Walzak of that neighborhood association. "We are actively encouraging the city to develop affordable housing on there as fast possible."

But of course, fast isn't always possible, even when neighbors agree. And sometimes neighbors' terms are so limiting that the allowed projects won't make much of a dent. In Barrio Anita, Gracie Soto pointed out, the Pima County Community Land Trust is building six affordable homes intended for older people.

"They did their due diligence for what fits in our neighborhood," Soto said. "Anita already has affordable housing."

But what the city is recognizing in these efforts is that all these neighborhoods — the whole city — needs much more. I get why people are suspicious of the city, but it strikes me as unfair for those who own homes to insist that change be so slow and limited that it will have no impact on the problem at all.