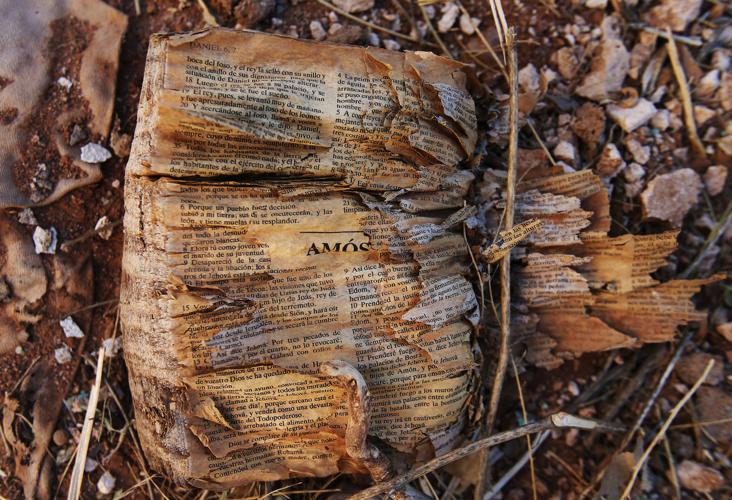

LAS CHEPAS, Chihuahua, Mexico — Sun streams through dozens of caved-in roofs in Las Chepas, scorching the abandoned shingles and backpacks strewn among rotting mattresses and cracked toilets.

The town, a stone’s throw south of the steel rail-and-post fence that separates Chihuahua, Mexico, from New Mexico, has seen better days. In the past half-century, Las Chepas passed from thriving farming community to illegal immigration staging ground to what it is today: a few residents eking out an existence.

Epifanio Ruiz, 53, one of about 40 people still here, recalls the 1980s, when the town had 500 people, many of whom crossed a barbed-wire fence daily to work on a farm just north of the border.

“At that time, the surveillance was nothing,” Ruiz says. “It was as if it was one country — Mexico and the United States.”

But changes in U.S. immigration law in the 1980s allowed local residents to gain legal status here and, rather than work on the nearby farm, they headed farther north to seek their fortune.

In their wake, migrants started showing up on their way to the United States, spawning a cottage industry of selling them food and supplies.

As the town became the hot spot for crossing the New Mexico border, James Johnson, 40, owner of the farm just north of town, saw buses drop off hundreds of people who were led by human smugglers, or “coyotes,” across his fields of onions, chile peppers, cotton and wheat every day.

“The buses literally were on, like, a 15-minute schedule,” Johnson says. Because of the empty buildings left by former residents, “it became an easy spot to collect all these groups and all these people. Coyotes would have them dropped here and they would cross at night.”

Would-be border crossers head east toward Puerto Palomas, Chihuahua, in 2006. “They will find a way, if they need jobs, to get here,” Rep. Jim Kolbe, R-Ariz. said then.

Illegal crossings were so frequent in the mid-2000s that the governor of New Mexico asked his counterpart in Chihuahua to demolish the empty buildings used as a staging ground.

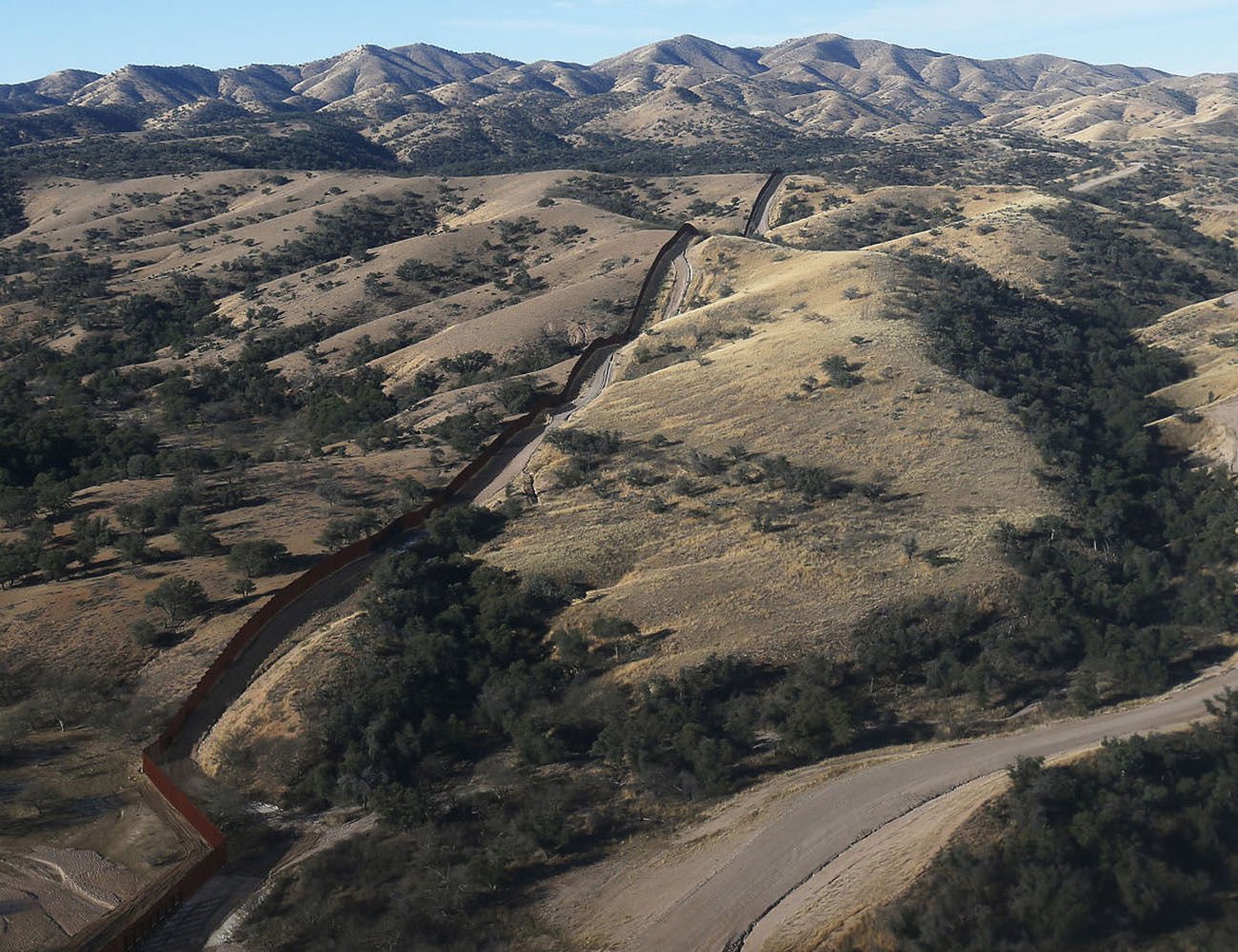

Around that time, Congress decided to invest billions of dollars in border enforcement. A steel vehicular barrier went up along the border and more Border Patrol agents arrived.

“When they put the fence up there on the line and more agents, there wasn’t a chance for people to cross anymore,” Ruiz says. “It was very closely watched and the people stopped coming.”

The Johnsons used to see about 700 people cross their land every day, but now, as Johnson says, “rarely do I see an illegal alien today.

“In 10 years, at least in our area, things have gotten a whole lot better,” he says.

The story of Las Chepas illustrates the pattern of recent migration: Faced with hundreds more agents, new fences, more surveillance technology and prison terms for illegally re-entering the United States, many migrants choose to cross elsewhere.

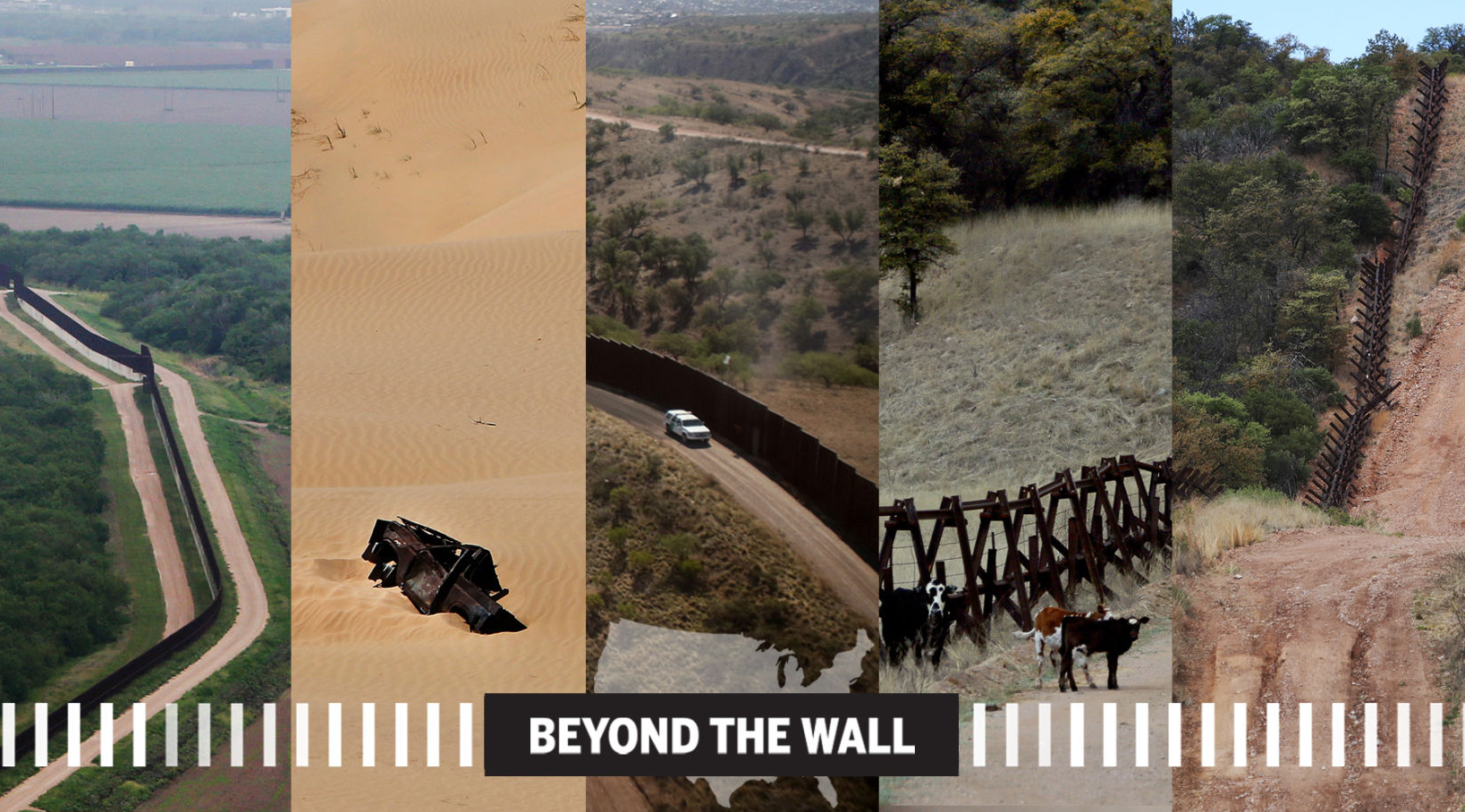

THE NEW MEXICO BORDER: EL PASO SECTOR

A U.S. Customs and Border Protection helicopter north of Las Chepas, Chihuahua.

• 179.5 total border miles

• 14.3 pedestrian fence miles

• 101.3 vehicle barrier miles

• 36 percent unfenced

• Tall fences cut through border towns, but much of the mountainous boot heel is separated from Mexico by barbed wire.

• Apprehensions fell by nearly 90 percent in the last decade, and seizures of marijuana dropped by more than half.

• The Antelope Wells Port of Entry in New Mexico is one of the last busy ports of entry, with about 30 vehicle crossings daily.

INTERACTIVE MAP OF NEW MEXICO-MEXICO BORDER

RED LINE = FENCED AREAS

Drag to move along the border. Tap dots to learn more about key spots along the way.

Drugs still flow

The roughly 1,600 residents of Columbus, about 15 miles east of Las Chepas, also used to see migrants coming across the border regularly, says Columbus resident Danny Garcia, 84.

Garcia ran a motel where, most days, 60 or 70 illegal immigrants would “sit there waiting for somebody to come and pick them up” and take them to “New York and all over,” he says.

“They claim that the murderers and rapists come from Mexico,” he says. “Hell, that ain’t true.”

A few minutes before Ruiz recounts the history of this place, a U.S. Customs and Border Protection helicopter hovers a few hundred yards north of the border while a Border Patrol truck barrels down the service road that runs along the fence, with the scene unfolding under the watch of a surveillance blimp. A few miles to the west, agents watch camera monitors inside Camp Ramsey, one of several forward-operating bases along the border in New Mexico.

Epifanio Ruiz, 53, stands outside his home in the small border village of Las Chepas, Chihuahua. Mike Christy / Arizona Daily Star

From 2006 to 2015, Border Patrol apprehensions in the El Paso Sector, which includes 180 miles of border in New Mexico, dropped from 122,000 to about 14,500.

“We saw a big decrease in 2007 and it just continued,” says Border Patrol agent Lorena Apodaca.

But the border in New Mexico is not completely closed off to illegal traffic. Drug smuggling continues in the El Paso Sector, where the Border Patrol seized 60,000 pounds of marijuana — although that’s down from 140,000 in 2006 — and 175 pounds of cocaine in 2015.

Las Chepas was the busiest section of the New Mexico border around 2008, but when crossing there was basically shut down, some of that migration shifted to Santa Teresa, a border town of 4,000 people about 60 miles east of Columbus.

And the new waves of migrants are different. Since October, Border Patrol statistics show agents have encountered nearly 2,000 minors traveling alone in the El Paso Sector, an increase of 173 percent compared with the same period last year. Another 2,300 people were detained while traveling as a family, a sixfold increase.

Many of the minors are Central Americans who turn themselves in to agents and ask for asylum, says agent Joe Reyes. They pay smugglers to get them to the fence, not realizing that if they are going to turn themselves in, it is much less costly to simply walk up to the port of entry.

The remains of a couch at a house in Las Chepas. Empty buildings like this were used as staging sites for groups trying to cross the border. Mike Christy / Arizona Daily Star

Ranchers shaken

While vehicular barriers run along the border and pedestrian fences do the job in Columbus and Santa Teresa, the border infrastructure in New Mexico’s boot heel is a different story.

In urban areas, pedestrian fencing plays the critical role of giving agents a few seconds before border crossers disappear into the local population. But in sparsely populated areas, crossing the border is just the beginning of a days-long trek.

A barbed-wire fence and mountain ranges separate the roughly 30-mile eastern flank of the boot heel’s windswept plains from Chihuahua. At the southern extreme of the state, barbed wire runs alongside a Normandy-style vehicle barrier. The western edge runs along the state line with Arizona.

For smugglers and migrants in southern New Mexico, the name of the game is Interstate 10, the area’s major east-west highway, which offers a quick getaway.

Agents track footprints, threads of burlap sacks caught in bushes and other “signs” left by border crossers as they head to I-10, border agent Apodaca says. They also watch for “drive throughs,” in which smugglers drive vehicles loaded with migrants or contraband through gates in the barbed-wire fence, often closing them politely behind them.

The mountains act as a natural barrier to border crossings, Apodaca says. And the vehicle barriers and heavy monitoring of Route 81 — the only major north-south road along the state’s southern edge — are more effective than a costlier pedestrian fence, she says.

Instead, “we are the barrier,” she says.

Farmer James Johnson talks about the migrant staging village of Las Chepas just across the border at his Carzalia Valley Produce farms, west of Columbus.

Catching illegal border crossers as they make their way north, rather than at the border itself, worries area ranchers, says Caren Cowan, executive director of the New Mexico Cattle Growers’ Association.

Fewer people are crossing there in search of work, but ranchers are seeing more drug traffickers — many of them armed, she says.

In December, a ranch worker was kidnapped and thrown into a vehicle loaded with drugs in the Animas Valley, north of the border. The kidnappers took him along I-10 to Willcox, Arizona. He was found alive, but the incident caused widespread concern among ranchers.

Besides the kidnapping, “there are multiple break-ins down there all the time,” Cowan says. “People down there feel like they’re in no-man’s-land.”

EXPLORE OTHER STATES

CALIFORNIA

CALIFORNIA ARIZONA

ARIZONA TEXAS

TEXAS