SAN LUIS RIO COLORADO, SON. — The shelter for deportees is a 10-minute walk from the U.S.-Mexico border.

But the shelter’s ledger shows that people staying here who plan to cross into the United States again don’t intend to do it here. Time and time again, their destination is 150 miles to the west, in Tijuana.

“They barely cross here anymore,” says Olga Escalante, assistant manager of the Casa del Migrante la Divina Providencia shelter.

Most of those who do are Central American families turning themselves in.

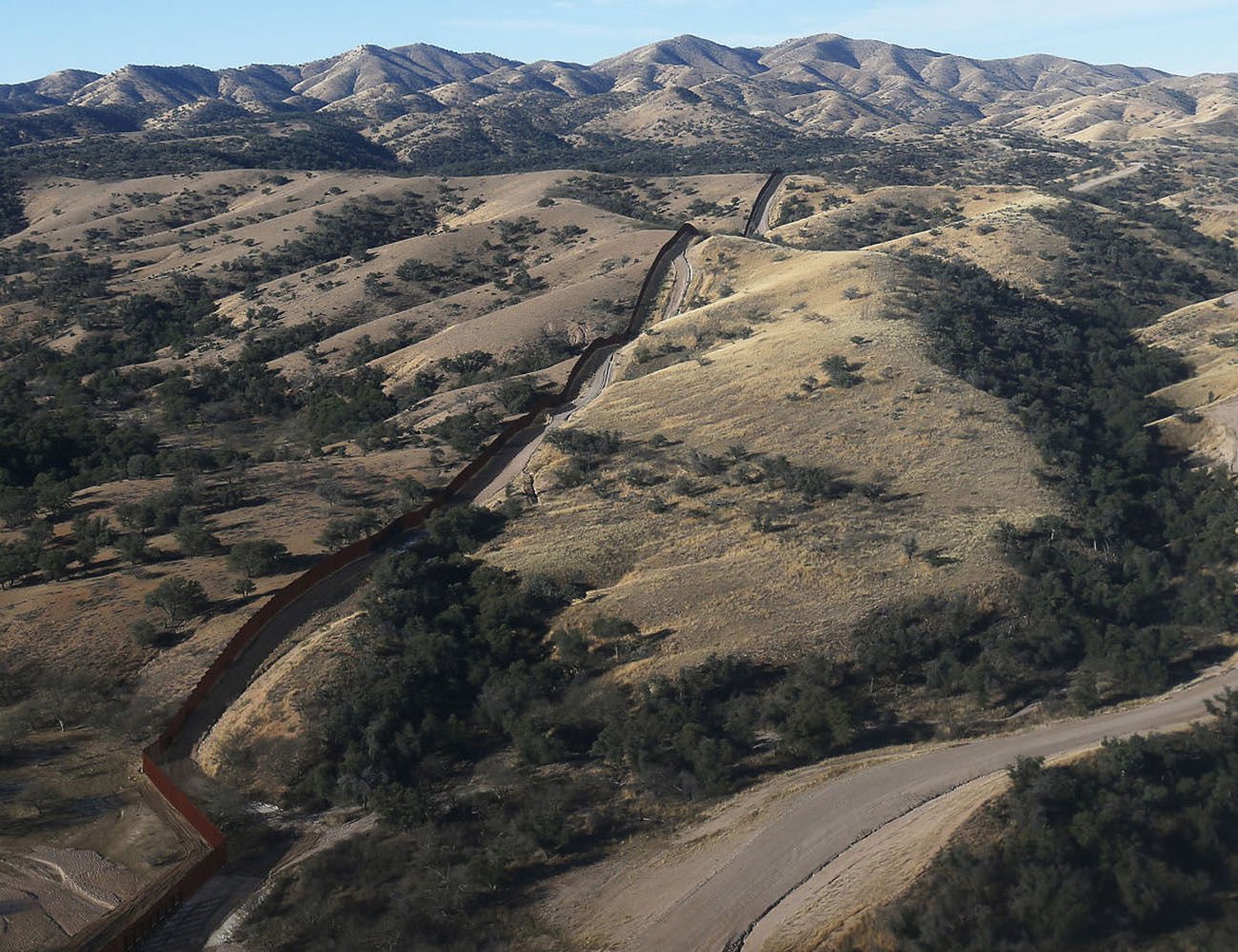

The Yuma Sector is the gold standard of border enforcement, thanks largely to 35 miles of fencing that runs along the Colorado River and heads west through the Imperial Sand Dunes — places the Border Patrol said in 2006 were too difficult to fence. To the east, the fence runs through the desert until it hits the mountains.

Downtown San Luis, Arizona, is a fortress, with eight miles of triple-layered fencing and nearly two miles of stadium lighting between the first two layers. The Yuma Sector’s 800 Border Patrol agents are stationed throughout the enforcement zone and are ever-present on the streets of San Luis and the other towns in the sector.

Escalante and several migrants at the shelter say the triple-layer fencing, the use of surveillance technology, and prison sentences for illegal re-entry in the Yuma Sector make San Luis an inhospitable crossing point.

Ubaldo Gutierrez, 39, has just been deported and doesn’t like his chances crossing the border there.

“The wall is taller, more surveillance, drones going around watching everything, helicopters, agents everywhere. It’s very difficult,” Gutierrez says.

Another man at the shelter, Eduardo Lucas, 23, is headed to Tijuana after being deported to try to get back to his family in San Diego.

Lucas’ parents brought him to San Diego from Michoacán, Mexico when he was 7 years old. After graduating from high school, he went to work as a cook in local restaurants.

But a DUI, followed by what he called fraud on the part of his lawyer, led to his deportation in early April through San Luis.

“Here, it’s difficult, and if they catch you they give you time” behind bars, Lucas says. As part of the stepped-up enforcement regime, the Yuma Sector was one of the first border areas to adopt Operation Streamline, a federal program that criminally prosecutes for illegal entry.

With the threat of prison looming in San Luis, he figures he has a better chance of avoiding prison by crossing the border in southern California.

“My family’s there so I have to try again,” he says. “I don’t know anything here, I left when I was really small. Everything’s new.”

Much of the increased enforcement effort in the Yuma Sector began in 2005, with 138,500 apprehensions, giving the sector one of the highest rates along the U.S.-Mexico border. After building more fencing, adding agents and implementing a strict prosecution program, apprehensions fell to 7,000 in 2015.

Escalante has seen a rise in people like Lucas who were arrested in California and deported through San Luis.

The Border Patrol’s San Diego Sector deports some Mexican nationals detained there through San Luis under the Alien Transfer Exit Program, agency spokesman John Lawson says. The program is meant to break up smuggling networks by deporting people far from where they were detained.

With the rise in border enforcement and deportations, the shelter in San Luis, Sonora, regularly fills up with deportees, as well as some northbound migrants from southern Mexico and Central America.

The ledger Escalante maintains at the shelter shows the number of migrants who stayed there more than doubled from 13,000 in 2006 to 27,000 in 2013. Last year it dipped to 21,000.

Despite the seemingly insurmountable difficulty, people still cross the triple-layered border fence, climbing a ladder or sometimes scaling the fence with grappling hooks.

Migrants, most of them deported, take coffee and breakfast at the Casa Divina Providencia migrant shelter in San Luis Rio Colorado.

And drug traffickers still see San Luis and the Yuma Sector as a smuggling corridor. While illegal migration fell precipitously, the amount of marijuana agents seized actually rose in the past decade, from 46,000 pounds in 2006 to 53,000 pounds in fiscal year 2015. Agents also seized 643 pounds of methamphetamine last year — most hard drugs are seized at legal crossing points.

Drug smugglers try to get around the fences by digging tunnels, including one that popped up under a store in downtown San Luis, Arizona, in 2012. They also fly ultralight aircraft over the border or shoot packets of drugs over the fence with a cannon. In April, the Border Patrol saw so many drug-smuggling drones in the Yuma area that it issued a public advisory.

As fewer Mexicans tried to cross the border illegally, more came from Honduras, Nicaragua and other Central American countries.

In 2006, nearly all apprehensions in the Yuma Sector were of Mexican nationals. By 2015, about half the apprehensions were of people from countries other than Mexico, mostly from Central America.

Recently, the number of people detained with family members has skyrocketed. Since October, agents in the Yuma Sector detained 2,900 people traveling as a family, a sixfold increase from the same period in fiscal year 2015. Unaccompanied children detained by agents nearly quintupled from 363 to more than 1,700.

In the most common scenario, agents encounter Central American families at the primary fence, where they turn themselves in, says Border Patrol agent Richard Withers.

Escalante says most people who come through her migrant shelter are searching for a way to stay with their families.

Joshua Guerrero, 11, peers through the U.S.-Mexico pedestrian fence with a homemade periscope in the northwestern Sonora town of San Luis Rio Colorado.

“They left their families and they can’t get back. Of course, they’re going to try, right?” she asks.

People at the shelter tell her about violence and a lack of jobs where they come from.

“It’s very painful for them. You see a lot of sadness here,” she says.

Gutierrez was deported to San Luis in early April. After leaving his native Guanajuato, Mexico, he spent 15 years in Stockton, California, with his family, working in the nearby produce fields.

He says he ran into trouble when he tried to get his immigration papers in order. As a result, he was told he had to leave the United States for 10 years.

“My family is up in California suffering,” he says. “I want to get home to help them, but I can’t.”

Gutierrez doesn’t have any money left to pay a coyote, so he is looking for a way to cross the border on his own.

In the meantime, he says he is going to find a job in Mexico. But that doesn’t mean he’s giving up on returning to the United States.

“What you make in one day there,” he says, “you don’t make in a week here.”

Beyond The Wall

Arizona: Border fence cuts Tohono O'odham Nation in half

'After 9/11 this is what we got,' tribal member says of increased Border Patrol agents, electronic surveillance on the border-spanning reservation.

Slice of border life

Arizona: Generations on both sides learned English at Agua Prieta kindergarten

Families here live on one side of the line, work and shop on the other.

Slice of border life

Arizona: Playing ball by the wall

Boys' ball game inadvertently becomes international incident.EXPLORE BY STATE

CALIFORNIA

CALIFORNIA ARIZONA

ARIZONA NEW MEXICO

NEW MEXICO TEXAS

TEXAS