When De Anne Dwight got the news about her presidential pardon in January, she was also told not to tell anyone.

This after a 28-page application, a document hunt for decades-old papers, an FBI interview and months of waiting as the end of Barack Obama's presidency ticked nearer and nearer.

Finally, she got the call.

Wait until after the press conference, she was told the day after Martin Luther King Jr. Day. Then you can tell.

So she put on some makeup, donned a huge smile and began her shift as a registered nurse at Banner-University Medical Center.

People wondered why she was so happy.

Oh, it's just a good day, she told them. A very good day.

"I'm always smiling with my cute little makeup," Dwight, 47, says. "People would never believe I have a mug shot."

But after about 17 years of sobriety, she feels like she has lived two lives. She devotes this life, her second chance, to giving other addicts hope for a future. That's what this pardon is all about for her — to show others that recovery can happen, to show them it does happen.

A presidential pardon doesn't erase the past or imply innocence. But it does remove the civil limitations that can follow a conviction and indicate the president's forgiveness and his recognition of a life turned around and responsibility taken.

Dwight's first life came sputtering to a halt on the cement floor of a holding cell on the Mexican side of the border. It was June 1999 and she was under arrest with two life sentences headed her way: One for possession with intent to distribute and the other for the importation of a controlled substance.

Dwight got caught smuggling crystal meth across the border — not to share, not to sell. It was all for her, she says.

There was a moment before her trip to Mexico when she contemplated visiting a nearby casino instead of crossing the border.

"That could have been a turning point to make the right decision," she says. "But I didn't. I kept going."

She remembers sitting in a holding cell in Yuma later, surrounded by other girls, newly booked or court-bound.

"I'm listening to these girls talk like, 'I'll trade you some Oodles of Noodles for some mascara,' and I'm like, 'This cannot be my life. Oodles of Noodles and mascara?'" Dwight says. "I remember one girl talking about killing her brother and for the first time in all of this ... I was scared."

The end of innocence

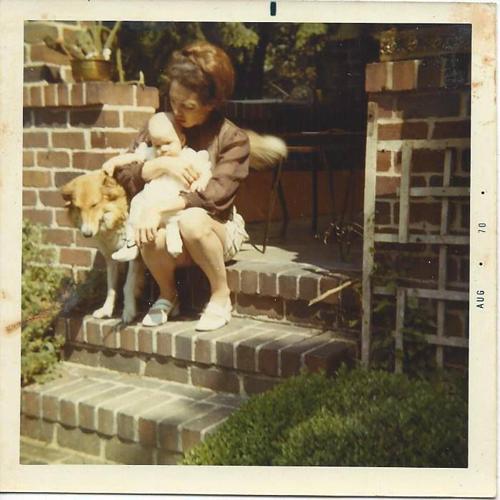

Dwight's grandparents raised her in Baltimore — her parents divorced when she was 2. Her mom, a nurse, was there but busy. Her dad was basically an alcoholic, she says, and she saw little of him.

De Anne Dwight with her mother.

She remembers going to Alcoholics Anonymous meetings with her grandfather, too young to know what was going on. She liked the cookies and juice. Her grandmother spoiled her in typical grandmother fashion.

The year she turned 10, her life changed. Her mother died suddenly. Her father became a quadriplegic in a separate accident.

When she was 12, her grandmother had her first seizure. Dwight threw herself into sports and school. Those were her friends — sporty kids, smarty kids.

Everything changed when she attended a party with a different crowd — older kids, some not even in school.

"It seemed innocent at the time: Put everything you can find in your grandparents' liquor cabinet and put it in a Tupperware and bring it to a party," she recalls.

Dwight had her first drink there and got sick. She was raped at that party.

She was 12.

"I went to this other party the same day, where I was really supposed to be..." she says. "And I went to that party and they were playing spin the bottle. I remember sitting on the steps looking down into the basement thinking I could never play that innocent game again."

Looking for love, looking for drugs

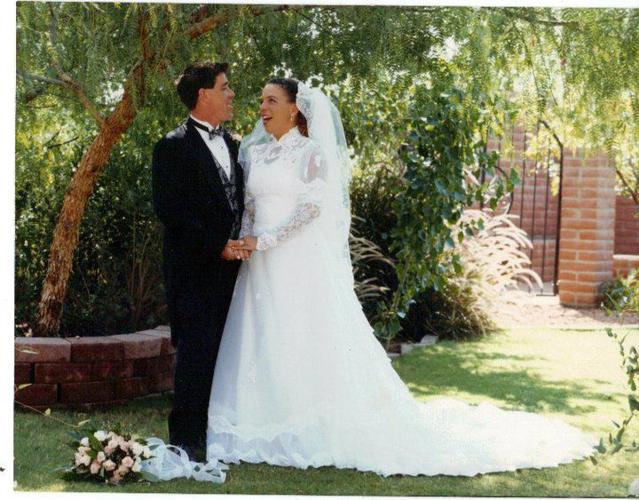

Sitting in the kitchen of her midtown home, sun streaming through a window, Dwight marvels about her 17-year marriage to Jeff Dwight. Every five years, the couple renews their vows.

"I would never have guessed in a million years that I would be faithful to one man and love him, you know?" she says. "That's a big deal."

Jeff and De Anne Dwight have been married since 2000.

That's because that first party launched her into years of addiction to alcohol, drugs and relationships.

As a 17-year-old, she ran away and was later emancipated, drinking and partying through her last year of high school.

"I ran away to the beach because you could have bonfires and beach parties every day, and I thought, 'Oh perfect,'" she says.

There, she began a relationship with an older man, with whom she started doing cocaine.

"That whole summer was older men, new drugs and independence," she says. "Pretty much the first time we were together, he was abusive. We ran out of drugs and he tied me up and put a knife to my neck and said, 'You better be here when I come back.'"

Despite the abuse, Dwight stayed, moving from place to place, hoping a new location would improve the relationship.

"No matter where we went, we drank, got drunk, got into arguments, and he would be abusive," she says.

At some point, crystal meth entered the picture.

When the couple moved to Florida, Dwight, 25, ran to a women's shelter.

"I wanted to join the Merchant Marines, because my grandmother always talked about the Merchant Marines, but I couldn't find their number in the phone book," Dwight says. "So I called the Marine Corps and said, 'Do you guys have the number for the Merchant Marines?' They said, 'No, but if you come down here, we'll help you find it.' ... Literally, I was in boot camp three days later."

"Someday this might save your life"

Dwight loved the Marine Corps.

She graduated boot camp at the top of her class, was expert with a rifle and was going to be an air traffic controller, she says.

"It was the first time I felt like I belonged, like I had a purpose," she says. "I felt safe at the time away from him."

The Marine Corps taught her lessons that would later apply to her recovery.

In the Marine Corps, De Anne Dwight found purpose.

"In the Marine Corps, you get up and make your bed. Unmake your bed. Polish your boots. Polish your gun. Take your gun apart. Put your gun back together," she says. "I remember in boot camp you walked around the island for three days. Why did we do that? Because somebody told you to. And someday it might save your life."

It's the same thing she tells recovering addicts.

"Read the book. Call a friend. Go to a meeting," she says. "Why? Because I said so. Because one day it might save your life."

The Marine Corps stationed her in Memphis, and the man she had escaped found her. She gave him another chance and married him.

When the Marine Corps stationed Dwight in Yuma, her life began unraveling again. Her husband got back into drugs and in one instance beat her so hard he ruptured her spleen, she says. The Marine Corps flew her the Naval Medical Center in San Diego, where she lied, telling different doctors different causes for the injury. She still has the scar from the surgeries that stretches up and down her torso.

Dwight says her Marine Corps career fell apart when her husband drugged her drink at a party. The Marine Corps wouldn't tolerate drug use.

"It was horrible getting kicked out," she says. "I wanted more than anything to stay. I always tell people the Marine Corps is what saves my life literally today."

Crossing the line

The end of Dwight's career as a Marine also brought an end to her marriage.

She ended up with a job at a radio station, hosting a morning show.

"I had a purpose again," she says. "But still it was, let's drink and party, because that's the life, but don't be crazy with drugs, because I got rid of the crazy guy."

Men bounced in and out of her life. And then so did crystal meth.

"But this time it was different," she says. "It was like I couldn't stop doing it. There wasn't enough to keep me high enough."

She stopped partying, stopped going to bars for any reason but to restock her drug stash. She became frustrated with waiting for someone else to supply her the drug. After years under the thumb of her ex-husband, she wanted to be in control.

Mexico, she learned, was the answer.

"I never even thought about being in a dangerous position," she says. "That's what's so stupid. I don't know these people. I don't know what they're giving me. It never even mattered. I literally wasn't even in touch with reality."

She stopped sleeping and lost her car. She stopped showing up to work.

Dwight remembers sitting in her closet during a party at her apartment, exhausted.

"God, I'm tired," she said.

She hadn't thought about God since the day she stood in church looking at a flag draped over her mother's coffin.

"I hadn't thought about God at all in the picture," she says. "And then I joke that two days later, I was resting on the floor of a holding cell in Mexico."

The next right thing

When law enforcement stopped Dwight at the border, searched her and discovered the drugs, they locked her up on the Mexican side of the border, she says.

It almost came as a relief to Dwight, now 29, who guesses that she was awake for around 11 days on her last high. She crashed on the cement floor.

"Nowhere in my mind did I think, 'What if Mexico keeps me? That would really suck,'" she says. I probably wouldn't be here today, telling my story ... I was totally unrealistic."

She was transported and incarcerated in Yuma's county jail before getting moved to federal prison.

"They put me back in those same clothes again," she says, referring to what she was wearing when arrested. "When I tell my AA story or my 12-Step story, I always say that must be what it feels like to relapse, because relapsing is not part of my recovery. ... The only thing I can relate to is going back to those same dirty clothes over and over again."

At the now-closed Vida Serena rehabilitation center in Tucson, her life began anew.

"In treatment is where I started living and learning life lessons like you have to be flexible," she says. "It doesn't matter what one person says, is it the right thing to do? Is it the rule?"

She still struggled with her desire to drink and use, thinking that there was a "normal" way to do both.

"Nowhere was I remembering that I was facing two life sentences," she says. "The one charge was on possession with intent, and the other charge was for the importation of a deadly substance."

At one hearing, the judge dropped the first sentence. At another, the judge ordered her back to rehab for three months.

In treatment, she started going to meetings and learning about herself. She learned about her fears and her issues with anger. A woman became her sponsor, someone who would help her through the 12-Step program. Dwight started going to church.

She began doing the next right thing and the next right thing and the next right thing. Just like in the Marine Corps.

"People forget it's that simple," she says. "They are so worried about the steps and worried about what they have to do on the ninth step that they don't take time to do the first one: Just don't drink. Just don't do drugs."

A judge sentenced her to time served plus five years of supervised release. That meant the two weeks she spent in jail and the year and seven days she spent in treatment counted as her sentence. That was it.

"When I look back on it, it makes me cry," Dwight says. "I busted my butt to do the right thing no matter what anybody else was doing."

Relapsing was not an option

The Dwights own a home in an area that De Anne Dwight describes as "drug central." People know that at the Dwights, they can find help.

"I just hate that people relapse," she says. "They keep putting themselves in that situation when there's hope and there's help."

Dwight never allowed herself to relapse. When it became tempting those first few months of treatment, she would go outside and walk what she calls her "prison circle" — a space about the size of a jail cell. In those days she repeated her mantra: "Drinking and using are not an option. Drinking and using are not an option."

She met her husband Jeff in a 12-Step program.

"We were dating, which can be dangerous in recovery," she says. "They say not too early, don't get with another addict. But the truth is no one can understand the life that we have to live to keep this life other than someone who's living it. I always say you either get drunk together or you stay clean together, so for 17 years, we've been clean together."

Every five years, Jeff and De Anne Dwight renew their vows.

Dwight started working in radio again and going to Pima Community College. She spent time working at her church, where she met Karen Wendling, the church's former children's minister. The two worked together around 10 years ago but remain friends today.

"You're friends with her because she makes you a better person," Wendling says.

Dwight comes from a family of nurses and earned her bachelor's degree in nursing from Grand Canyon University. She was licensed as a registered nurse in 2010.

"That was harder than getting clean and sober," she says. "I am not science-y, so it was hard for me, and it was accelerated."

With her eyes on a job at Banner-University Medical Center, she started at the hospital first as a housekeeper and then became a patient sitter.

On every application she has checked that box. Yes, she is a convicted felon.

"Doing the next right thing and being honest, has it caused a problem? Not a problem, I just had to do extra steps," she says.

The presidential pardon doesn't change that — she still has to check the box — but now she has a powerful stamp of approval.

The former president himself.

Paying freedom forward

Since leaving treatment, Dwight has always volunteered with people, especially women, in recovery.

"What she does is try to affect women who are trying to get off drugs and show them there is a better way and you can be free of this," Wendling says. "It's what she does in her every day life now."

Dwight started working on her pardon first in 2007, but it wasn't a priority. Dwight already believed that God has forgiven her.

"I started working on it again, and it matters because I want other people to know that if you're a felon or a drug addict or you cannot overcome something, there's hope," she says.

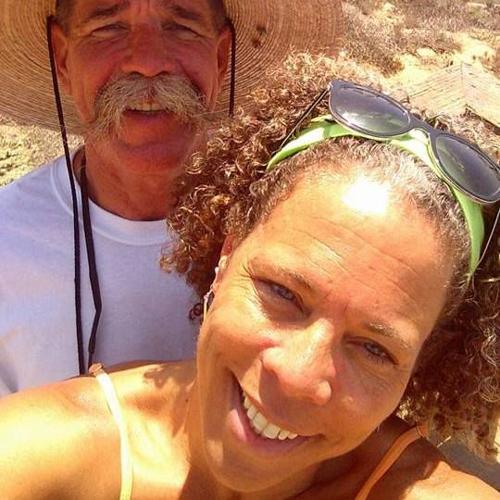

De Anne Dwight wants others to know what freedom feels like.

She invites the women she mentors into her home so they can see normal life — dirty dishes in the sink, two crazy dogs, walls that will never quite be white. No drugs, no alcohol, no addiction.

"She was bringing me over to her house, which was just amazing, because I just got released from prison, and this lady is taking me to her house," says Jennifer McPheron, who is now director of Miracle Center, a Christian nonprofit that supports homeless adults. "It helped to save my life, and she didn't think twice about it."

McPheron, 38, approached Dwight at an AA meeting after the older woman shared her story.

"When I met D, I was just talking to a lady like, 'I'm going to go back to prison. This is too hard for me,' McPheron says. "I was still on parole and knew if I used again, life would be easier in prison. They told you what to do and how to live, but when I heard D talk, I thought, 'Okay, if there is any hope that I could be like her, then maybe this is worth it and I can give it a shot."

Rachel Redman, a special education teacher in Sahuarita, is another woman who approached Dwight after hearing her story.

"When I was coming out of one of the darkest times in my life, she really helped to guide me on to a path of integrity, where I was able to face my past and deal with the consequences of it and then grow," says Redman, 35. "She and her husband Jeff opened up their home to me. They were like my adopted family here in Tucson when I literally had no one in Tucson. They had me over for dinner every week, and she was really an important person in my life being restored."

That's one of the reasons Dwight continues to attend recovery meetings regularly — to share hope. When she was in recovery, she remembers lapping up those stories of victory.

"One of the things I love about her is that she got her life back, but has given it back to other people, and that inspired me to be where I am today," McPheron says.

The mission statement for Dwight's life is freedom — for her and those around her. The word is actually an acronym, which stands for fellowship, restoration, education, encouragement, discipleship, oneness and mentoring.

"She was in some dark places for a while in her life..." Jeff Dwight, 55, says. "To keep somebody from having to go through that and help somebody out, that just fills her heart."

Pardoned

Although Dwight has no problem sharing her story, she usually limits how much patients know of her background.

But sometimes, she can't resist.

Since getting her nursing license, De Anne Dwight has worked at Banner — University Medical Center and several rehab treatment centers.

"I felt so bad for our patient one day," she says. "He was just not having a good day and was drunk ... that day he just was like, 'I'm a felon, and I can't get a job,' and I said, 'Honey, you've got the wrong nurse today.'"

After earning her license in 2010, Dwight went back to school for her master's degree, which she received in 2013.

She told this man and others like him to start small. Just do the next right thing. Recovery takes time.

"I don't know what God is going to do for me next," she says. "After this pardon, after I got released from jail, that was 17 years apart, but I'm excited... It's the little things in life to look forward to. It's just normal life things. You don't take anything for granted."

She hopes that the other 63 other men and women who received a presidential pardon on Jan. 17, 2017 take advantage of the opportunity to give someone else hope.

"I think she is almost the poster child of someone who deserves this pardon, because she is a completely different person than she was when she committed those crimes..." Redman says. "She went from being someone who was 100 percent concerned about herself and was totally entrenched in her addiction to being someone whose whole life is about serving other people and serving God and trying to use her past for good."

The formal letter Dwight received from the White House concluded with Obama's signature and these words: "I applaud your ability to prove the doubters wrong, and to change your life for the better. So good luck, and Godspeed."

This is life forgiven.

During her interview with the FBI for the pardon, Dwight's first thought when receiving her visitor's badge was not fear of getting caught or guilt for past sins.

She wanted to take a selfie.

"I'm sitting in the FBI, and I don't have any anxiety, and I'm not nervous because I have nothing to hide," Dwight says. "I had everything to hide before. It's just that doing the next right thing all the time, it just becomes life."