Vishnu Reddy, the third and last child in his family, grew up in a remote village with spotty electricity and dark night skies.

The nearest town was Chennai in India, where he was born in 1978. This was where he first began gazing up at the stars.

Almost two decades later, when Reddy was working as a copy editor in a New Delhi newsroom, he jumped at the chance to cover a lecture by Tom Gehrels, an internationally recognized planetary scientist and astronomer, one of the first members of the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory at the University of Arizona and founder of the Spacewatch Program, which surveys the sky for near-Earth asteroids.

After the lecture, Reddy and Gehrels took a cab together so Reddy could interview him. “Why should Indians care about asteroids?” Reddy asked. “There’s all kinds of problems in this world: poverty, food, shelter.”

People are also reading…

India is surrounded by water on three sides. An impact from an asteroid could cause a tsunami. People could die. Small asteroids are especially dangerous because there are many more of them, Gehrels said.

“Can amateur astronomers do anything?” Reddy asked. Gehrels told him there are many people in the U.S. with small telescopes who discover and track asteroids that are eventually named.

“I’m going to do this,” Reddy said.

“You’re a very enthusiastic young man,” he remembered Gehrels saying, “but I don’t believe you.”

“I got ticked off,” Reddy said. So he returned to the newsroom, filed his story and began researching everything he could about asteroids for the next three years.

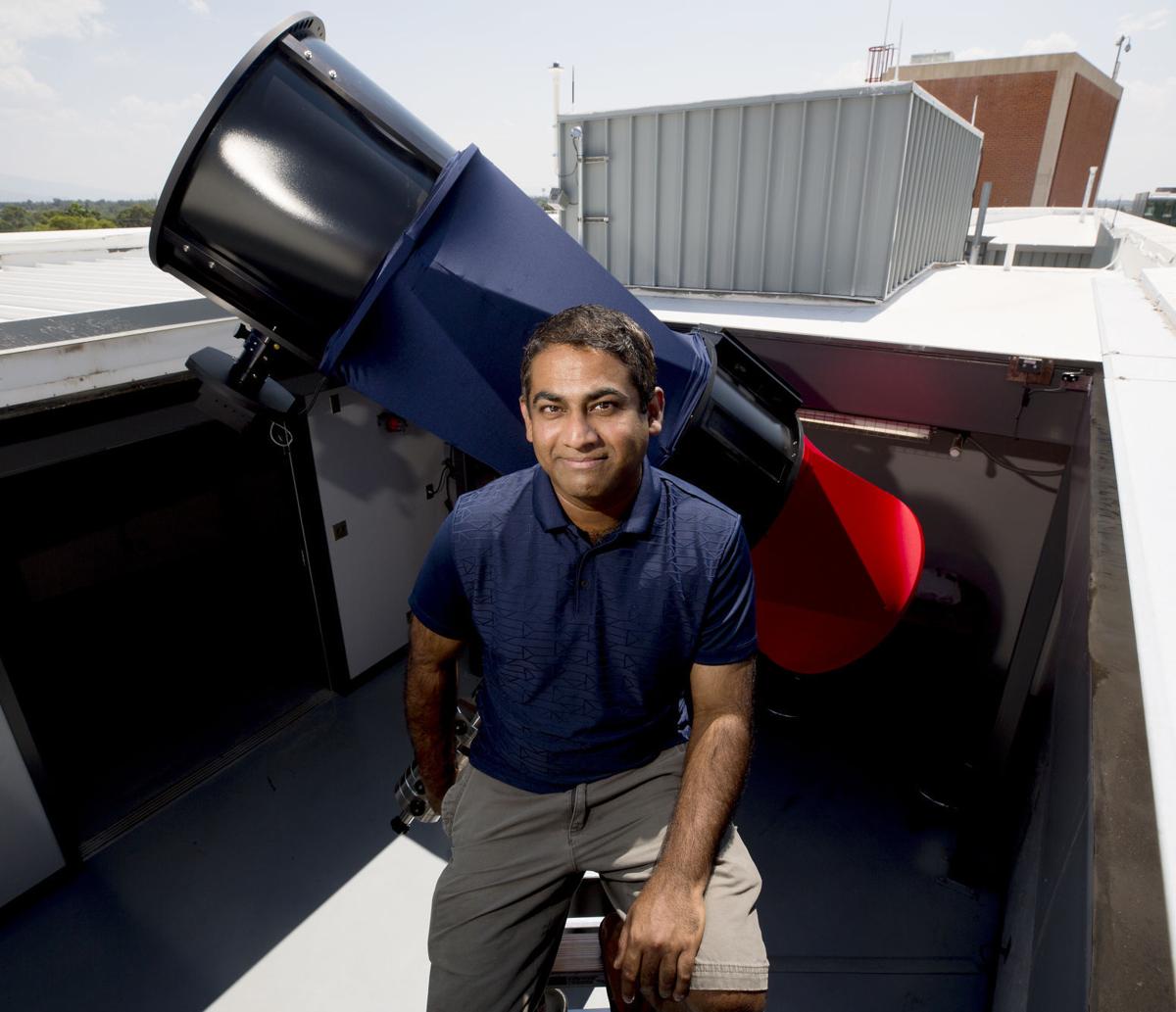

Reddy is now an assistant professor at the UA and sits two doors down from Gehrels’ old office in the Kuiper Space Sciences Building, where he characterizes near-Earth asteroids for impact hazards and mitigation.

He was recently in the news for coordinating a national-scale drill to mitigate an asteroid threat, and, this past spring finished a project with five UA seniors to build two telescopes for much less than buying them would cost.

The telescopes are now housed in the sixth floor of the Kuiper Building and are used to characterize Earth’s satellites, asteroids and space junk.

Early influences

Reddy’s parents were doctors. They lived in a small village by choice, to help the sick and poor. “We were never poor but we were never rich,” he said. “I found satisfaction in what I had.”

He remembered one morning when he was 4 years old playing in the dirt of his front yard when he saw a rocket launch. He lived near a space agency’s launchpad.

“It’s like what people would have seen in Florida in the ’60s,” he said.

He found space fascinating. “But then my path went in another direction.”

“My dad did not see that (astronomy) was viable financially to survive,” Reddy said.

Reddy started studying filmmaking. When he brought home his first telescope as a teenager, his dad said, “Why are you looking at the stars?” He’d rather him watch movies to prepare for his future.

Despite the tension, his family did what they could to support him. His sister bought him his first pair of binoculars to observe the asteroid Vesta in the night sky. He made drawings, which he still has, to track its motion through the sky.

Reddy eventually began working in Bollywood, but he was frustrated by the unsteady nature of the work.

He went back to school and got a master’s degree in journalism while also working in a newsroom in New Delhi.

He lived in a 10-by-10-foot studio apartment with a roommate who was also interested in astronomy.

It was during this time that he had his life-changing interview with Gehrels.

A spark

Reddy got serious about his dreams to be an astronomer, but he was still a journalist.

On a typical day, Reddy would wake up at 10:30 a.m. in the urban slum where he lived, then head to the newsroom. He didn’t have to be at work until 4 p.m., but he’d get in early to start researching asteroids.

At 4 p.m. he’d start work, deciding which stories to run and editing copy throughout the day. After midnight, his shift would end and he’d return to his meticulous research on the only computer in the newsroom with internet access.

During this time, Reddy accumulated six binders of research on asteroids and contacted planetary scientists and amateur astronomers around the world.

He’d catch naps when he could find them, like in elevators. “I’m an opportunistic sleeper,” he said simply. “It’s just a matter of practice.”

A telescope

He sought access to a telescope so he could start discovering his own asteroids. He contacted the big institutional observatories in India.

“They were all freaked out because they thought I was doing an investigative piece,” Reddy said.

Eventually, Greg Paris, an amateur astronomer in San Clemente, California, tipped Reddy off about a company called Meade that sold telescopes at a discounted price, but still thousands of dollars.

At the time, Reddy was making $30 a month, “Which is low even for Indian standards,” he said.

Paris offered to buy it for him with the stipulation that Reddy would pay him back when he could.

“I didn’t even know the guy,” Reddy said. Eventually, a philanthropist gave him the money.

But getting the telescope to India took three years, and the import duties drained him of the money he needed to buy the cameras for the telescope.

“In the meantime, astronomers had discovered all of the asteroids that could be discovered with this 12-inch telescope,” Reddy said. “So I was kind of depressed.”

Then he met Roy Tucker.

Tucker is an American amateur astronomer whom Reddy contacted and is now an electrical engineer at Imaging Technology Laboratory, a research group of Steward Observatory. Tucker offered to be online to discuss asteroid hunting in real-time. Reddy was the only one who took him up.

“I quickly learned that Vishnu had an even greater interest in asteroids than I did,” Tucker said. “It was obsessiveness channeled into a productive line.”

Reddy told him the trouble he was having with getting a telescope, and Tucker agreed to host him in Tucson for a couple of weeks to teach Reddy to find asteroids with amateur equipment in a place with darker skies than New Delhi.

“You need money to go to the U.S.,” Reddy said. “So I sold everything I had in my tiny apartment and landed in front of the U.S. Embassy.”

Going to America

There were two lines at the embassy for passports. “One guy was rejecting everyone’s application, so I jumped into the other line.”

He asked why he was going to the U.S., and Reddy said honestly, “I’m going to discover an asteroid.”

He was granted a passport and landed in Michigan, where he stayed with a host. Then, he took a bus from Michigan to Tucson. “It took like six days,” Reddy said. “I was 24 years old; I saw the real U.S. and met some really crazy people on the bus.”

In Tucson, Tucker helped him put his binders of knowledge on asteroids to work.

Astronomers find asteroids by taking photos of the sky multiple times. The stars in the sky should be fixed in place. Astronomers will quickly flip between images, and if they see a point of light moving with respect to the fixed stars, they know it’s an asteroid.

One evening while he was napping on Tucker’s couch, he was shaken awake.

“You found an asteroid!” Reddy said Tucker told him. He and Tucker have been friends ever since. To this day, they meet Friday nights for pizza and bad sci-fi movies.

Reddy submitted two potential asteroids to the Minor Planet Center, a hub for observational data on asteroids and comets, and one was a new discovery.

He looked at an email they had sent, full of numbers and symbols that he didn’t know how to decipher. Tucker pointed at a number in parentheses and said, that’s your asteroid. “I was expecting a certificate or something,” Reddy said. He named the asteroid 78118 Bharat, which is India in Hindi.

During the rest of his asteroid tour of the U.S., he reconnected with Gehrels and met with idols he discovered through his middle-of-the-night research in India.

Back to school

When he returned to India, Reddy started studying for the GRE and applied to the University of North Dakota. They offered a program to transition nonscience majors into science doctoral students. He started in 2004 and earned his doctorate in space studies five years later.

He was a top student, said Paul Hardersen, Reddy’s master’s thesis advisor at North Dakota and now a senior scientist at the Planetary Science Institute in Tucson. “He’s very self-motivated and knows what he wants to do and actually does it.”

“He’s realistic and compassionate and well-rounded,” he continued. “He doesn’t think he’s the best thing since sliced bread, he just works hard, which is different for science.”

Reddy worked on space missions out of Europe for a few years, where he met his wife, Lucille, also an astronomer.

He eventually made it back to Tucson where he worked at the Planetary Science Institute.

He was hired as an assistant professor in the UA’s Lunar and Planetary Laboratory in 2016 and taught his first undergraduate class last spring semester.

Reflecting on where he is now, Reddy said, “I am getting paid everyday to do my hobby. That’s what you want to feel.”

Toward the future

Reddy, 39, still has his career ahead of him. And although he’s changed his career path many times, the one thing that has held it all together was his determination.

So when he took on the telescope-building project last academic year, it was no different.

“He’s invested in doing it right and making sure it gets done,” said Sameep Arora, one of the seniors on the project, now an intern at American Airlines.

The seniors, under the guidance of Reddy, built two 24-inch telescopes to track satellites and space junk in Earth orbit for a fraction of the price it would have cost to buy them. The students gained valuable experience while fulfilling graduation requirements.

Setbacks in the project, such as parts not coming in on time, were dealt with by Reddy.

“There was some frustration, but he would use it as a drive to move the problem forward,” Arora said.

Reddy also made time to relax with his students, tell jokes, stories, and “give personal insights on life,” Arora said.

He does the same thing in his general education classes, which he loves to teach, a trait he thinks he inherited from his parents, who found satisfaction in helping people.

His own piece of advice: “I told my students that it’s OK to not know what you want to do now. But once you do, go out and do it.”

Contact Mikayla Mace at mmace@tucson.com or (520) 573-4158. On Twitter: @mikaylagram