Sept. 24 was landing day for the University of Arizona-led OSIRIS-REx asteroid sampling mission.

For Dani DellaGiustina, it was also launch day.

The moment the spacecraft released its capsule filled with rocks and dust from asteroid Bennu, the 36-year-old U of A assistant professor assumed command of the robotic probe roughly the size of a passenger van.

Over the next six years, DellaGiustina and her team will guide it to its next target: a potentially dangerous near-Earth asteroid called Apophis.

That mission, known as OSIRIS Apophis Explorer or OSIRIS-APEX for short, officially got underway when the Tucson-born spacecraft fired its thrusters and angled away from Earth about 20 minutes after jettisoning its sample-return capsule.

“It's still pretty dizzying to be honest. Sometimes I'm just like, 'Wait, what do I do for a living?' " said DellaGiustina, a 2008 U of A graduate who also earned her Ph.D. in geosciences from the university in 2021. “I'll get frustrated with paperwork or something, and I have to just take a step back and be like, 'Wow, what I get to do is freaking amazing.' It’s such a privilege, and I kind of can't believe it happened sometimes.”

NASA approved the university's proposed mission to Apophis last year, adding another $200 million in funding to a project that has already cost almost $1.2 billion.

If everything goes according to plan, OSIRIS-APEX will catch up to its new target in June of 2029, about two months after the potato-shaped asteroid roughly the length of the Empire State Building streaks past Earth close enough to be visible in the night sky over parts of Europe and Northern Africa. That is slated to occur on April 13, 2029, which is a Friday — a Friday the 13th to be exact.

“An object that big does not get this close to the Earth very often, maybe once every 7,500 years,” DellaGiustina said. “So something this big hasn't gotten this close to the Earth in recorded history.”

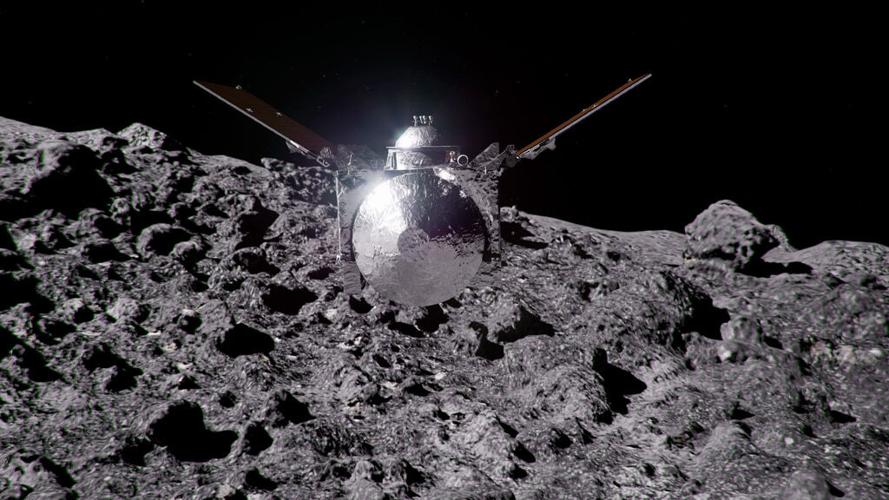

A NASA animation shows the spacecraft now known as OSIRIS-APEX as it prepares to use its thrusters to stir the surface of asteroid Apophis in a maneuver scheduled for September of 2030.

The idea of sending OSIRIS-REx on an extended mission first came up about three years ago, before the spacecraft had even touched down on Bennu, but everyone was too busy to really think about it then, she said. The mission team started to take a serious look at where to go next only after the asteroid samples were safely stowed and on their way back to Earth.

At about that same time, DellaGiustina was named as deputy principal investigator for OSIRIS-REx. She said planning the spacecraft’s next adventure “kind of became my job.”

“We were really looking for what we called rendezvous targets, objects we could eventually get in orbit around,” she said. “After this huge exhaustive search, the best and most compelling target was Apophis.”

Big questions

DellaGiustina grew up as an “Army brat.” Her childhood was spent bouncing among military towns across the Mountain West, most of them along the U.S.-Mexico border, including the Hereford area near Sierra Vista.

(If you’re wondering, she said her last name is pronounced “De-la-Jew-Stina.”)

Her longest stretch in one place as a kid was the five years she spent in El Paso, Texas. That’s where she enrolled at a local community college and signed up for an astronomy class that changed everything for her.

Though she did not have a strong background in math or science, she said she was drawn in by the big questions scientists seemed to be asking: “Things that I thought you traditionally answered with philosophy like, What is our destiny and how did life originate?”

A year later, DellaGiustina transferred to the U of A with stars in her eyes, then detoured into planetary science after taking an introductory class taught by Dante Lauretta, the future Regents’ Professor who would one day lead NASA’s first asteroid-sampling mission.

“That is how I got connected to Dante and OSIRIS REx: just taking some general classes like meteorites 101 to explore the different topics in the field,” she said.

Thoroughly inspired, DellaGiustina landed a prestigious student fellowship from NASA’s Institute of Advanced Concepts at age 19 with a proposal to have astronauts hitch a ride to Mars on an asteroid and use it as a shield to protect them from solar and cosmic radiation during the long flight. The 2006 prize came with $9,000 and earned her a write-up in the Tucson Citizen.

The next thing she knew, she was being asked by Lauretta to design an actual experiment to test the radiation shielding properties of a real asteroid.

“I kind of knew then she was pretty special," Lauretta said. "She’s smart and motivated and has got that kind of leadership air around her. Once she knows what needs to get done, she does it or helps the team get it done.”

NASA ended up rejecting that first version of the university's proposed OSIRIS mission, so DellaGiustina’s student experiment never got to fly in space. But the experience gave her “a wild and really interesting crash course in how to build a spaceflight instrument,” she said.

“I was a junior in college when I was really putting it together. I got to recruit other students to help me. I presented the results to NASA’s site selection panel, and it got really high reviews, which was awesome. It gave me a lot of confidence at a very young age that, OK, I can kind of see how this is done, and I guess I can do it.”

DellaGiustina graduated from the U of A in 2008 with a degree in physics and a minor in planetary science, and then she headed off to graduate school. Specifically, she traveled 3,600 miles north to the University of Alaska-Fairbanks to study ice, something she thought would help her better understand the icy moons and water-bearing asteroids that so fascinated her.

During field work in the summer of 2018, University of Arizona scientist Dani DellaGiustina uses a hammer to generate an "active seismic signal" to test instruments in Greenland for a future NASA lander mission to Jupiter's moon Europa.

As you might guess, Fairbanks turned out to be “a great place to do that,” she said. Before long, she was doing field work on glaciers in Alaska and ice sheets in Greenland.

She still finds time for that kind of research. Last summer, she spent six weeks camped on an ice sheet in Greenland, two hours by helicopter from anywhere, testing seismometers and other instruments she hopes to one day send to explore the frozen moons of Jupiter or Saturn.

“I've been lucky that I have managed to continue to maintain a career that involves doing field work in pretty extreme environments and also doing spaceflight projects, which is just so much fun,” she said.

After grad school, DellaGiustina returned to the U of A Physics Department in 2012 to work as a research scientist in the photovoltaic lab. She said she was looking for something with more of “an environmental focus,” after witnessing the impacts of human-caused climate change firsthand in some of the world’s coldest places.

“There's glaciers that I've been going to for field work on and off for about a decade, and just seeing the change in 10 years, it's startling,” she said.

But the lure of space was just too great. After about a year and a half in the physics lab, she landed a job as a junior image-processing scientist on OSIRIS-REx.

She would go on to lead the imaging team for the mission, a job that took on much greater significance when the spacecraft reached Bennu and discovered a far rockier surface that did not respond to thermal instruments the way researchers expected it to.

The only way to pick out a safe place for OSIRIS-REx to touch down and collect samples was to photograph the asteroid in as much detail as possible, using three onboard cameras, all built at the U of A. The intensive imaging campaign began in late 2018 and continued almost nonstop for about a year and a half.

“I’ve probably never worked more in my entire life," said DellaGiustina, adding with a laugh, “It was a really amazing opportunity that I would never want to have again.”

Her team included four full-time image analysts and another 10 undergraduate students, brought in to help them chart potentially spacecraft-killing boulders on the asteroid. The result was the highest resolution map ever produced of a planetary surface, Earth included. DellaGiustina and her team imaged every rock, dirt pile and crater on Bennu down to about 2 square inches in size.

You already know what happened next. OSIRIS-REx safely collected its sample from the asteroid on Oct. 20, 2020, and returned to Earth last week to deliver its cupful of scientific treasure to the mission team in the Utah desert west of Salt Lake City.

Long journeys

DellaGiustina watched REx end and APEX begin from the flight operations center for both missions at Lockheed Martin Space, the aerospace company outside of Denver that built the spacecraft.

Then she got on a plane to Houston so she could see the sample from Bennu as it was opened for the first time at NASA’s Johnson Space Center. Just because she has a new asteroid mission to lead doesn’t mean she is finished with the old one. Lauretta said she will stay on with REx as his deputy through the sample analysis work.

“You wouldn't be able to keep me away,” DellaGiustina said. “It's too important, and I am too invested. I've spent my entire adult life on this project, basically.”

University of Arizona assistant professor Dani DellaGiustina, pictured here at a press conference in 2020, is now serving as the principal investigator in charge of NASA's extended asteroid science mission called OSIRIS-APEX.

Lauretta said DellaGiustina has worked on OSIRIS-REx almost as long as he has, and the two of them have become like siblings over the years — occasionally competitive with each other, but always pulling for the same team.

He said he has tried his best to prepare her to lead her first space mission. Principal investigator is the job of a lifetime, Lauretta said, but it requires bureaucratic skills as well as scientific ones. You have to learn everything from working with NASA Headquarters to tracking the federal appropriations process.

“It's not something to sign up for lightly, because Apophis is a six year commitment,” he said. “Most people don't understand signing up for something of that length. It's hard, and you're tired at the end of it.”

Planetary scientists already had a great deal of interest in Apophis before the OSIRIS team chose it. DellaGiustina said both the European Space Agency and Japan's Aerospace Exploration Agency are still considering sending space probes there.

“This is a really infamous asteroid in our community,” she said.

The space rock appeared to be on a collision course with Earth when it was first discovered in 2004 by scientists at Kitt Peak National Observatory. Subsequent observations ruled out an impact for the next century at least, despite the near-miss in 2029 and two more close approaches in 2036 and 2068.

Now researchers are eager to see how the asteroid might be altered by its upcoming brush with our planet’s gravity. Will it start to spin differently? Will there be landslides or other surface disturbances?

“There are a lot of predictions,” DellaGiustina said. “This is just an incredible natural experiment that we're being given.”

Apophis is also a different kind of asteroid than Bennu is — a stony collection of silicates and metals instead of a carbon-rich rubble pile — so studying it close up should help expand our knowledge of how such objects behave and how we might defend our planet from one someday.

First, though, OSIRIS-APEX has a lot of space to cover.

To catch up with its target, the spacecraft needs to make several sweeps through the inner solar system, some of which will carry it closer to the sun than it was designed to get. During those searing flybys, DellaGiustina and company plan to position OSIRIS-APEX's solar panels to block the heat from some of its more sensitive components, a maneuver they're calling "the fig leaf."

They hope to be in stable orbit around Apophis by August of 2029.

Though the spacecraft is not set up to collect any more samples — it only had the one return capsule, after all — the onboard instruments should be able to collect detailed images of the asteroid, data about its composition and maybe some telltale signs of water.

In September of 2030, the team plans to steer the probe in close and use its thrusters to stir the surface of Apophis, revealing whatever material lies beneath. Later, DellaGiustina said, they might also try powering up the sampling arm one last time so they can “poke the asteroid" and observe the results.

The trip to a second asteroid was made possible by the spacecraft’s near-perfect performance during its voyage to Bennu and back.

“We get to take advantage of that good stewardship to have another mission," she said. "The thing we have expended the most of is spacecraft fuel, but there is still enough fuel to support an entire mission to Apophis. We could probably even do another extended mission after that.”

It’s not unusual for NASA to try to squeeze additional science out of still-functioning spacecraft, but it usually involves allocating more money to let an orbiter keep orbiting or a rover keep roving. In this case, the U of A's Lunar and Planetary Laboratory proposed an entirely new mission.

“It was a really satisfying experience, because we got such high marks” from the NASA review committee, DellaGiustina said. “I think they said this is the most imaginative extended mission they had seen in recent history.”

And as the journey unfolds, OSIRIS-APEX is expected to provide current and future U of A students with unparalleled learning opportunities like the one that helped propel its principal investigator to where she is today.

DellaGiustina, who turns 37 in a week, said there is a plan already in place to “completely turn over” the mission team, with current leaders training their replacements to take over for them by the time the spacecraft reaches Apophis.

"We place such a high value on opportunity. We take that very seriously," she said. "I mean, part of that is my own background, right? I am 100% a product of the fact that I got to start this work as an undergrad, which is just nuts."

Samples from the asteroid Bennu dropped into Utah’s western desert Sunday morning, as the University of Arizona-led OSIRIS-REx space mission came to an end. Video courtesy of FOX13.