The University of Arizona’s efforts to prevent the respiratory infection valley fever in dogs just got a major boost from the federal government.

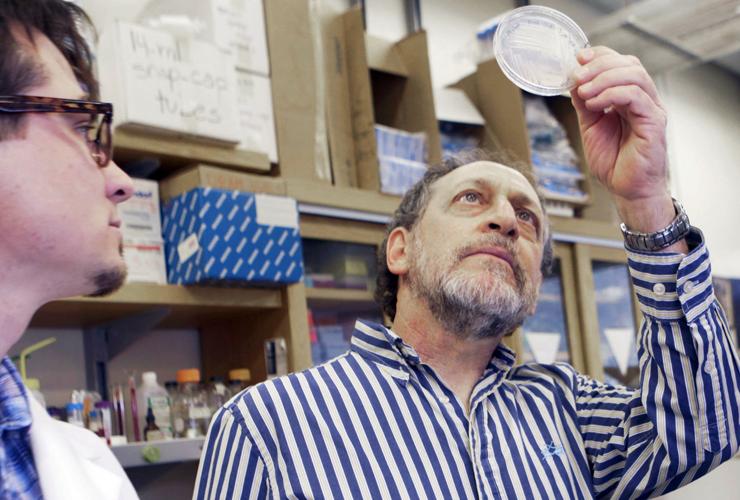

A $4.8 million, four-year grant from the National Institutes of Health announced this month provides needed funding to get the delta-CPS1 vaccine to market, said Dr. John Galgiani, director of the UA Valley Fever Center for Excellence and principal investigator of the NIH grant.

The vaccine could hit the market as soon as five years from now, Galgiani said.

Though the vaccine will be initially developed for dogs, the intent is to eventually use it in humans, too, UA researchers say. There is currently no prevention or cure for valley fever, which is potentially deadly in both humans and dogs.

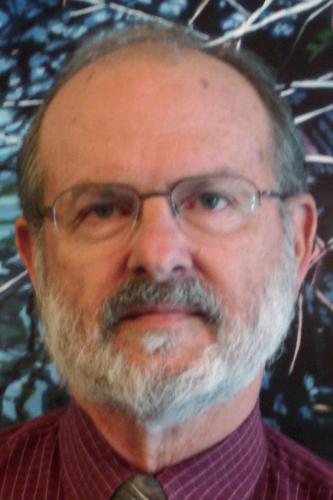

The live vaccine was invented by UA fungal geneticist Marc Orbach. It is a mutant spore that has already protected mice from valley fever, but it has never been tested on dogs. The UA holds the intellectual property rights on the vaccine.

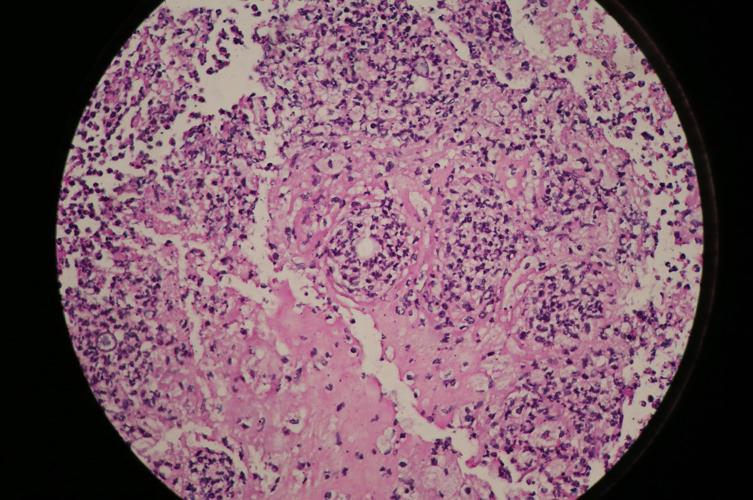

An estimated 30,000 people and 60,000 dogs in Arizona get sick from valley fever, also known as coccidioidomycosis, every year. The cocci fungus that causes the disease is found mainly in dusty areas of Arizona and California. State health officials say it contributed to the deaths of 54 people in Arizona last year.

“It’s a strategic decision to go to dogs first,” Galgiani said. “We will see if it’s harmful for dogs, see if it works. ... It will make the momentum to go to humans that much stronger.”

A canine vaccine would go through the U.S. Department of Agriculture Center for Veterinary Biologics to get to market, while a human vaccine would need to go through the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for approval. The FDA is generally a slower path, UA officials say.

The NIH funding comes from its National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. The UA research team also applied for $250,000 in seed money for its vaccine development from the Arizona Biomedical Research Commission but was turned down, Galgiani confirmed.

The NIH grant is an encouraging validation of the vaccine and the UA’s plans for developing it, he said.

Anivive Lifesciences Inc., a California-based biotechnology company, has licensed the vaccine from the UA through Tech Launch Arizona and will provide additional investment and expertise to fully develop the dog vaccine, Galgiani said. Tech Launch is the UA’s commercialization arm.

Scientists at Colorado State University are also collaborating on the UA’s vaccine project through CSU’s College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences and the lab of Dr. Richard A. Bowen.

Some dogs with valley fever are euthanized because their owners cannot afford to treat them. The anti-fungal medication that is often necessary to keep valley fever at bay for the rest of a pet’s life costs $4 to $6 per day, and blood tests and associated veterinary costs can run into the thousands. Also, blood tests can give false negatives and require additional testing and money.

Dogs will often lose large amounts of weight and the disease causes lameness and pain, or paralysis if the infection moves into the bones of the back.

“This should drive us a long way. I am ecstatic and this is exactly the kind of funding we needed to get this ready for clinical trials in dogs,” said Dr. Lisa Shubitz, a UA veterinarian and researcher who is part of the delta-CPS1 team.

Shubitz has seen firsthand the effects of canine valley fever on many of her patients and on her own dogs, too.

The risk factor for acquiring valley fever is the same for dogs as for humans — breathing — and in parts of California and Arizona, impossible to avoid.

It takes inhaling just one cocci spore to become infected, though, like humans, most dogs who acquire valley fever will not get sick from it. For the ones that do, the disease can result in amputations and worse.

At least two previous serious attempts at creating a valley fever vaccine failed. The first resulted in sore arms but no conclusive proof it worked. The second was a laboratory-created hybrid protein vaccine made in a yeast strain using DNA from the valley fever fungus. It looked promising but stalled because of its cost.

Politics and funding are problems for getting any valley fever vaccine to market because it is a regional, not national, disease. In humans, it affects fewer than 200,000 people per year, which gives it “orphan” status. That also means it’s harder to get drug companies interested.

But since delta-CPS1 is a spore, there’s no expensive protein purification step as there was with other vaccine attempts.

The UA team faces several more hurdles in getting its vaccine to market, including proving to the USDA that it is safe and that it works. The team also needs to figure out how to make the vaccine as a commercial product with a shelf life.