After a high-stakes career as a pediatric cardiologist, Richard Donnerstein has chosen to spend the time he has left staring off into space.

In 2008, the newly retired Tucson medical doctor enrolled in an introductory astronomy class at the University of Arizona. He would eventually work his way through the entire course catalog for an undergraduate degree in the field, then convince one of his professors to take him on as a researcher.

“After I retired, I obviously had to find something to do, and I’m way too uncoordinated to play golf,” Donnerstein said. “So I decided to take some courses, and I just loved it.”

Sixteen years and about two dozen scientific publication credits later, the 82-year-old’s post-retirement hobby has earned him a prestigious national award for amateur astronomy.

On Jan. 16, the American Astronomical Society named Donnerstein as this year’s recipient of the Chambliss Amateur Achievement Award for his “significant contributions” to the detection of some of the faintest and most confounding galaxies in the universe.

Richard Donnerstein, a retired pediatric cardiologist, has won a national award for amateur astronomy after helping University of Arizona scientists develop a way to detect some of the faintest and most confounding galaxies in the universe.

Donnerstein was recognized for his work on a U of A-led project called Systematically Measuring Ultra-Diffuse Galaxies, or SMUDGes for short.

“That’s exactly what they look like. They look like a smudge, you know, like somebody left a fingerprint on a photograph,” he said.

Donnerstein developed a computer algorithm capable of identifying these faint objects in images collected during massive surveys of the entire night sky above both the Northern and Southern hemispheres.

“These particular galaxies are interesting because they can be quite big. They can be the size of the Milky Way, but only have maybe 1 percent of the amount of stars, so they’re really quite faint,” he said. “We basically started looking for them and found over 7,000 of these things spread everywhere.”

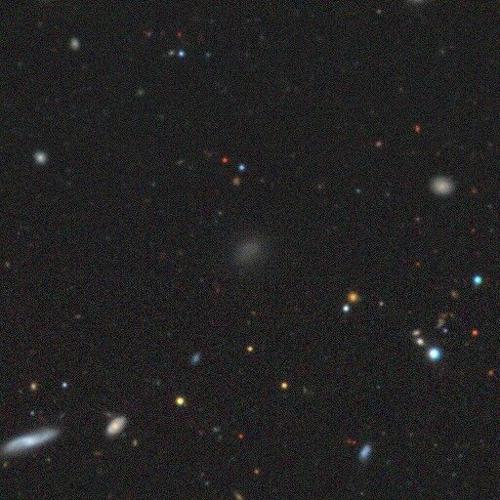

The smudge at the center of the frame is what is known as an ultra-diffuse galaxy, which are faint and difficult to resolve because they contain far fewer stars than other galaxies of their size. Tucson amateur astronomer Richard Donnerstein has won a national award for his work to help detect such galaxies so they can be studied.

Their existence raises a host of questions astronomers are still trying to answer, Donnerstein said. “Why are they here? How do they form? What holds them together? By having enough of them (to study), we can do some statistical analysis and get a rough idea of why they’re there and why they haven’t fallen apart.”

Westward bound

Donnerstein was born in New York and raised in South Florida. He went to New York University for medical school and Yale University for his residency and fellowship, before joining the Army and serving four years as a pediatric cardiologist at Walter Reed hospital in Bethesda, Maryland.

The self-described “die-hard Easterner” joked that he barely knew where Arizona was in 1985, when he landed a job at what was then called University Medical Center in Tucson.

“They had a superb pediatric cardiology program. At that time, it was probably one of the world’s leading places for research on echocardiography,” he said. “The job perfectly fit what I was looking for.”

He’s been here ever since.

Donnerstein said there is “very little” similarity between the work he did as a heart doctor and what he does now as an amateur astronomer.

“That is why I’m doing it, I think. I enjoyed my career, and I certainly miss many, many of my patients, but when I retired I looked to do something as far away from medicine as possible,” he said.

As it turns out, trying to unlock the mysteries of the cosmos is a lot less stressful.

“You don’t have to worry about bad decisions. If you’re off by a factor of 10, nobody cares,” Donnerstein said with a laugh.

The computer programming stuff came naturally to him, he said, because he studied engineering before he went to medical school and has been working with computers since the days of punch cards.

“As a matter of fact, I was doing it even prior to punch cards, when we were just pushing buttons on machines,” Donnerstein said.

His research focus in medical school was on using computers to analyze heart sounds.

To help sift out the SMUDGes in a universe filled with billions of other galaxies, Donnerstein said he borrowed a machine-learning program first built for “telling cats from dogs from monkeys from elephants, that sort of thing.”

“It was an algorithm designed to actually discriminate between various types of images,” he explained. “I adapted that for galaxies, and it worked quite well.”

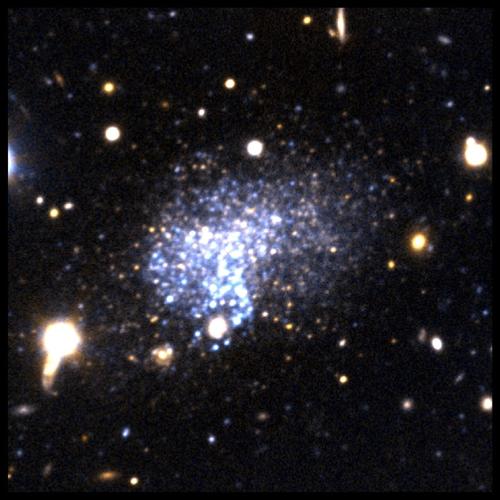

A composite image taken by the Magellan Clay Telescope in Chile shows Corvus A, one of the dwarf galaxies being studied by researchers at the University of Arizona with the help of retired medical doctor turned amateur astronomer Richard Donnerstein.

‘Secret sauce’

The quest to catalog and study ultra-diffuse galaxies is being led by another award-winning local astronomer. Dennis Zaritsky is deputy director of the U of A’s Steward Observatory and principal investigator for the SMUDGes Project. He has also served as Donnerstein’s research advisor for the past decade or so.

Last year, the American Astronomical Society awarded Zaritsky the coveted Beatrice M. Tinsley Prize for what it described as his “innovative observations probing the structure and evolution of galaxies.”

Zaritsky in turn nominated Donnerstein for this year’s Chambliss prize.

One glowing letter of support for that nomination came from U of A professor and astronomer David Sand, who recently began working with Donnerstein on a similar computer-driven search to help identify some of the faintest dwarf galaxies in the nearby universe.

Sand said the “secret sauce … blended by Richard” has already paid off, producing dozens of strong candidate galaxies for further study.

“Richard’s enthusiasm is contagious, and his scientific impact formidable. I have never experienced an amateur with his skill set, passion and work ethic before,” Sand wrote in his letter to the astronomical society. “He is showing once again his mastery of algorithms at scale applied to a project that will shed light on the nature of dark matter and the floor of galaxy assembly.”

The award came as a complete surprise to Donnerstein, who said the prize comes with a silver medal and an invitation to an upcoming meeting of the astronomical society this summer in Alaska or next January in Phoenix.

“I’m very flattered, very honored at my age to be able to (receive) that,” he said. “The kids and grandkids are impressed, if nothing else.”

Ultimately, though, Donnerstein is just glad to have found something to do in retirement that challenges him and makes him feel useful.

“It’s a win all the way around, actually. They obviously get free help, and, from my standpoint, I’ve learned so much and it’s kept me very busy and occupied,” he said.

And unlike an expensive hobby like golf or restoring old cars, all astronomy costs him is time.

“Working for nothing is still less expensive than what it could have been,” Donnerstein said.