The coronavirus may have killed off two Tucson museums, at least for now.

Citing its own serious financial troubles, the Arizona Historical Society board voted Friday to end its operating agreements for the Fort Lowell Historical Museum and the Downtown History Museum.

The two facilities have been closed since April 1 due to the pandemic. If they hope to reopen, they will need someone else to run them.

“This is not an easy vote,” said board president Linda Whitaker after the near-unanimous decision, “but we have to look at the data and react accordingly.”

The board also voted to end the society’s 10-year-old agreement with Arizona State Parks and Trails to operate the Riordan Mansion State Historic Park in Flagstaff. Nearly all of the public comment at Friday’s meeting concerned the early-20th-century mansion.

The decision came after society board treasurer James Snitzer delivered what he described as a “doom and gloom” financial update on the organization.

Without improved revenue and major operational changes, he said, the society’s overall budget could shrink to “a shutdown level” within two years, forcing it to close the eight museums and historic sites it owns around the state.

Friday’s action was “small potatoes” compared to what lies ahead, Snitzer said. “We’ve got some bigger fish to fry as a board later on.”

Arizona’s oldest historical agency has operated the Downtown History Museum for the past 20 years under an agreement with Wells Fargo, which owns the bank building where the exhibits on Tucson’s past are housed at 140 N. Stone Ave.

About 30 volunteers took part in the pickup organized by Caterpillar Inc. in partnership with Tucson Clean and Beautiful and the Sonoran Institute. In addition, several employees worked with the Sonoran Institute on riverbed litter quantification studies. These simple surveys identify and categorize trash found with in 10 meter by 10 meter square areas with the goal of learning ways to control pollution at its source and coming up with strategies to better capture trash once it has reached the riverbed. Here, Luke Cole with the Sonoran Institute explains more about the surveys. (Josh Galemore/Arizona Daily Star)

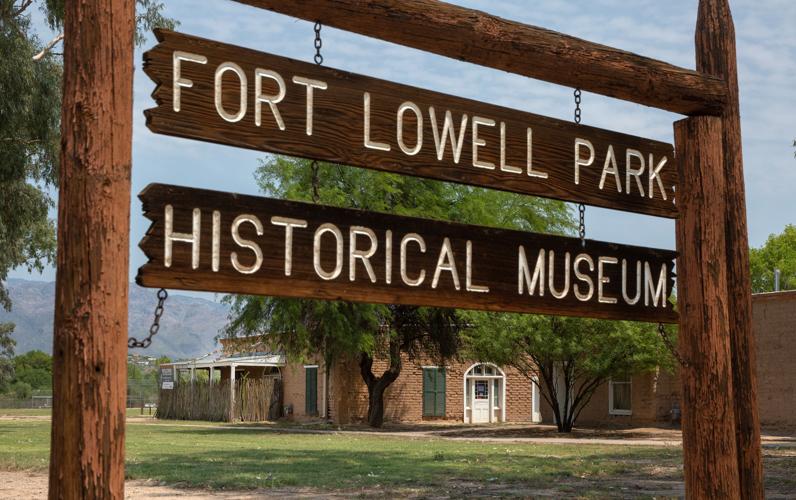

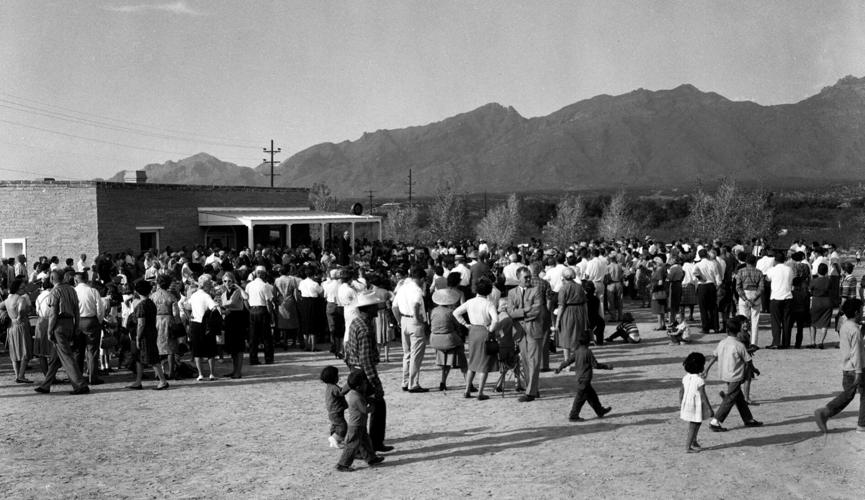

The Fort Lowell Museum was developed by Pima County in 1963 to mark the site of the military post that operated there in the late 19th century. The city acquired the museum in 1984, and the Historical Society has operated the facility since 1987.

Under the agreements, the society provides direct financial support, marketing and administrative services to the two Tucson museums, neither of which charge admission.

Most of the artifacts inside the two museums are owned by the Historical Society. Once the operating agreements end, the society will have to take custody of those items, though they could be made available for loan or exhibit in the future if new operators are found.

Assistant City Manager Albert Elias said Tucson officials are exploring some options and talking to potential partners in hopes of keeping the Fort Lowell Museum open. “We do think that’s important and worth doing,” he said.

City Councilman Paul Cunningham envisions reopening the museum as part of a larger restoration project that would include other parts of the old fort and nearby historic properties.

It could be a year before anything happens, he said, “but we’re not going to allow the property to go dormant for very long.”

Frank Flasch, vice president of the Old Fort Lowell Neighborhood Association, hopes something can be worked out.

“We’re very disappointed that the Historical Society is pulling out. The museum has meant a lot to the neighborhood,” Flasch said. “We’re looking for different ways we can keep it going.”

The future of the Downtown History Museum is far less certain.

James Burns, executive director of the Historical Society, said he got word just before Friday’s meeting that Wells Fargo intends to vacate the entire bank building where the small collection is housed.

Historical Society board members were originally set to vote on canceling their operating agreements in Tucson and Flagstaff in August, but the decision was delayed after local groups complained about being blindsided by the move.

Board president Whitaker said no one should have been caught off guard. Though the pandemic has made things worse for everyone, the society has been talking about ending these agreements for several years now.

“I don’t think we were taken seriously,” she said. “We can’t afford not to act. As a board, we are compelled to do something about this.”

Photos: Stock car racer Kelly Jones returns to the track after a six year hiatus

Kelly Jones

Updated

Kelly Jones heads for the track to run a heat in the Thunder Trucks division at Tucson Speedway, Tucson, Ariz., October 17, 2020. It was Jones first time behind the wheel at the track after taking six years off to support her two kids and husband Dustin with their racing and help run the family business.

Kelly Jones

Updated

Racer Kelly Jones, left, talks with her dad, Colin Germain, about her upcoming qualification laps in the Thunder Trucks division as husband Dustin dives into the truck cab for some last minute adjustments, Tucson, Ariz., October 17, 2020.

Kelly Jones

Updated

Kelly Jones laces up her shoes, the same ones she last used 16 years ago at age 18, prior to her practice laps at Tucson Speedway, and her return to racing after taking off the last six years, Tucson, Ariz., October 16, 2020.

Kelly Jones

Updated

Kelly Jones and her husband Dustin sit on the ramp to the trailer to talk about her qualifying run, where she placed fifth in Thunder Trucks, at Tucson Speedway, Tucson, Ariz., October 17, 2020.

Kelly Jones

Updated

Dustin Jones gives his son Devin a hug in the pits at Tucson Speedway while crewing his wife Kelly's return to the track after six years, Tucson, Ariz., October 17, 2020.

Kelly Jones

Updated

Devin Jones talks to his mom Kelly Jones while she waits in line to make her qualifying run in the Thunder Trucks at Tucson Speedway, Tucson, Ariz., October 17, 2020.

Kelly Jones

Updated

Dustin Jones gives his wife Kelly a big thumbs up as she rolls into post race inspection after her fourth place finish in Thunder Trucks, the feature race at Tucson Speedway, and her fist race in six years, Tucson, Ariz., October 17, 2020.

Kelly Jones

Updated

Thunder Trucks driver Kelly Jones gets a hug from her daughter Keirstin as the two wait in the pits for Kelly's race at Tucson Speedway, Tucson, Ariz., October 17, 2020.

Kelly Jones

Updated

Kelly Jones gets a congratulatory kiss from husband Dustin after she drove to fourth place finish in Thunder Trucks at Tucson Speedway, Tucson, Ariz., October 17, 2020. The two met as teenagers racing at the speedway.

Kelly Jones

Updated

Dustin Jones checks in with his wife Kelly before she takes to the track at Tucson Speedway for a practice run, Tucson, Ariz., October 16, 2020.

Kelly Jones

Updated

Devin Jones climbs on the family golf cart to watch his mother Kelly turn in some practice time on the track at Tucson Speedway, Tucson, Ariz., October 16, 2020.

Kelly Jones

Updated

Colin Germain takes lap times as his daughter Kelly Jones returns to the track after six years during her practice laps at Tucson Speedway, Tucson, Ariz., October 16, 2020.

Kelly Jones

Updated

Keirstin Jones unloads the new tires for the truck her mother Kelly Jones is readying to race at Tucson Speedway, Tucson, Ariz., October 16, 2020.

Kelly Jones

Updated

Racer Kelly Jones takes her Thunder Truck through turn two during a practice session at Tucson Speedway and her return to racing after six years, Tucson, Ariz., October 16, 2020.

Kelly Jones

Updated

Racer Kelly Jones talks with her family and friends about the handling of her truck after driving to a fourth place finish at Tucson Speedway, her first race after a six year hiatus from racing, Tucson, Ariz., October 17, 2020.

Kelly Jones

Updated

Racer Kelly Jones brings her truck, center in yellow, blue and black, into turn one in the night's preliminary heat at Tucson Speedway as she returns to the track after six years, Tucson, Ariz., October 17, 2020.

Kelly Jones

Updated

Keirstin Jones holds the brake pedal down so her dad Dustin can get the lug nuts off a rear wheel as he readies the truck for his wife Kelly Jones to run during practice at Tucson Speedway, Tucson, Ariz., October 16, 2020.

Kelly Jones

Updated

Kelly Jones adds sunglasses to her equipment before taking a late afternoon qualifying run in Thunder Trucks at Tucson Speedway, Tucson, Ariz., October 17, 2020.

Kelly Jones

Updated

16-year-old Kelly Germain proudly displays the back of her racing helmet in 2002. She says many other students at Saguaro High School think it's pretty cool that she races and many of the boys claim they could beat her in a race..

Kelly Jones

Updated

Nineteen year-old racer Kelly Germain (now Kelly Jones) sits on her car to weight it while her dad, Colin Germain, make a suspension adjustment to the rear of the car at Tucson Raceway Park on March 19, 2005.

Kelly Jones

Updated

Kelly Germain, back to the camera, gets a hug from boyfriend Dustin Jones, at a practice at Tucson Raceway Park on March 19, 2005.

Kelly Jones, racing family

Updated

Dustin Jones, left, and his girlfriend (now wife) Kelly Germain, with their cars at Tucson Raceway Park in 2004. They were two of the best racers in the Late Model series at TRP, and they're also a couple - an odd arrangement in the competitive world of motor sports.

These 3 race car-driving girls just made Tucson Speedway history

UpdatedThe first time she raced on the track, Quinn Davis was 5 years old.

She’ll never forget what happened.

Quinn climbed into a club car and drove 10 laps around the Tucson Quarter Midget Association’s Marana track. Then she couldn’t stop.

Really. Quinn didn’t know how to stop the car.

“I hit the wall,” says Quinn, now 11. “And I wanted to do it again.”

Quinn’s driving quickly improved and she went on from driving a club car — a four-cylinder vehicle weighing a few hundred pounds and traveling upwards of 45 mph around a 1/20-mile track — to win four championships in the association before moving up to Bandolero racing on Tucson Speedway’s 3/8-mile track. She’s had success with the larger Outlaw Bandolero vehicles as well. Earlier this month, Quinn took third in points in this year’s Outlaw season, for drivers who are 11 years old and older.

For the first time in Tucson Speedway history, the top three Outlaw Bandolero point leaders — Anika O’Brien, Keirstin Jones and Quinn Davis, who finished in first, second and third place, respectively — are girls.

The Outlaw cars are small but mighty, capable of reaching speeds up to 70 mph .

The sport has obvious dangers. But these girls are taking risks in order to achieve their goals, and they’re tearing it up on the track while slashing stereotypes in what’s historically been a male-dominated sport.(

They’re also forging friendships, supporting each other and providing a solid example of good sportsmanship to drivers of all ages.

All three girls had their struggles during the track’s shortened 2020 season, including crashes and breakdowns, but they stayed focused and stuck together as they drove their way to success.

“I knew my car had it and I had it”

Anika says nothing compares to racing.

“The adrenaline is what makes it fun,” Anika said. “Every time you go on the track, you don’t know what could happen. You have a split-second to decide what to do in a situation.”

The 14-year-old has been driving for five years, but is still two years away from earning her driver’s license, something she calls “not fair.”

Like Keirstin and Quinn, Anika was born into racing. Her dad, Brian O’Brien, began racing stock cars when he was 21 years old. He was Tucson Speedway’s 2016 and 2017 Pro Stock Champion. He also finished second in points in 2018 and again in 2020.()

“Eventually, I want to move up and race against him,” Anika O’Brien said.

Anika began her racing career five years ago in the racetrack’s Bandit division, which is for drivers ages 8 through 11. She’s been a rising star from the start. In her three seasons in the division, she took one Rookie of the Year and two championships before moving up to the Outlaw division.

“Last year, when I moved up to Outlaw, I got Rookie of the Year,” Anika said. “This year, I was hoping for another championship title. That was my goal.”

She has finished in the top five in all four races she’s competed in this year. On Oct. 3, she finished first.

“I knew my car had it and I had it” that day, Anika said.

Next year, Anika will compete in the speedway’s Hobby Stock Division, driving an early 1980s Monte Carlo that she and her dad built earlier this year.

“I raced it once this year, but at a practice the weekend after the first race I crashed into the wall and wrecked it,” Anika said.

The car survived, and Anika’s father drove it to a second-place finish in the Hobby Stock season’s final race last weekend. Anika and her mother, Kristi, proudly watched.()

Anika wants to keep racing for as long as she can. She wants to be a police officer someday, saying she isn’t particularly interested in racing professionally.

“I wouldn’t be interested in going big-time, because it’s not the same, but I do want to continue with short track racing,” Anika said. “My favorite part is the fun of it. Going out there every weekend, you meet a whole bunch of great people.”

“This was a special season”

One of those “great people” is 13-year-old Keirstin Jones, whose racing bloodlines run deep.

Her parents, Dustin and Kelly, competed at the speedway as teenagers and later married. Keirstin Jones’ uncle, Dylan Jones, was crowned Pro Stock season champion last weekend. Her younger brother, Devin, races in the track’s Bandit division.

Keirstin Jones was 8 years old when she got her start in go-karts, She moved up to Bandolero racing three years ago. Last year, during her first season in Outlaws, Keirstin came in third in points.

“My favorite thing is just having fun and winning,” said Keirstin, who has been racing alongside — and against — Anika for the past three years. “This was a special season, because it was all three girls.”

When she’s not busy working on her car and practicing at the track, Keirstin also plays volleyball at Old Vail Middle School.()

After the shortened season, Keirstin is eager to get back on the track next year for a full — and possibly final — season in the Outlaw division. Racing resumed in August following the coronavirus pandemic closures, but with only a few months left in the season, there was only time for three more races.

Keirstin can move up from Outlaw racing when she turns 14, but will likely compete in the full season before “probably” moving up to Thunder Trucks, the same division in which her mom just made her racing return.

Keirstin’s second-place finish was a highlight of her racing career. As far as a career in racing goes, that’s yet to be decided.

“It kind of depends on how everything goes,” Keirstin said.

What’s not up in the air is her love for racing and all that comes with it.

It’s a very competitive sport, but it’s also a nice (way to form) friendships,” Keirstin said. “I’ve made so many friends at the racetrack.”

“It’s not about trophies for me”

While Anika and Keirstin spent last weekend at Tucson Speedway, Quinn was at the Las Vegas Motor Speedway Bullring and Dirt Track, competing in the Bandoleros at INEX Asphalt Nationals.

Quinn loved racing quarter midgets, but at 10, she and her parents realized she was outgrowing the car. She decided she wanted to move over to Bandoleros, and had an impressive first season. Quinn finished fifth in points after only racing half the season, and was named Rookie of the Year.()

“I like to have fun,” Quinn said. “It’s not about the trophies for me. It’s about having fun.”

Like her friends, Quinn was born into racing. Her father, Mark, raced off-road vehicles and motorcycles, and at one point worked as a NASCAR official.

“It’s really surprising that some people say that girls aren’t capable of stuff,” Quinn said. “I do this to make girls have a positive energy and give them inspiration to do this and try other sports as well that boys like to do. We’re not allowed to do baseball, but we can do softball.”

Quinn said the sport allows her to let out her emotions on the track. “They’re really strong at this point because of COVID and not being able to see anyone. You can get them all out on the track,” Quinn said. She added that when “aggressive driving happens on the track, it’s just like, ‘Oh we’re racing now.’”

Quinn is planning to return for another season at Tucson Speedway, and will continue racing in Las Vegas, despite some bad luck at the track, including wrecking her car on the first lap last weekend.

When she’s not helping her dad out with her car, Quinn loves going to cafes and getting her nails done with her mom. She can do both, she says, thanks to the support she receives at home and at the track.

The girl who couldn’t stop her car in her first trip around the track now can’t stop racing.

“I suggest (kids try) racing because everyone is accepting of people and they don’t judge.” Quinn said. “Your friends are supportive no matter what.”

Quinn says she would love to race professionally someday. She rattles off a list of NASCAR drivers, including Brad Keselowski, Noah Gragson and Hailie Deegan, saying, “I want to be like them, but different.

Quinn was 4 years old the first time her dad took her to a race at Tucson Speedway.

On that day, kids were invited onto the track to meet Keselowski and touch his race car, she said.

“I was like, ‘I don’t want to touch the car,” Quinn said. “I want to drive it.”