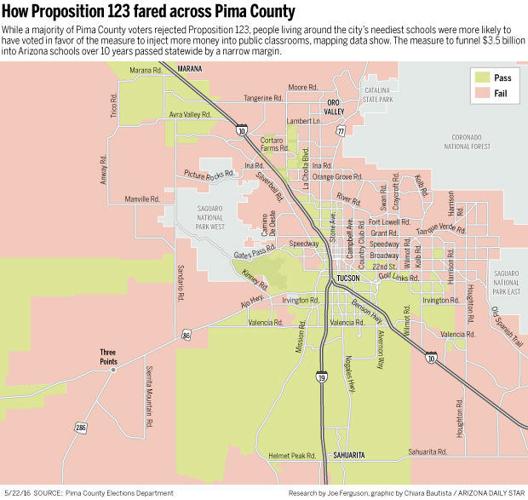

While a majority of Pima County voters rejected Proposition 123, people living around the city’s neediest schools were twice as likely to support the measure to inject more money into public classrooms.

Statewide, voters narrowly approved the plan to pump $3.5 billion into Arizona schools over the next decade. That was also true in parts of southern Tucson, rural Marana, the Flowing Wells area, Green Valley and Sahuarita, an analysis of voting data by the Arizona Daily Star reveals.

Residents in the more affluent areas of Catalina Foothills, Oro Valley and the northeast side opposed the measure, with some areas rejecting the measure by as much as 80 percent.

The voting trend indicates that certain communities feel starved for resources and also illustrates the need for a broader conversation about how a rising tide lifts all boats, said H.T. Sanchez, the leader of Tucson’s largest school district.

“People who have means don’t feel the necessity the way those who do not have means do,” the Tucson Unified School District superintendent said.

For school districts that serve high percentages of families in poverty — like Tucson Unified, Sunnyside and Flowing Wells — generating the kind of money that comes from Prop. 123 is no easy task. Those inner-city districts do not generate as many tax-credit contributions and may not have taxpayer-supported maintenance and operations overrides, Sanchez said.

Pima County was one of only two counties, along with Coconino, to vote against the measure. Nearly 54 percent of Pima County voters rejected Prop. 123, while statewide, it passed with nearly 51 percent of the vote.

The measure settles a years-long lawsuit that several school districts and education groups filed against the state over its failure to adjust education funding for inflation — which voters said they wanted in a ballot measure approved in 2000. Under the new measure, funding will come in part by drawing more money from the state’s land trust. Education already has a distribution rate of 2.5 percent from the trust, but Prop. 123 boosts the amount to 6.9 percent.

What the voting data shows is not surprising to Mary Martinez, president of the Sunnyside Education Association, which advocated for Prop. 123.

Sunnyside, Tucson’s second-largest district, has nearly 17,000 students — 86 percent of whom qualify for free or reduced lunch, an indicator of poverty.

“I think people in areas where socioeconomic (status) is lower tend to be more pro public education and they tend to look at any kind of funding that goes toward public education as a win,” Martinez said.

Polling leading up to the election showed that generally younger, more diverse voters — as well as women and Democrats — were more likely to support additional education funding and Prop. 123, said Pearl Chang Esau, President & CEO of Expect More Arizona.

“I think there’s probably a higher awareness of the urgent need for resources in our schools in those communities, as well as an even more significant impact, if additional funds were to flow into those schools,” she said.

Depending on years of experience, Sunnyside teachers may get a pay hike of $2,000 to $6,000 a year.

“Those that are impacted most by this decision are those who went out and supported it,” said Steve Holmes, Sunnyside’s superintendent.

The deal may not be the best over the long term, he said. But Sunnyside voters felt a “sense of urgency” because the district failed to pass a maintenance and operations budget override last November.

Morgan Abraham, chairman of the Vote No on Prop. 123 committee, said he believed that in legislative districts where lawmakers were more vocal with their opposition, more voters chose to say no.

Also, the “no” campaign was severely outgunned when it came to fundraising, said Abraham, the committee’s chairman. Supporters of the proposition raised more than $5 million with help from the state’s business community. Opponents raised just $16,000 or so.

“We put up a great fight,” Abraham said. “I think we pushed back on the narrative that money trumps everything.”

The reach of the supporters’ campaign was felt on the south-side, where volunteers canvased for the measure, said Ricky Hernandez, chief financial officer at the Pima County Schools Superintendent’s Office.

“When you think about the fact that a lot of these students and their families use education as their only means to come up and out of their communities, the idea of pouring more money into public education sounds like a good plan to them,” said Hernandez, who also lives on the south side.

In the end, the opponents came up short, though the margin was slim.

Pima County school districts stand to gain about $25 million in the first year, Hernandez said. The office is working out the details, but schools could get money as early as late June.

While proponents of Prop. 123 are pleased that the measure passed, Chang Esau of Expect More Arizona says education advocates need to come together for more equity in school funding and better outcomes for students.

“I think this proposition brought people together from across the aisle — the business community, parents and educators — and they had to work together to cross the finish line,” she said.