The number of recorded Border Patrol encounters with migrants at the southern border is higher than ever, but many experts say that doesn’t necessarily mean there are more people coming to the U.S. than ever before.

The high number is misleading for a few reasons, including a high percentage of people crossing more than once and fewer people crossing undetected.

That said, many experts also agree that rising levels of violence and worsening economic and political situations, exacerbated by both the pandemic and in some cases climate change, are driving more people from their homes, from Mexico all the way to Brazil.

The number of times Border Patrol agents encountered migrants in the U.S.-Mexico border region in fiscal year 2021, which wrapped up at the end of September, was the highest on record going back to 1960. There were more than 1.7 million encounters, compared to about 458,000 in 2020, 977,500 in 2019, and 521,000 in 2018, both at ports of entry and on land in between.

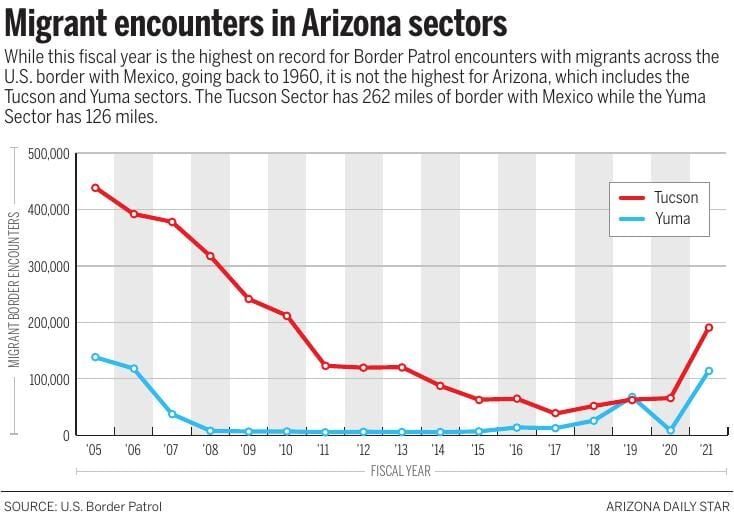

In the Tucson Sector, which covers 262 miles of border from the Yuma County line to the Arizona/New Mexico state line, the number of encounters is the highest since 2010, at about 191,200. There were nearly 66,100 in 2020 and 63,500 in 2019.

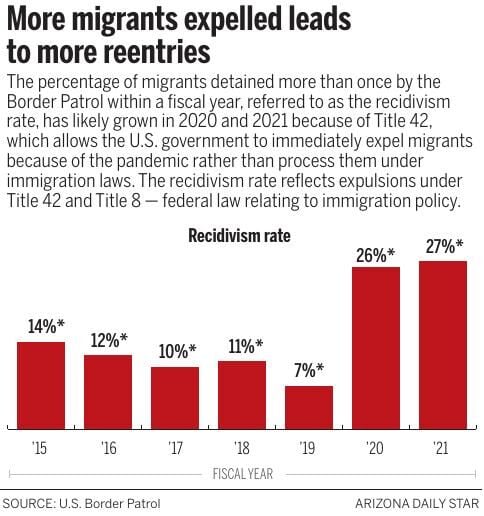

Along with the high number of encounters, there is also a rising percentage of individuals apprehended more than once by the Border Patrol. What officials refer to as the recidivism rate was 27% of encounters in 2021 across the U.S., 26% in 2020 but only 7% in 2019.

The rising recidivism rate has to do with the use of Title 42, a public health policy used since the beginning of the pandemic that allows the federal government to immediately expel migrants from the country without processing them under immigration law.

“This is not the first time we’ve seen large numbers of migrants,” said Customs and Border Protection spokesperson John Mennell. “CBP continues to expel migrants under CDC’s Title 42 authority. The large number of expulsions during the pandemic has contributed to a larger-than-usual number of migrants making multiple border crossing attempts, which means that total encounters somewhat overstate the number of unique individuals arriving at the border.”

Comparisons hard to make

Under Title 42, people are sent directly across the border instead of being sent back to where they originated, making it more likely they will attempt another crossing, said Javier Duran, border studies professor and director of the Confluence Center at the University of Arizona.

As well, because of Title 42 and current immigration practices, fewer people have a chance to enter the immigration process.

“In some ways, the U.S. immigration policy, in practice, has also had an effect by not allowing some of these legal processes to take place,” he said. “To the degree that we’re not, in the United States, able to create orderly processes for these people, not only for asylum but in general, to be able to come to the United States in different capacities, I think we might see an increase in attempts to cross without the proper documents.”

Across the southern border, more than 60% of migrant encounters resulted in an immediate expulsion under Title 42 in 2021. In 2020, 45% of encounters resulted in a Title 42 expulsion, which went into practice in March 2020.

Besides not taking into account the high recidivism rate, the 2021 numbers also don’t account for the fact that the border is more closed now than it’s ever been, said Elizabeth Oglesby, associate professor of Latin American studies at the University of Arizona, who specializes in forced displacement and migration.

“The estimates are that far fewer people are crossing without detection today than, say, 20 years ago,” she said. “The border is largely closed. So we can’t really say that this is a record number of migrants crossing the border. In fact, it’s probably not really anywhere near what it was 20 years ago in terms of people actually getting across the border.”

The U.S. Department of Homeland Security estimated that 2012 was the first year that Border Patrol apprehended a majority of people crossing the border, according to a report from the American Immigration Council. The Border Patrol recorded more than 1.6 million apprehensions in the year 2000 and Homeland Security estimates there were an additional 2.1 million successful unlawful entries.

This year, it’s likely that only about 540,000 migrants were able to enter the country without authorization, according to the Migration Policy Institute, a nonpartisan think tank, based on estimates from Border Patrol figures in recent years.

The high recidivism rate, more detailed data gathering than two decades ago, and the Border Patrol’s capacity in recent years to apprehend a larger number of migrants make a direct comparison to previous years unfeasible, The Migration Policy Institute said in a press release.

Today’s border enforcement strategies include nearly twice as many Border Patrol agents, a greater use of detection technology and a tighter funneling of migrants due to border barriers and enforcement.

Also, the Biden administration being perceived as friendlier than the Trump administration may be another reason more people are migrating now. However, experts say that little has actually changed in immigration policy under the current administration.

Additionally, more people are coming with their entire families and turning themselves into Border Patrol.

“Twenty years ago, you might have had mostly single adults migrating, maybe even going back and forth,” Oglesby said. “Now, the migrant journey is so dangerous. It’s so expensive. The abuses that migrants face in their journey are so intense that that kind of circular migration is really difficult. And so for families to stay together, the whole family has to come.”

Peso devaluation, political dismay

The nationality of migrants and whether they are traveling in a family varies widely across the U.S. border. The Rio Grande Valley Sector, in Texas, had the highest number of encounters at more than 549,000, of which more than 60% involved families or unaccompanied minors.

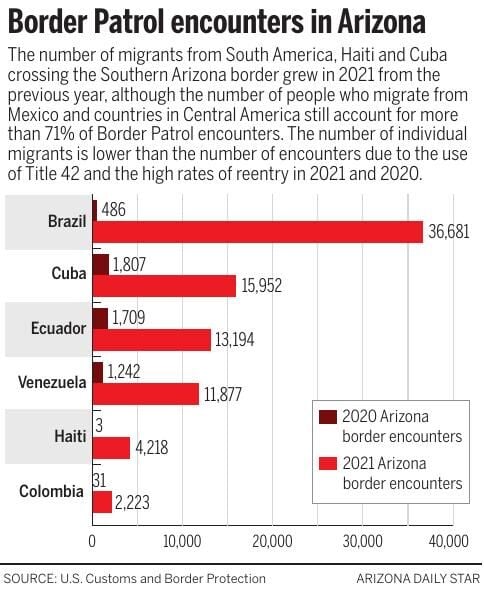

By contrast, in the Tucson Sector, nearly 84% of encounters in 2021 involved single adults, mostly from Mexico or Guatemala. The Yuma Sector saw many more families and people coming from South America, Haiti and Cuba.

Southern Arizona is seeing a resurgence in single adult Mexican migration, said Daniel Martínez, a UA School of Sociology associate professor and co-director of the Binational Migration Institute, specializing in the association between increased border enforcement and migration-related outcomes.

While it’s hard to grasp the breadth of what’s happening with such new data, a few reasons are likely driving this trend, Martínez said. These include the devaluation of the peso over the last decade, causing more economic hardship; disillusionment with Mexico’s political leaders; and ongoing levels of violence.

While the violence isn’t new, its pervasiveness is making it harder for people to flee while remaining in Mexico.

“It’s possible now that we’re starting to see more and more people being displaced by violence, especially as organized crime continues to make its way through most of the country,” Martínez said.

Unlike in the Tucson Sector, more than half of the nearly 114,500 encounters in the Yuma Sector involved families, many of which were from Ecuador, Brazil and Venezuela. The Yuma Sector covers 126 miles of border with Mexico, between the Yuma-Pima County line and the Imperial Sand Dunes in eastern California.

Political and economic distress, violence and natural disasters, which in many cases have been exacerbated by the pandemic, are forcing more people to leave Haiti and countries in South America. As well, the pandemic has made it harder for people to migrate to South American countries or for migrants already established there to stay.

“A lot of people were migrating laterally, or they were going to neighboring countries, or Haitians would go somewhere else in South America,” Oglesby said. “Many countries in South America were absorbing migrants from within the region through things like humanitarian aid work, asylum, temporary work permits. I do think that the pandemic has impacted that.”

Also, the number of encounters with unaccompanied minors on the southern border has increased from about 33,200 in 2020 to nearly 147,000 in 2021.

Unaccompanied minors aren’t immediately expelled under Title 42, and so it’s possible there are more families who are sending their children across the border alone to avoid dangerous conditions in Mexico, Oglesby said.

“You have a lot of people who have been sent back to Mexico under very dangerous conditions,” she said. “It’s a very dangerous and volatile situation in which in many cases parents have self-separated from their children and they have sent their children across the border to keep them safe, to keep them from being recruited into gangs, to keep them from being raped, to keep them from being killed.

“And so, some of what we’re seeing with those numbers of unaccompanied minors is a direct result, again, of our border policies, particularly now this year with Title 42.”