A city park on Tucson’s west side could be renamed in honor of a Chicano activist famously arrested near the site 55 years ago this month.

Salomón Baldenegro helped organize a months-long protest at El Rio Golf Course that eventually led to the creation of Joaquin Murrieta Park.

His fight to bring more city amenities to his predominantly Hispanic neighborhood landed him and his brother in jail, charged with obstruction of justice, on Sept. 19, 1970.

Now a group of west-side residents is pushing to have the park on North Silverbell Road just north of West Speedway named for the 81-year-old.

Raul Ramirez said he launched the naming campaign in April in recognition of Baldenegro’s lifetime of work on behalf of Hispanics.

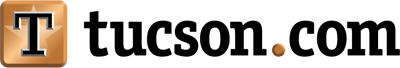

Activist Salomón Baldenegro at a rally in 1978.

“He’s done a lot for the community,” Ramirez said. “It’s not just that park. He’s done a lot.”

The city will be accepting public input on the proposal through Oct. 17. Ramirez hopes to see it come before the City Council for a vote sometime between November and January.

The park has meant a lot to him and his wife, Gloria Jean, who have lived in the neighborhood to the west of it since 1976. The Ramirez children grew up playing there, and the couple has participated in the planning process for improvements to the park over the years.

Another nearby resident involved in the naming effort is Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Frank Sotomayor, who, like Baldenegro, grew up in Barrio Hollywood.

It took Ramirez, Sotomayor and company less than five months to raise the $10,000 fee required by the city to help pay for new signs and other costs associated with a name change.

They have also collected more than 600 petition signatures in support of the idea.

Ari Medina smiles as she rides the playground equipment in June at Joaquin Murrieta Park, 1400 N. Silverbell Road. Some nearby residents are trying to get the park renamed in honor of Chicano activist Salomón Baldenegro, who led protests in 1970 to force the city to build the park.

The park just underwent a $14.4 million renovation — nearly all of it paid for with voter-approved bond funds — including new ballfields, playgrounds, walking paths, restrooms, ramadas, trees and a splash pad. City officials held a grand reopening on May 31.

It was initially called Northwest District Park when it opened in 1973. Its current name is a tribute to Mexican folk hero Joaquin Murrieta, a 19th century vigilante whose highly mythologized actions during the California gold rush are said to have inspired the Legend of Zorro.

Ramirez said the Murrieta name was picked by residents of Barrio Hollywood and Barrio El Rio in the early 1980s and finally added to the park in 1990. At the time, Baldenegro and some of his fellow activists also received a few votes from the neighborhoods.

According to Baldenegro, the 1970 protest began with a broken promise.

A slate of Democratic candidates for City Council told west-side residents they would support the construction of a new park in the neighborhood, but they all had “a very convenient lapse of memory” once they were elected, said Baldenegro, in a 2017 interview by Archive Tucson, the University of Arizona Libraries and Special Collections oral history project.

He and others organized a march on El Rio, where several hundred people ended up occupying the municipal golf course and treating it as their own neighborhood park for the day.

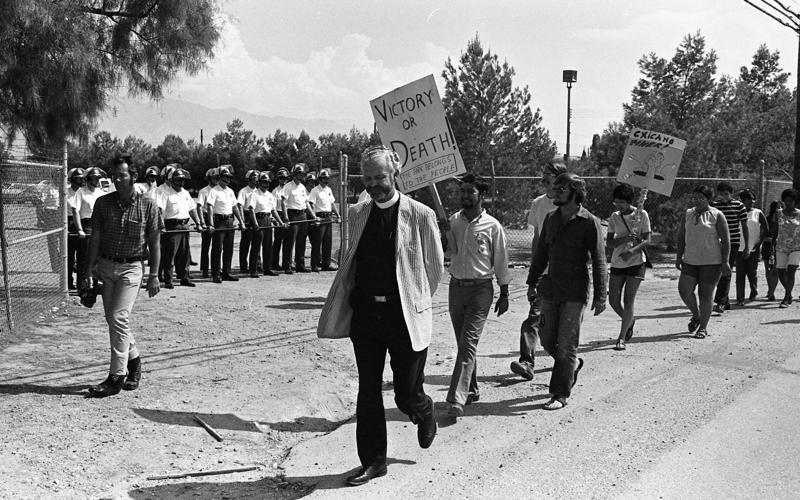

On Aug. 15, 1970, marchers organized by the El Rio Coalition swarmed El Rio Golf Course to demand the city turn the course into a community park.

After a second occupation, Tucson police in riot gear blocked protesters from accessing the grounds, so Baldenegro and company began picketing near the entrance.

Demonstrations were held in front of the golf course at least once a week for months, including one day when the newly formed El Rio Coalition blocked traffic and turned Speedway into a park, complete with picnickers, barbecue grills and kids playing catch.

“We weren’t out to make trouble,” Baldenegro said. “We wanted to make a point.”

The protest leader’s arrest came as he and his brother tried to keep police from taking one of their fellow activists into custody. An officer put Baldenegro in a chokehold — something now strictly prohibited by department regulations — and hauled him away, too.

Neighborhood residents pushing to convert El Rio Golf Course into a community park march in front of Tucson Police officers on Sept. 12, 1970.

He and his brother were later convicted on a reduced charge of using vulgar language but given no additional penalty by a Pima County Superior Court judge who complimented the young activist for trying to do the right thing.

“You paid the price so others could live better,” Judge John P. Collins told him when their case was finally heard in 1972.

By then, city leaders had agreed to build the El Rio Neighborhood Center next to the golf course on West Speedway and a community park on 40 acres of city-owned land nearby.

Protestors march to El Rio Golf Course from Tully Elementary School on August 22, 1970. The community effort to get a park and neighborhood center carved from land dedicated to the golf course led to a major win for Tucson’s burgeoning Chicano rights movement.

Baldenegro, a former administrator and Chicano history teacher at the University of Arizona, said the success of the protests were a defining moment for local Mexican-American politics and what he called the “neighborhood empowerment movement” in Tucson.

“We had made history,” he said. “We had done something that we knew could and would happen but many people didn’t, and that is, we fought city hall and won.”