Supermassive black holes have some of the most voracious appetites in the universe, so astronomers at the University of Arizona and elsewhere can be forgiven for staring at one of them while it eats.

Ongoing observations of the first black hole ever photographed are shedding new light on how these galactic gluttons feed on matter and spit energy back out into space.

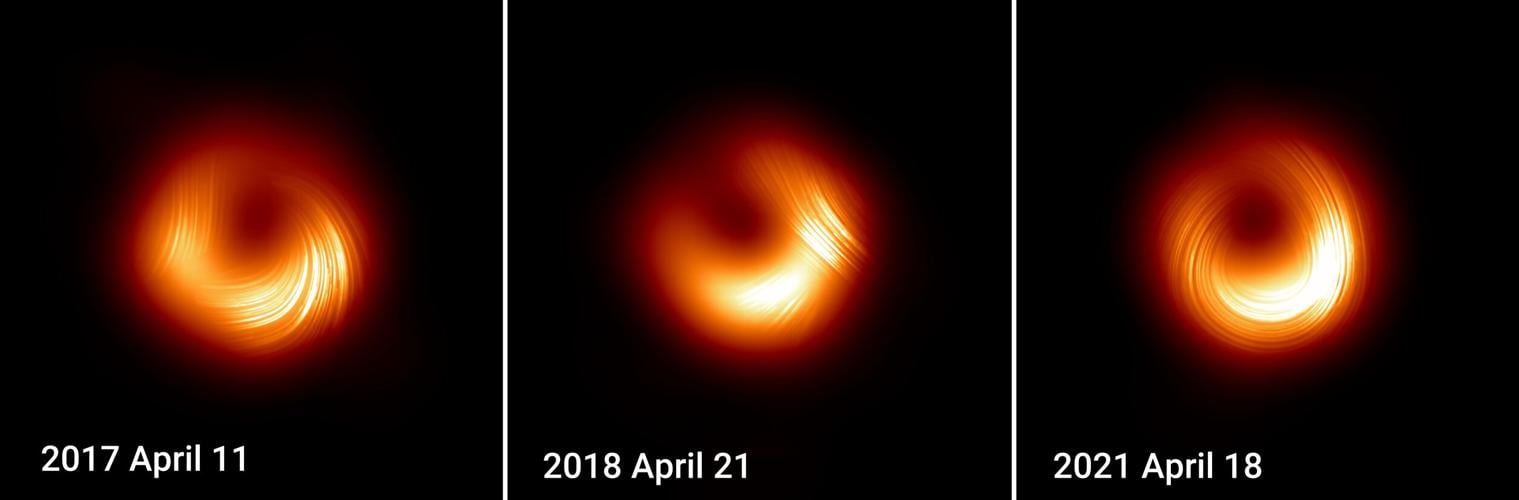

Surprising new images from the Event Horizon Telescope collaboration, which includes scientists and telescopes from the University of Arizona, show how the magnetic fields of supermassive black hole M87* appeared to spiral one direction in 2017, then settle in 2018 before reversing direction in 2021.

By comparing images of the supermassive black hole at the center of the M87 galaxy over the course of four years, researchers managed to chart a dramatic and unexpected change in its magnetic fields, which completely flipped directions between 2017 and 2021.

The international team from the Event Horizon Telescope collaboration also were able to view with unprecedented clarity the jet of superheated particles blasting out at nearly the speed of light from the black hole known as M87*, located in the constellation Virgo about 55 million light-years from Earth.

The findings, published Tuesday in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics, were gathered with the help of numerous U of A astronomers and the university’s Arizona Radio Observatory telescopes on Kitt Peak and Mt. Graham.

Arizona Radio Observatory’s 12-meter dish on Kitt Peak is one of two University of Arizona telescopes used to study black holes as part of the Event Horizon global array.

“Without our persistent observations of M87* year after year, we would not be able to discover this remarkable behavior,” said Boris Georgiev, a postdoctoral fellow at the U of A’s Steward Observatory who contributed to the data processing and interpretation.

Black holes are concentrations of matter so dense that not even light can escape their gravitational pull. The only way to “see” one is by observing the orange ring of superheated gas, known as an accretion disk, as it spins down into the boundless dark of the gravity well.

The Event Horizon Telescope collaboration was conceived in 2009 to study these turbulent and mysterious objects using what amounts to an Earth-sized observatory made from an array of radio telescopes around the world, including the two in Southern Arizona.

EHT scientists made history in 2019 with a fuzzy orange picture of M87* that represented the first-ever direct image of a black hole. Then they followed that up in 2022 with a never-before-seen snapshot of the supermassive black hole churning away at the center of our own Milky Way galaxy.

The University of Arizona’s Submillimeter Telescope on Mount Graham is part of an array of radio observatories around the world used to study black holes as part of the Event Horizon Telescope collaboration.

The U of A’s 12-meter Telescope on Kitt Peak is a recent addition to the EHT array, and it helped provide the enhanced sensitivity needed to see the base of the jet emanating from M87*, a star-eating monster larger than our entire solar system and containing more than 6 billion times the mass of the sun.

“Detecting the jet emission this close to the black hole is like finally seeing the engine that powers these cosmic jets,” said Steward Observatory doctoral student Jasmin Washington, one of the new paper’s co-authors.

Such black hole beams are thought to play a key role in celestial evolution by distributing energy and plasma across thousands or even millions of light-years and directly influencing things like star formation within their host galaxies and beyond. But like a lot of what happens in and around black holes, the origin of the jets is not yet known.

“How this happens and what causes this to happen is still a mystery,” explained Steward Observatory astronomer Chi-Kwan Chan, another of the paper’s co-authors. “Studies like this one help us better understand these processes, which likely involve extremely strong magnetic fields.”

Or maybe it’s just indigestion on a galactic scale.