With Lake Powell sitting a shade less than 35 feet above the level at which Glen Canyon Dam’s generators would be turned off, the agency that markets the dam’s hydropower to 5 million people across the West has no plan for finding replacement power should that worst-case scenario happen.

The agency should have planned sooner for the possibility of a power cutoff, a Western Area Power Administration official told the Star last week.

It didn’t do that, in part, because for years agency officials considered such a prospect ‘academic.’ It was something they used to discuss ‘for fun,’ says an administration environmental specialist.

Now, a federal forecast, released last month, projects a 23% to 27% chance that Powell — the second-largest reservoir in the US, behind Lake Mead — will fall below what authorities call the “minimum power pool” of 3,490 feet during the years 2023 through 2026.

Last week, the lake fell just below 3,525 feet, hitting 3,524.68 on Thursday. Federal and state officials have considered that 3,525 feet offers a buffer, protecting the lake from dropping below 3,490.

Officials of the power administration, commonly called WAPA, which markets the dam’s wholesale electricity supplies to utilities and other regional suppliers, say they have been working hard on producing a plan since last year when it became clear the lake was falling much faster than expected.

But they cannot specify when a plan will be finished nor exactly what issues it will cover.

At the same time, U.S. Bureau of Reclamation and the Upper Colorado River Basin states are exploring several strategies for propping the lake above 3,490 feet as long as possible.

One is the likely prospect for the bureau to soon release water stored in upstream reservoirs in Colorado and Utah to Lake Powell, as it did last year. Another is possibly “re-engineering” the dam to generate power 100 feet below 3,490 feet — the subject of a $2 million, yearlong study the bureau just launched.

But in the meantime, the power administration does not know where and how it would find replacement power for customers who lose power from the dam, if that became necessary.

“Having it below the minimum power pool level used to be academic — we used to discuss it for fun,” said Clayton Palmer, a longtime economist and environmental protection specialist for the agency’s Clayton Palmer, of the agency’s Utah office near Salt Lake City.

The eight massive generators inside the power plant of Glen Canyon Dam. The turbines are fed with water from eight penstocks behind the dam.

“Events have overtaken us, and we should have been planning sooner and more. We didn’t see the lake falling this far this soon,” Palmer said in an interview last week.

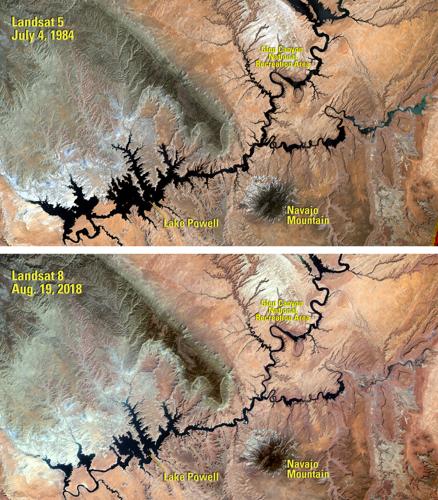

Since March 2021, Powell has dropped nearly 42 feet to its current level. In the two years since March 2020, the lake has dropped a little more than 75 feet from 3,600.71 feet at that time.

The declines, fueled by extreme warm and dry periods triggered in part by long-term, human-caused climate change, have been far more rapid than federal forecasters had previously predicted. In April 2020, for instance, the federal reclamation agency projected Powell would be at roughly 3,613 feet elevation in March 2022. That’s about 88 feet higher than where the lake stands today.

Now, when it comes to the power administration’s planning efforts, “everything is on the table. It could be a plan for power replacement, or to reduce commitments to our customers” to deliver electricity, said Palmer, who has worked for the agency for 35 years. “It could be to reduce our costs by lowering staff levels and maintenance expenses.

“All of those things are being discussed now. We’re talking with Reclamation weekly and with our customers about once a month,” Palmer said.

‘A warning bell, and it’s clamoring’

“We are working on this every day,” said Lisa Meiman, a WAPA spokeswoman. “We want it understood that WAPA is taking this extremely seriously, meeting with the bureau, talking with customers. This is a collaborative effort. We’re not going to resolve this on our own. It’s going to be difficult. It’s going to be a challenge.”

“3,525 is like a warning bell, and it’s clamoring,” Melman said. “It’s meant to be a warning, getting everybody moving in the right direction.’

The historically bad spring-summer runoff into the lake in 2021 was the second-worst in recorded history. It was “not predictable, and accelerated the decline from what we knew three years ago,” Meiman added.

“It is fair to say that, in hindsight, we should have started earlier, but hindsight traps us in the past. We are moving forward with our customers and Reclamation to find solutions that will provide customers as much value from their contracts as possible, in whatever way we can,” she said.

At the same time, officials of the agency can’t say for sure whether they will be able to prevent their customers from losing power or to avoid blackouts or brownouts should Powell drop below the level at which its turbines can run.

But replacing Glen Canyon Dam power is something the agencies are currently planning to avoid, “and we are making plans for replacement power for our customers as much as possible,” Palmer said.

“We have meetings twice a week to talk about how customers would replace power if it would be lost,” said Palmer.

“I know it won’t be easy to do. That’s why we’re working on plans to make it happen,” he said about finding replacement power.

“We hope to hell that we find ways to avoid having Powell going below 3,490, and that we succeed in keeping Powell above 3,490. If we go below 3,490, we sure as hell hope we have everything in place to deal with it,” Palmer said.

Not a sudden concern

But an official with the dam’s biggest Arizona power customer, the Navajo Tribal Utility Authority, said he thinks WAPA should have moved faster to produce a plan for replacement power if Glen Canyon Dam goes dark.

If the dam stops producing power, the tribal agency will have to secure power elsewhere at a possibly much higher cost, said Srinivasa Venigalla, the authority’s deputy general manager for electricity and communications,.

“There’s going to be a concern as a customer that there’s no plan,” Venigalla said last week. “The water levels are going down. This is not suddenly happening, it’s been happening quite some time.”

Top: Landsat image of Lake Powell at its peak water level in 1984. Bottom: Landsat image of Lake Powell in 2018.

“I don’t remember when the last time was when we saw an increase in water levels on the reservoir. In that kind of situation you would expect WAPA to be planning ahead of time instead of waiting till the last minute,” Venigalla said.

The tribal utility authority, which sells power to homes and businesses on the three-state Navajo reservation, gets power from Glen Canyon Dam and nine other dams’ power plants belonging to a network known as the Colorado River Storage Project. It provides about 40% of the power serving the Navajo Reservation, Venigalla said.

The project sells electricity to private utilities, utility cooperatives, tribes, state and federal agencies and other rural power suppliers that operate in six states: Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, Utah, Nevada and Wyoming.

But Glen Canyon Dam furnishes 75% to 85% of the power the entire project sells. That’s enough to serve about 340,000 homes annually at the dam’s current water level, the power administration says.

In Arizona, 42 customers buy power from the entire Colorado River project, led by the Navajo tribal utility. It’s not only Arizona’s single-largest customer of project power, it buys the fifth-largest share purchased by the project’s 132 customers across the West.

The project sold about 426,000 megawatt-hours of power to the tribal utility authority in fiscal year 2019-20, the most recent year for which statistics are available.

The second-biggest Arizona buyer of project power is the Phoenix-area Salt River Project. It gets less than 1% of its total electricity from the Colorado River project and mainly relies on that power to serve peak summertime demand, said Grant Smedley, the utility’s director of resource planning, acquisition and forecasting.

The river storage project also serves 13 irrigation districts in Pinal, Maricopa and Yuma counties. It sells small amounts of power to six Southern Arizona users: Tucson Electric Power, the Tohono O’Odham and Pascua-Yaqui tribes, the city of Safford, the town of Thatcher and the Benson-based Arizona Electric Power Cooperative.

Agreeing with the Navajo Tribe’s Venigalla that WAPA is behind the curve in producing a plan is Ed Gerak, executive director of the non-profit Irrigation and Electrical Distract Association in Arizona. It’s a statewide association of public entities that deliver electricity to agricultural customers throughout the state.

In general, irrigation and electrical districts depend heavily on federal hydropower resources, including Hoover Dam in Arizona and Nevada, Colorado River Storage Project dams, and Parker and Davis dams on the Colorado in Western Arizona, Gerak said. The power is used to operate groundwater wells among other electricity needs.

Last year, the association’s members received 39% of their energy from all the hydropower projects combined, Gerak said.

He said WAPA is “kind of handcuffed legislatively, in what they can and can’t do. Water drives the engine for energy, and water releases through the dams that generate power are determined by the Bureau of Reclamation and the law of river,” he said, referring to laws, court case, regulations and other legal strictures governing river operations.

But “collectively among multiple stakeholders, the feeling is it’s a day late and a dollar short to have a substantial response this late in the game,” Gerak said, adding, “I am concerned about the prospect for short-term pain.”

A boat cruises along Lake Powell near Page on July 31, 2021. Below 3,490 feet of elevation, Lake Powell dips into a zone where the generation of hydropower by water flowing through the Glen Canyon Dam becomes unreliable. At 3,370 feet, the reservoir hits "dead pool," at which point water can no longer be released by gravity from the dam.

‘We will find solutions’

This is not the first time the western power association and its customers have been concerned about Glen Canyon Dam falling low enough to stop generating power.

In 2004, as the lake approached a then-record low level of 3,555 feet during the early stages of the current drought, a WAPA official warned that a cutoff of Glen Canyon Dam power could have serious consequences for customers and the agency.

“If Lake Powell reaches the level where power cannot be produced, it will be unprecedented. That situation would have tremendous impacts to not only power customers but the entire (Colorado River Storage) project. (Its) power could be priced out of the market,” WAPA official Brad Warren warned in a 2004 statement to the Upper Colorado River Commission.

The commission is an interstate agency that is responsible for ensuring “the appropriate allocation of water” from the river to the four Upper Basin states of Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming and that the Upper Basin states meet their Colorado River Compact obligations to deliver water to the Lower Basin states of Arizona, California and Nevada.

Without Glen Canyon Dam power, WAPA would have to pay over $200 million to buy much more expensive power on the open market to meet contractual commitments, Warren said. The administration’s operating fund would run out of money, customers most likely would not buy the power, and The Colorado River Storage Project most likely wouldn’t be able to meet payroll, Warren wrote.

None of this happened. The West turned wetter starting in 2005, and although the drought later accelerated again, the dam did not fall to 3,555 feet again until last year.

At the beginning of 2021, as the water situation was worsening, WAPA started discussing its power rate structure to resolve more immediate challenges that the low water levels were posing to the agency’s power sale revenues and to a broader fund that runs the agency, carries out river-related environmental programs and pays for operation and maintenance work at the project dams, Meiman said.

Once that work was nearly complete early last fall, “we fully focused on longer-term mitigation strategies in the unlikely loss of Glen Canyon Dam hydropower,” Meiman said.

“WAPA has historically worked closely with our customers and the generating agencies to resolve problems, including drought,” Meiman said. “We have worked successfully in the past on these difficult issues, and we will find solutions to this current drought as well.”

Photos: Glen Canyon Dam dedicated in 1966 after years of construction

Glen Canyon Dam

Updated

Glen Canyon Bridge and Glen Canyon Dam during the official dedication of Glen Canyon Dam near Page, Ariz. on Sept. 22, 1966.

Glen Canyon Dam

Updated

Interior Secretary Stewart Udall, right, with Ladybird Johnson during the official dedication of Glen Canyon Dam near Page, Ariz. on Sept. 22, 1966. The Glen Canyon Bridge is in the background.

Glen Canyon Dam

Updated

First Lady Ladybird Johnson with Arizona Gov. Sam Goddard during the official dedication of Glen Canyon Dam near Page, Ariz. on Sept. 22, 1966.

Glen Canyon Dam

Updated

The transformer complex during the official dedication of Glen Canyon Dam near Page, Ariz. on Sept. 22, 1966.

Glen Canyon Dam

Updated

The control room during the official dedication of Glen Canyon Dam near Page, Ariz. on Sept. 22, 1966.

Glen Canyon Dam

Updated

Deep underneath Glen Canyon Dam during the official dedication of Glen Canyon Dam near Page, Ariz. on Sept. 22, 1966.

Glen Canyon Dam

Updated

A giant steel turbine shaft spinning during the official dedication of Glen Canyon Dam near Page, Ariz. on Sept. 22, 1966.

Glen Canyon Dam

Updated

First Lady Ladybird Johnson, center, during the official dedication of Glen Canyon Dam near Page, Ariz. on Sept. 22, 1966.

Glen Canyon Dam

Updated

First Lady Ladybird Johnson during the official dedication of Glen Canyon Dam near Page, Ariz. on Sept. 22, 1966.

Glen Canyon Dam

Updated

Wahweap Marina on Lake Powell during the official dedication of Glen Canyon Dam near Page, Ariz. on Sept. 22, 1966.

Glen Canyon Dam

Updated

Boaters on the new Lake Powell during the official dedication of Glen Canyon Dam near Page, Ariz. on Sept. 22, 1966.

Glen Canyon Dam

Updated

The turbine hall during the official dedication of Glen Canyon Dam near Page, Ariz. on Sept. 22, 1966. The first electricity was generated on September 4, 1964, with the power sent into the regional electric grid through a pair of long-distance transmission lines as far as Phoenix, Arizona and Farmington, New Mexico.[

Glen Canyon Dam

Updated

The eight penstocks that provide water for generation of electricity are revealed on the back of Glen Canyon Dam during the official dedication of Glen Canyon Dam near Page, Ariz. on Sept. 22, 1966.

Glen Canyon Dam

Updated

A man catches some sun during the official dedication of Glen Canyon Dam near Page, Ariz. on Sept. 22, 1966.

Glen Canyon Dam

Updated

Boaters on Lake Powell during the official dedication of Glen Canyon Dam near Page, Ariz. on Sept. 22, 1966.

Glen Canyon Dam

Updated

Boaters on Lake Powell during the official dedication of Glen Canyon Dam near Page, Ariz. on Sept. 22, 1966.

Glen Canyon Dam

Updated

A guest photographs Arizona's newest lake during the official dedication of Glen Canyon Dam near Page, Ariz. on Sept. 22, 1966.

Glen Canyon Dam

Updated

Spectators watch the dignitaries from a distance during the official dedication of Glen Canyon Dam near Page, Ariz. on Sept. 22, 1966.

Glen Canyon Dam

Updated

A boat ride on Lake Powell during the official dedication of Glen Canyon Dam near Page, Ariz. on Sept. 22, 1966.

Glen Canyon Dam

Updated

Wahweap Marina on Lake Powell during the official dedication of Glen Canyon Dam near Page, Ariz. on Sept. 22, 1966.

Glen Canyon Dam

Updated

Photograph of a bend in Glen Canyon of the Colorado River, Grand Canyon, ca.1898. The towering nearly-vertical rocky canyon walls loom over the placid river. The canyon rim is visible in the distance. A rocky embankment forms the shore on one side of the river. Two men row small boats on the river.

Glen Canyon Dam

Updated

Glen Canyon damsite from the air in November 1957, prior to construction of the Glen Canyon Bridge

Glen Canyon Dam

Updated

Aerial view of Glen Canyon Dam during construction - 1962

Glen Canyon Dam

Updated

Construction of Glen Canyon Dam in 1963.

Glen Canyon Dam

Updated

Lake Powell filling underway, 1965

Glen Canyon Dam, bridge, construction

Updated

Steelworkers sit on the steel span for Glen Canyon bridge under construction high above the Colorado River in the late 1950s.

Glen Canyon Dam, bridge, construction

Updated

The bridge span emerges from the anchorage in the wall of Glen Canyon just west of the dam site under construction, late 1950s.

Glen Canyon Dam, bridge, construction

Updated

Heavy equipment moving rock at Glen Canyon Dam site, late 1950s.

Glen Canyon Dam, bridge, construction

Updated

Dozens of survey marks dot the wall of Glen Canyon at the site of the dam in the late 1950s.

Glen Canyon

Updated

Bend in Glen Canyon of the Colorado River, Grand Canyon, ca.1898. Photographer: George Wharton James