The phrase “lived experience” sounds redundant when you think about it.

Of course, any experience you’ve had, you’ve lived.

But really, in many cases, the phrase isn’t so much redundant as it is missing a word — “hard,” as in “hard-lived experience.”

Arizona Daily Star columnist Tim Steller

That’s what the people who staff the Transition Center outside the Pima County jail bring to their jobs — hard-lived experience. And they try to impart hard-won knowledge to the people who pass through, many of them fresh out of jail.

The Transition Center has been operating since summer 2023, when Pima County opened it at 1204 W. Silverlake, just outside the Pima County Adult Detention Center — the jail. It’s staffed now by five “justice navigators,” with one position still open. They help whoever walks in to overcome the next obstacles they’re facing.

That might mean going to detox, getting a phone, exploring treatment options, resolving a warrant or finding a place to stay.

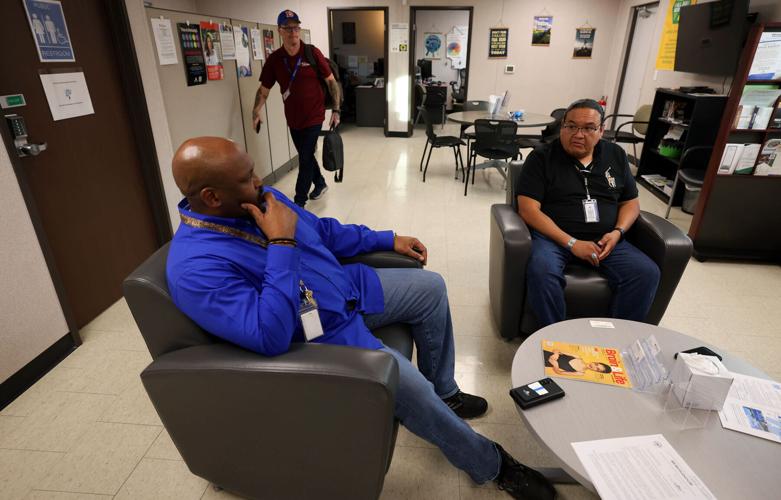

Doyle Morrison, left, and Bruce Donahue, a justice navigator, sit inside Pima County’s Transition Center, which opened in the summer of 2023 just outside the jail.

Staffing the place, though, required “a shift from normal operating procedures,” said Kate Vesely, the county’s director of justice services. The hard-lived experiences of these staffers mean that many of them have been in and out of jail, most have felony convictions, some have substance use disorder or serious mental illness — not normally qualifications for a county job.

“The whole purpose is to hire individuals with lived experience,” said Doyle Morrison, 56, who manages the center. “That is what a peer is, someone with lived experience.”

This local experiment in peer support appears to be working. County Administrator Jan Lesher reported in November that among the more than 1,100 people served in the first year of the center, fewer than 10% were rearrested within 30 days. That compares to 27% in a control group.

When the clients come in and find support from people who’ve been through it all, that’s the “secret sauce,” Morrison said.

“Everybody in here is a peer,” Morrison said. “It disarms them and makes them feel safe.”

Four of the people who staff the center told him how they try to use their experience to help people in troubled moments take positive steps.

‘I take pride in what I do’

Rosa Lamadrid has a pointed way of reaching the women she sees.

“I tell them, I guarantee I’ve been arrested more times than you have,” Lamadrid said.

She estimates she’s been released from the jail outside of which she now works hundreds of times.

Lamadrid

“There’s nothing these women have went through that I can’t share something with them about,” she said.

Lamadrid, 42, grew up in South Tucson and started using drugs with her mother at age 14, she said. The next nearly 20 years were very rough, with a couple of periods of sobriety and management of her serious mental illness.

“To be honest, I’ve OD’d multiple times,” she said. “I’ve relapsed over and over.”

“It has been a very sad, traumatic, but also a very powerful experience that has made me who I am today,” she said.

Somehow, there came a time nine years ago when sobriety stuck. Most of all, Lamadrid said, “I was just tired” and “really, really ready.”

But also, she wanted to help her family through its struggles and simply support herself. She was fortunate that she had inherited her father’s home on the Pascua Yaqui Reservation.

Her first job was at a Dollar Tree, she said. In fact, some dollar stores have been good places to start for people with a felony record and a desire to move forward, she said.

She went on to work at sober living homes and other places before ending up at the Crisis Response Center. She was recruited from there to join the Transition Center.

“I take pride in what I do now, because an individual could come in, and the majority of the time, I think very, very rarely we’re unable to place them in, like, a detox or rehab or something like that.”

The exception is housing — sometimes shelter space is scarce. Still, she said, for people in the situation she used to be in, “Now there are a lot more opportunities.”

‘In the real thick of it’

Todd Auge had been banging around Cochise County, getting high and getting in trouble, for years when his moment of truth came. He had planned to skip out on a ride to Tucson to go to treatment, he said, but instead, he walked a couple of miles to a friend’s house and made it here, to the home of that friend’s uncle.

Once here, though, he went to the Salvation Army and dropped dirty — he had smoked meth too recently. The man at their intake told him, Auge recalled, “I want you to go home and drink water. I’ll save your bed for a few days.”

Auge

Amazingly, he did it. Auge didn’t go out and get high — he stayed in and drank water, and after that, went to treatment at the Salvation Army. He’s been sober more than eight years.

Auge, now 53, got trained in peer support and ended up working in wind power before winding up back in jail — this time working for a social service agency inside.

“I was working in the pit in there, so I got a real good crash course in short term case management,” he said. “You know, helping folks out in the real thick of it — fresh.”

Auge made his way outside the jail, to the Transition Center, by applying to the city of Tucson, which funds two of the positions in the center.

What he encounters most is what you’d expect — people addicted to fentanyl. Sometimes, what allows him to connect to the people he sees as simple as the tattoos on his arms.

What “many people don’t get is we don’t give a (damn) about ourselves in here,” Auge said, referring to people in jail and on drugs. “My big thing is getting them to the next place where they can care about themselves a little bit.”

Helping Indigenous population

When Bruce Donahue grew up in the southern part of the Tohono O’odham Nation, moving drugs and people “was the only homegrown business we had,” he said. “You know, it was the way that people were able to put food on the table.”

When he was finally arrested, Donahue recalled, the DEA considered him the biggest cocaine trafficker on the reservation. At the time, it was a source of pride.

“When I got clean, it became a source of a lot of shame and a lot of guilt,” Donahue said. “Working a 12-step program and really getting back into my culture helped me work out some of those things, and I continue to work on those things.”

Donahue, 48, is one of the original staffers who joined the Transition Center in summer 2023.

“I like to believe that I am able to work with anybody, but I do have a special interest in working with the indigenous population,” he said.

He told of one 26-year-old who came through the Transition Center out of jail, got a phone and other help, but later relapsed. Donahue helped hook him up with a new 90-day stay in treatment, but he had also violated parole.

The real challenge was going to be dealing with his parole officer. Donahue accompanied the young man to the parole appointment, helped get his warrant quashed and his parole reinstated.

“We’ve really evolved in the time that we’ve been here to meeting individuals where they’re at,” he said.

‘Attitudes are changing’

You wouldn’t be finding Morrison, the manager, in this modular building if it weren’t for an FBI sting operation. Morrison, then a sergeant in the National Guard, was caught up in Operation Lively Green, the 2002-2004 operation in which undercover federal agents paid military service members, corrections officers and other public employees in Southern Arizona to move drug loads.

He had been a well-respected and decorated non-commissioned officer who even participated in a counter-narcotics task force before he got caught playing a minor role in the operation.

Morrison doesn’t share the experiences of life on the streets that many of his coworkers have had. But he’s got the bitter experience of losing the life he once had and working to recover the productive life he once lived.

And now he, like the others at the Transition Center, is seeing more public openness to helping people despite their transgressions, or because of their afflictions. The public is more accepting of that hard-lived experience, if people will take a step to change.

“Minds and attitudes are changing because this opioid epidemic crosses every boundary,” Morrison said. “It touches everybody.”

Too bad it’s taken that for attitudes to change, but a good thing the Transition Center, with its experienced staff, is one of the outcomes.