Ted Cooke, the former Central Arizona Project general manager whose nomination to head the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation was scuttled by congressional opposition, says the four Upper Colorado River Basin states will have to accept cuts in their water use to make a seven-state deal work to ensure the river’s future.

If they don’t, and something isn’t done to curb river water use quickly, he says a “catastrophe” could occur as soon as next year in which Lake Powell’s water level would be too low for Glen Canyon Dam to generate power for 13 million electricity customers, and the U.S. would be unable to release river water from Lake Powell or Lake Mead for use by the Lower Basin states of Arizona, California and Nevada.

Cooke does agree with the Upper Basin states’ view that the Lower Basin states’ overuse of river water has drained lakes Mead and Powell. But he said the Upper Basin’s position is that it shouldn’t have to take cuts now, because it’s already suffering from lack of precipitation, is weak and not very valid.

That issue — the Upper Basin states’ unwillingness to commit to any mandatory water conservation measures — has been a key sticking point blocking a seven-state agreement to curb the overuse of water. The Upper Basin states are Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming.

The Colorado River cuts through Black Canyon near White Hills, Arizona. If something isn’t done quickly to reduce the overuse of the river’s water, the U.S. — as soon as next year — might not be able to release river water from Lake Powell or Lake Mead for use by Arizona, California and Nevada, retired CAP general manager Ted Cooke says.

Cooke also said one reason he thinks his nomination as Reclamation commissioner failed was not that he would be biased in favor of the Lower Basin — he insists that’s inaccurate — but because “I knew too much,” particularly what he saw as the weaknesses of the Upper Basin position that it shouldn’t take any cuts.

President Donald Trump withdrew Cooke’s nomination in mid-September after opposition surfaced among Upper Basin state officials.

On Wednesday, Cooke spared few sides of the combative Colorado River issue from criticism in an interview with the Arizona Daily Star, led by how he would have tackled the prolonged dispute among the states over how to curb their chronic overuse of river water had he become commissioner.

Cooke, who is 70, is one of the very few public figures who has been intimately involved in Colorado River issues who now freely and publicly expresses his views on them. Most officials and others who have participated in negotiations over river management have stayed mostly mum, largely to protect the confidentiality of the negotiations.

Cooke retired in January 2023 from the CAP, the canal system that brings Colorado River water to Tucson and Phoenix for drinking and to central Arizona farms.

He hasn’t participated in river negotiations since leaving CAP, but as general manager, he and Arizona Department of Water Resources Director Tom Buschatzke were partners in dealing with river issues, most notably their successful effort in 2019 to create a Drought Contingency Plan to impose the first water use curbs for Arizona, Nevada and California.

In the Star interview, Cooke also said:

- If he’d gotten the Reclamation job, he would have tried to arbitrate, not mediate, the dispute by forcing all the various state officials to first put themselves in their adversaries’ shoes, to see if that helped them reach consensus. If that failed to reach agreement, he would be willing to impose a solution on the seven states, something Reclamation has been unwilling to do.

- The chances of litigation erupting over the river are now at 50-50 and getting worse as time drags on without an agreement.

Cooke spoke the day after the U.S. Interior Department and basin state officials announced they hadn’t met the federal government’s Nov. 11 deadline for reaching an agreement, but would continue to talk because “collective progress has been made.”

Ted Cooke, far left, Central Arizona Project board member Lisa Atkins and CAP Board President Terry Goddard at Hoover Dam. Cooke, whose nomination to head the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation was scuttled by Upper Colorado River Basin opposition, tells the Arizona Daily Star the four Upper Basin states will have to accept cuts in their water use to make a seven-state deal work to ensure the river’s future.

Here are some questions and answers from the interview:

Q: If you had been confirmed as Reclamation Commissioner, what would you do now to get the seven states to agree on a long-term solution to the river’s chronic deficits? Would you impose a solution now, or try to broker a deal with the two basins as Arizona Gov. Katie Hobbs has requested of Interior?

A: I’m not an insider. I obviously don’t know the details. I’m giving Reclamation the benefit of the doubt that there’s a reason for their reluctance to do something, other than their habitual reluctance that they don’t want to do anything hard or set a precedent. They may not have one. They may just be unwilling to do that.

It is difficult for me to say I would definitely impose a plan. ... Broker — it’s kind of difficult to say what it means. There is more Reclamation can do. If they are willing to say, “Your time is up and we’re going to do this,” that’s a stronger position than brokering. I would call it arbitration. There’s only one answer on things.

The (computer) modeling shows that reductions in use need to be taken by the two basins. Both the Upper and Lower Basin proposals from last spring are pretty close in that regard.

There can only be one interpretation that makes sense of how to interpret Article 3 of the Colorado River Compact (which says the Upper Basin will not cause the flow of the river at Lee Ferry — just downstream of Glen Canyon Dam — to be depleted below 75 million acre-feet total over a decade). They (Reclamation officials) don’t want to take sides on that. On some things, you have to take sides. Only one perspective can be correct at that time. It means this is the one we’re going to go with.

Q: What do you think is the difference between arbitrating the dispute and imposing a solution?

A: The latter is saying, “Here’s what we are going to do and we’ll do it.” Arbitration is to introduce a different perspective, and to ask each side how they think about how they could implement a plan.

The arguments being made on all the sticking points have not moved the needle. It’s just like point of view A vs. point of view B; I would like to ask people with point of view A, “Pretend you passionately believe point of view B, and how would you go about addressing this issue?” The same for people with point of view B.

The U.S. needs to have a plan. You need to find a way to move parties toward that. Arbitration is one way to do that. Put yourself in the other guy’s shoes.

Q: So would you impose a solution if that didn’t work?

A: My comments are intended to imply the outcome could be an imposition if the parties don’t make some movement. That has to stay on the table till it’s replaced with something better.

Cooke

Q: What’s your reaction to the inability of Interior and the seven basin states to reach agreement by the Nov. 11 deadline?

A: It’s a disappointing outcome that they didn’t have anything. I don’t think it was much of a surprise to anyone. Unfortunately, this is sort of a pattern we’ve seen for some time in regard to river negotiations, with respect to the basin states and Reclamation. There’s a deadline, it comes and goes. Sometimes, something less than what is needed is accepted. Everyone pats each other on the back and says, “Well done, well done.”

As you know, leading up to this deadline, there were rumors there would be only a five-year plan, or maybe only the Lower Basin states. If you look back to proposals from the Upper Basin and the Lower Basin, submitted to Interior in May 2024, those were pretty lofty goals, how much water needed to be saved, and how much water elevation do we need to protect?

There’s always a danger a deadline passes. Reclamation doesn’t do the implied threat. Or, we accept what is needed. The former happened, the deadline was passed, nothing happened and everyone agrees to keep working together, although we’ve been working together 1.5 years at least and the core points, they’ve not gotten closer on those things.

I don’t know what to expect from more time beyond less time to do everything else that needs to happen — like going through the whole NEPA (National Environmental Policy Act) process. There needs to be an EIS (environmental impact statement). There needs to be a public process. There needs to be a Record of Decision, reviewed by the public, as well.

Q: I know you don’t have a direct pipeline to the negotiators, but do you think it’s possible they’re simply keeping the talks going because they don’t want the feds to step in and impose their own deal? Or do you think there is real progress that simply needs more time to fully flower into an agreement? Or are they just trying to save face?

A: Saving face might be part of the equation. When the Nov. 11 deadline was pronounced back in June by (Acting Reclamation Commissioner) Scott Cameron, that was one point on the timeline. By the end of the year, Reclamation would begin the process with a draft EIS, on Feb. 14, 2026, is the deadline for the seven states to flesh out their Nov. 11 deal and have a final proposal in late spring or early summer with a final EIS. What happens between February and late May or so, that’s when the public process takes place, where they get (public) comments. Then in the summer, Reclamation prepares its Record of Decision.

Nov. 11 was just the first deadline. Why do people feel comfortable just blowing through this deadline? They’re not done. They’re no closer on key issues, even though there are claims of progress, or whatever adjective they used. In my opinion, the progress made is on satellite or ancillary issues, like how salinity is going to work if there is less water in the river. This is not a major deal point that is going to stand on its own. It needs to happen sometime, but it’s a distraction from making progress on the main things.

Q: But don’t we have more time before the current guidelines for managing the reservoirs expire next September?

A: If the period of time between Nov. 11 and Feb. 14 next year is a period in which the seven state’s proposal goes from preliminary to final, and we say we can keep working on it ... To me, it’s like saying ‘I have all semester I can get ready for my final, so I’ll play golf for two or three months.’ I know they aren’t playing golf. They’re working their assess off, but they’re going around and around going through past history. You know, “You told me I was ugly, you have to take that back before I will talk to you.”

They say “no, we didn’t miss the deadline. We collectively believe enough progress has been made we can continue to move on.” What a bunch of malarkey. It’s double-talk.

Those deadlines have to mean something. To pass one means less time to do what needs to be done.

Q: So do the delay or delays reduce the chance of a workable long-term deal by the final deadline for the negotiations of Sept. 30, 2026?

A: Of course, that’s my whole point. You’re taking longer to do the work assigned to the earlier deadlines. That is not a good sign you are going to to be able to get the harder work done by the later deadlines. There is a hard stop on Sept. 30, 2026. The 2007 guidelines (for operating the reservoirs) expire on Sept. 30, and they are no longer operational.

Q: Could the states and Interior extend the deadline another year?

A: I suppose that could happen, and maybe that is what happens. To me, that falls within the category of settling for a lesser outcome.

The water reductions contained in the 2007 guidelines, the Drought Contingency Plan of 2019 and (later plans) are not enough to sustain us even for one year.

Q: What do you think the odds are of this going to litigation? I’ve heard some people say it’s a 95% chance now.

A: I think it’s pretty substantial, at least 50-50. The more time that goes by and it gets worse, there’s a greater likelihood there will have to more of an imposition of a solution by Reclamation than a compromise among the states. There are more opportunities for hasty decisions that aren’t completely researched ahead of time. It’s bad and it’s getting worse.

Q: Why do you believe the Upper Basin states should have to take cuts in their water use? And what do you think of the arguments both basins have made — the Upper Basin states saying they shouldn’t have to take any cuts and the Lower Basin states saying the cuts should be shared by both basins?

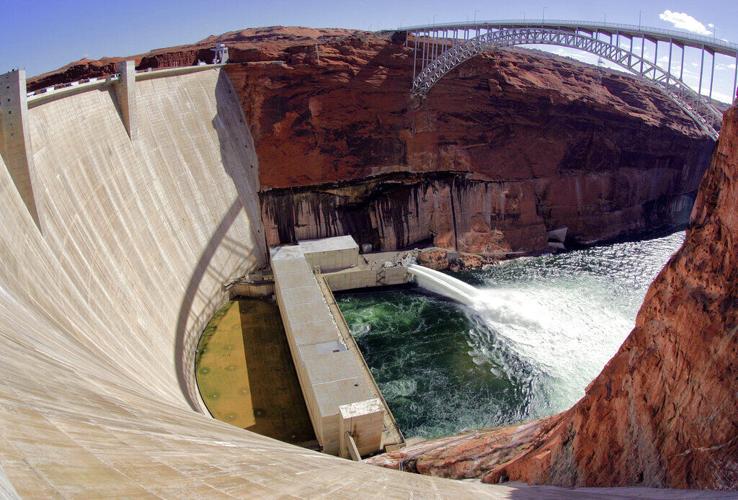

Glen Canyon Dam on the Colorado River near Page, Arizona. If something isn’t done to quickly curb Colorado River water use, retired CAP official Ted Cooke says a “catastrophe” could occur as soon as next year in which Lake Powell’s water level would be too low for Glen Canyon Dam to generate power for 13 million electricity customers in the Western U.S.

A: I believe they have to take something in the Upper Basin, not just because that seems like the right thing to do or it’s fair. Their justifications of why they shouldn’t have to take anything don’t support that conclusion. This is an educated opinion, not just shooting from the hip.

I think the Upper Basin has weak arguments in some areas, as does the Lower Basin. The Upper Basin’s are relatively weaker, particularly when it comes to two things around which this impasse revolves.

One of them is (their) contention that the hydrologic shortage that the Upper Basin takes every year, that out of their 7.5 million acre-feet appointment for the last 20 years at least, there’s been a hydrologic shortage of water that has never materialized, means they shouldn’t have to take more cuts.

I’m sorry for them. It’s unfortunate. They haven’t been able to develop that supply. The water is just not there. But for them to use the word shortage, which is typically used for mandatory reductions from a historical level of use, that’s not what they been taking.

If they’re reducing from their existing level of use that’s a reduction. Water that never did fall from the sky is not a shortage. It’s disingenuous to argue as such.

Q: What about the Lower Basin?

A: The Upper Basin does have a legitimate beef with claims of Lower Basin overuse. For a long time, the Lower Basin, even after it became apparent 25-30 years ago about the so-called structural deficit, did not do anything about it. It did not take steps to offset their evaporation and (other) water losses. (The structural deficit is an estimated, chronic 1.5 million acre-foot gap between Lower Basin water use and supply that would exist even if climate change wasn’t depleting river flows.)

They in the Upper Basin believe overuse is what has drained Lake Powell and Lake Mead. This is true. But we’re not balancing the books on the back of new (operating) guidelines. We’re not putting that water back, not enough to make up for every past grievance for sure. What’s the point? We’re at where we’re at.

We’re using a certain amount of water. We have to use less. We have to be able to find a way to allocate it without saying you did this and you owe me that. There’s a lot of that going around. It’s not helpful. Even though the Upper Basin has a legitimate (grievance) with overuse by the Lower Basin, that does not justify the Upper Basin’s being disingenuous with them saying they’ve been taking shortages for decades, and trying to equate that with overuse. It’s not to balance the books. It’s not a contest as to who saves more.

Q: Why do you think your nomination for Reclamation commissioner was killed? Some Upper Basin senators and other officials felt you are biased in favor of the Lower Basin. Are you bitter about how it turned out?

A: I’m unhappy, not bitter. It continues to be hard for me to say I don’t have a resentment. I’m insulted by the accusation that I would not be able to act without bias. I don’t deserve that. I don’t know if anybody in my position or in any one of seven basin states deserves that accusation. Right out of the block, I don’t really think that is legitimate.

I think what they were concerned about is I knew too much. They wouldn’t be able to get away with some of these arguments. They would say, “See, we told you he couldn’t be fair, he’s already made up his mind. He’s not even involved in the process and he’s saying we were wrong. We knew this was going to happen.”

Ted thinks that’s not the real reason. Their fear was that Ted would shine light on some of these arguments and tell the truth on some of these points of contention. Ted believes what they were really afraid of is that he understands their points of view and weaknesses, and he would tell the truth about those weaknesses and expose them.

Q: This past week, you posted on LinkedIn, “The river doesn’t have time for failure or another stop-gap, kick-the-can-down-the-road plan. At this moment, the available active storage in Lake Powell and Lake Mead (water stored in the reservoirs that can be easily removed) is less than 7 million acre-feet, less than a single year’s use by the Lower Basin and Mexico, after considering the water that may not be reliably available. This is a ‘virtual run of the River’ situation. We are only one bad winter away (like the one in winter 2025) from catastrophe.”

What do you mean by catastrophe?

A: It could include not being able to deliver water out of Lake Mead and Lake Powell when ordered, possibly not at all, in 2027. What happens if you use it up in 2026, you had a crappy winter, and you don’t replace what you use? You’re stuck with having lakes at lower levels; we’re taking out more than what’s coming from snowpack. Power generation at Glen Canyon Dam could be completely or partially lost. Power generation at Hoover (Dam) could be partially curtailed.

Longtime Arizona Daily Star reporter Tony Davis talks about the Colorado River system being "on the edge of collapse" and what it could mean for Arizona.