What did the soldiers at the Tucson Presidio have in common with famous figures like George Washington and Paul Revere?

More than you might think, according to the Daughters of the American Revolution, which is now recognizing these other, lesser-known patriots from the far-flung desert outpost on the Spanish frontier.

As Washington marched the Continental Army toward victory over the British, the soldiers and settlers at the newly built Presidio were doing their part to support American independence, one silver coin at a time.

By royal decree on Aug. 17, 1780, Spain’s King Charles III called on each of his loyal subjects in America to donate to the war effort against “the insulting tyranny of the English nation.” The requested “donativo” was one to two pesos, depending on a person’s ancestry and social class.

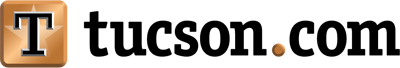

The garrison at San Agustín del Tucson ended up contributing a total of 459 silver pesos to the cause — no small gift at a time when a side of beef cost about four pesos and a high-quality riding horse cost about seven.

As Catholic priest and University of Arizona historian Kieran McCarty observed in his 1976 book “Desert Documentary”: “Tucson’s contribution was remarkably high, considering that it was an infant settlement, and more than doubled what was taken up in the wealthy capital at Arizbe.”

As a result of the Presidio’s generosity, the Daughters of the American Revolution decided earlier this year to officially declare the men who were posted there as “Spanish patriots.”

The Arizona State Society of the DAR will hold a ceremony downtown on Oct. 25 to dedicate a new historical marker to that effect on Church Avenue, just outside the Tucson Presidio Museum.

“I think it’s amazing that Arizona has this small part of the American Revolution,” said Sarah Ziker, DAR’s state regent for Arizona. “It’s exciting to celebrate it.”

Patriotic proof

So far, the 135-year-old historical service organization has identified 13 individuals who served at the Presidio at the time the donativos were collected. The descendants of those soldiers are now eligible for membership in the DAR, which only admits women with proven lineage to those who served the colonial cause during the Revolution.

“We are working with some of the descendants of the Presidio on their DAR applications, because they have to prove each link from that soldier to them,” Ziker said. “There’s about eight to nine generations, and you have to prove each link.”

Such research is complicated by the region’s complex history, which involves documents recorded in two languages and potentially archived in at least three different countries on two continents.

Monica Smith poses with her sons, Chris Herrera, left, and Jeff Herrera, right, during a 2018 ceremony in Tubac honoring their 18th century ancestor Juan Manuel Ortega.

“In DAR, we have a lot of genealogists who are really good at this kind of thing, but this is a whole different puzzle,” said Ziker, who has documented 34 patriots in her own family tree, including an apprentice blacksmith who took part in the Boston Tea Party at the age of 15.

In the end, the Daughters in Arizona had to petition the national office to acknowledge the patriotic service of those posted to the Presidio based on circumstantial evidence alone.

“We’ve never been able to find the list of those Presidio soldiers who gave the donativo,” Ziker said. “But we know these 13 soldiers were there during the payments, so (by) inference or indirect evidence, we’ve proven that these 13 are eligible to be patriots.”

That baker’s dozen of names alone could represent hundreds or even thousands of potential new members for DAR, which already boasts 44 chapters in Arizona, including four in the Tucson area.

A royal ally

The Presidio San Agustín del Tucson was founded on Aug. 20, 1775, four months after Paul Revere’s famous midnight ride on the other side of the continent.

The adobe walls were still being built around the fortress when the Spanish king issued his call for donations in 1780.

There’s some debate about how voluntary the donativos might have been.

In “Desert Documentary,” McCarty writes that those collecting for the king were under strict instructions not to order or coerce soldiers to contribute.

But Ziker said her understanding is that it was “really kind of a tax, because they had to pay it. There wasn’t really an option.”

Members of the Tucson Presidio garrison, dressed in period costume, fire their muskets toward downtown as part of the city’s birthday celebration in 2008.

DAR has also begun enrolling the descendants of Spanish soldiers from colonial-era forts in present-day New Mexico and California, including some from which original rosters have been found detailing the individual donations each man made.

Of course, Spain provided far more than financial support to the American rebellion. Spanish troops and naval vessels drove the British out of Florida and the Gulf of Mexico and helped keep supplies flowing to the colonies from the south and along the Mississippi River.

The DAR’s new historical marker downtown is part of a larger campaign by the group and the William G. Pomeroy Foundation to place 22 blue and gold plaques at Revolutionary War sites around the country ahead of next year’s 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence.

Unsurprisingly, perhaps, the marker at the Presidio is the only one in Arizona and one of just three located west of the Mississippi.

“It is such a great little piece of history, and we’re just thrilled that we even got permission to place this plaque,” Ziker said. “What a great way to highlight Arizona and our one little connection.”

Sons also rise

Not to be outdone by the Daughters, the Sons of the American Revolution is in the midst of its own countrywide push to recognize more patriotic people and places in honor of the nation’s 250th birthday.

Though they sound like literal siblings, the Sons and the Daughters are separate nonprofits with their own eligibility rules and standards for proving family lineage.

A new Daughters of the American Revolution plaque at the Presidio San Agustín del Tucsón, 196 N Court Ave.

Tucson native Dr. Rudy Byrd previously served as SAR’s national surgeon general and is now the secretary for the group’s local chapter. The family practitioner and amateur historian also volunteers as a costumed reenactor at the Presidio Museum, the Fort Lowell Museum and as a member of SAR’s color guard.

Byrd

“It means I get to wear wool in summer,” he said. “What fun is that?”

Byrd said the Sons has established America-at-250 commemorative committees in all 50 states, but the one in Arizona hasn’t found much to do so far.

“The basic problem, of course, is how do we tie Arizona into the Revolution? We’re in what I call Spanish Siberia. We’re the furthest thing away from Spain, and we’re a part of Spain; we’re not a part of the United States out here. How do we tie in?” Byrd said.

The answer, of course, is the Presidio and its 459 silver pesos.

Byrd said the local SAR chapter is hoping to celebrate that local link to American independence next year by placing a marker at the site of the original Presidio cemetery, near Church Avenue and Alameda Street. He already has the perfect spot picked out on the southeast corner of the intersection, right next to the historic Pima County Courthouse, though he said he still needs county officials to sign off on the idea.

“That ties Tucson into the American Revolution. That ties Arizona into the American Revolution,” said Byrd, whose ancestry includes at least 20 patriots. “We have just as much claim, historically, as Philadelphia, Boston, Charleston and the places back East.”

First daughter

Tucsonan Monica Smith hopes to become one of the first Presidio descendants to join the DAR.

She submitted an updated membership application to the group at the end of August.

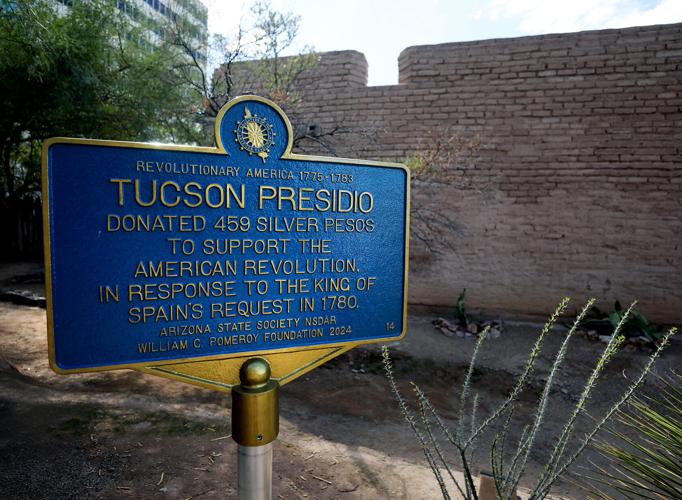

Smith traces her roots in Arizona to long before there was an Arizona — seven generations stretching back to 1761, when her great-great-great-great-grandfather, Juan Manuel Ortega, was born in Tubac.

She said Ortega served as a soldier for New Spain for most of his life, including a stint at the Tucson Presidio during the time when the king was collecting pesos for the American Revolution.

As far as Smith is concerned, her lineage back to Ortega has been thoroughly documented. The only hold-up with the DAR, she said, is that his name does not yet appear on the group’s list of approved Presidio soldiers.

Ziker said a “special DAR Spanish Patriot Taskforce” is now helping to double-check Smith’s genealogy and confirm her ancestor’s backstory.

“It takes a while to prove a new patriot, but the (Presidio’s) service is proven,” she said.

The Sons of the American Revolution has already honored Ortega and accepted his male descendants into its ranks.

In 2018, the group placed its first — and so far only — Revolutionary War gravemarker in Arizona at the Tubac Presidio State Historic Park, near the spot where Ortega was buried in 1817, to recognize him for “aiding in the establishment of the United States of America.”

A man dressed as a Spanish soldier casts his shadow on a historical marker in Tubac for Juan Manuel Ortega, who served at the Tucson Presidio in the late 1700s.

Smith spoke at the dedication ceremony alongside her own two Sons of the American Revolution, Chris and Jeff Herrera, who joined their mother at the event while dressed as Spanish soldiers.

Smith said she is seeking DAR membership as a way to honor her heritage and the little-known contributions of those far from the frontlines of our nation’s independence.

“I’m very proud of being an American. I’m very proud of my Spanish ancestry. I’m very proud of my Mexican ancestry,” Smith said. “I think it’s important for the Tucson Presidio soldiers to be recognized for what they did.”