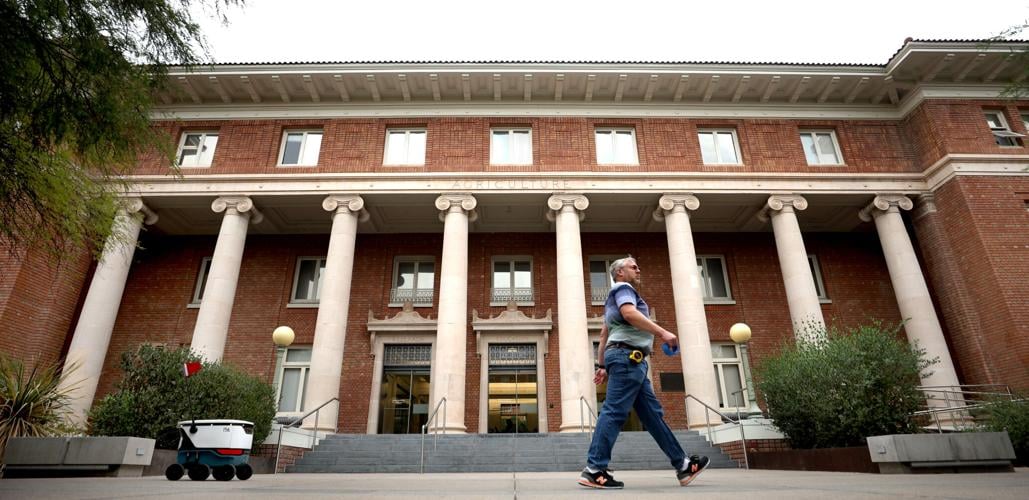

Things at the University of Arizona’s College of Agriculture, Life and Environmental Sciences had been going well over the last few years. Faculty managed to increase research by 12% in two years while simultaneously producing a 7% increase in the number of majors and a 15% increase in the student credit hours that faculty taught.

And yet, earlier this year, the college, also known as CALES, was told by the university that it was in a $20 million deficit.

Most faculty were surprised. According to their calculations, the college would’ve had to hire 200 faculty members to be in that level of deficit. Plus, they say they were told for years by the university’s Chief Financial Officer Lisa Rulney and then-Provost Liesl Folks to spend down their central reserves.

“(We) have a larger enrollment and generated more research dollars than ever before, yet we are suddenly in a budgetary crisis,” Jeffrey Michler, an associate professor in the agricultural and resource economics department, said in disbelief.

Members of the college’s administration who spoke on background claim they informed Rulney that, with continued spending down of their central reserves, the college would find itself where it is today: in a deficit.

They say they warned the university’s senior staff of the imposing deficit, which was predicted using the college’s own internal financial modeling system, in March 2021, May 2022 and most recently on March 20 of this year. University President Robert C. Robbins attended the most recent meeting and was briefed on their concerns, as well, they said.

But Rulney, according to these college officials, ignored repeated warnings and continued to order the college to spend down its central reserves.

“Required overspending and cash stripping by the provost and CFO took our sustainable college and forced it into near collapse,” read one internal document obtained by the Arizona Daily Star.

According to the document, Rulney and Folks “decided CALES was still not spending fast enough, despite the deficit they were shown would happen for three years running.”

The document continues, “They said CALES had too much cash and did not believe us when we said that we would be in deficit. So, at the end of (fiscal year 2023), CALES was taxed (more than) $2 million in gain share.”

Because of the drain on the central reserve, the college must now remove one school and one department each in fiscal years 2024, 2025 and 2026 to avoid dipping below zero in balance. That means that by fiscal year 2026, the college will be just 40% of the size it is today.

It must now grow its revenue by over 7% annually just to break even.

In a statement Friday to the Arizona Daily Star, UA spokeswoman Pam Scott wrote that “there have been no discussions about double digit percentage cuts to any college.”

She added, “As (a) land grant university, the university is committed to supporting our colleges, including the college of agriculture, life and environmental sciences, and its critical outreach through the state.”

Scott did not respond to inquiries on whether Rulney and other members of senior staff pushed CALES to spend down its reserves despite repeated warnings.

UA-wide ‘financial crisis’

The issues within CALES are backdropped by a $240 million miscalculation, led by Rulney’s team, of the overall university’s predicted cash on hand. On Nov. 2, Robbins and Rulney told the Arizona Board of Regents that the UA is in a “financial crisis.“

Administrators originally figured they had 156 days’ worth of cash on hand but are now projecting only 97 for this fiscal year. The UA now significantly lags behind the regents’ requirement of at least 140 days cash on hand, and Robbins has warned “draconian cuts” are coming.

Robbins blamed a financial model he says had been successfully used by UA for a decade but has now been replaced.

“It has become clear that we have overinvested and that some colleges and units have overspent,” he told faculty in a Nov. 11 email. “The model produced a significant overestimate because it did not account for the collective accelerations in spending,” he said. But he defended UA’s overall “significant investments in key areas that advance our strategic plan.”

Robbins has until Dec. 15 to tell the regents how UA will deal with the miscalculation and shortfall.

In a Nov. 22 email to faculty, Robbins wrote: “No decisions about any budget cuts” had been made, although he did commit to not imposing furloughs or cutting retiree benefits. He said, “new budget controls must be implemented to prevent deficit spending in the future.”

Robbins did not mention if layoffs will be necessary. Many at CALES, like Michler, are concerned that the shrinking of programs and departments will cause layoffs.

Robbins, Rulney faulted

What happened at CALES, Michler said, is a further example of the “mismanagement within central administration.”

By forcing the college to spend down its central reserves just like the university did, senior leadership like Rulney and Robbins, he argued, are the ones at fault.

Other UA faculty have also told the Star and the regents the university-wide financial situation is due to mismanagement by the UA president and CFO.

UA President Robert C. Robbins speaking to the Arizona Board of Regents in November.

The issues facing CALES are a “manufactured budget crisis,” according to Katie Zeiders, a professor of human development and family science who serves as a faculty senator representing the college.

“Even at the department level we heard this — that central administration was directing colleges to spend down cash and individual faculty were being asked to spend down research or start up accounts more quickly than they had planned to,” Zeiders said. “The messaging then switched in July 2023, and suddenly colleges were being asked to preserve cash balances with no explanation for this 180-degree change.”

UA CFO Lisa Rulney

To help fix the deficit, university officials have ordered CALES into a hiring freeze. The college has had to rescind at least one job offer and cancel another search halfway through the process.

“Across CALES, we have worked tirelessly to support our mission as a land grant university —through the pandemic we increased our teaching and our research to record levels,” Zeiders said. “And then we are told we cannot hire another needed colleague ... and it comes to light that this is because of senior administrators who have made poor decisions about our university’s finances.”

Rescinding job offers often impacts a college or department’s professional reputation. But more importantly, said Michler, the agricultural and resource economics professor, it creates academic gaps in programs.

When a colleague of Michler’s who studies water issues in Arizona announced their retirement, he and other faculty members within his department began a new search, eventually hiring a candidate they were excited about. But when the university enacted the hiring freeze, the department had to rescind the offer.

“This is coming at a time when water issues are continually on the front page and debated in the Legislature,” Michler said. “This loss comes at a time when we need more than ever expertise in this area. And because of mismanagement by senior administration, the university and our state no longer have this expertise.”

Outside faculty said in an external review of Michler’s department, published this fall, that not hiring for the water issue position “would be a failure in university leadership.”

The departmental review, obtained by the Arizona Daily Star, continues: “Not making those hires really cripples (the department’s) ability to move forward and creates a morale crisis.”

The report, which was sent to senior leadership, including UA’s current Interim Provost Ronald Marx, stated that “the department should be granted the exception from the hiring freeze that was requested twice by the department head.”

That request has yet to be granted.

Cut ‘their own salaries’

Michler remains frustrated with the “incredibly opaque” UA leadership team. If it wasn’t for the forced spending down of the reserves, his college may have been able to continue hiring faculty and remained in a healthy position, he said.

“The fact that our college has spent down a lot of our reserves means there’s no funds left to bridge the gap and so they’re having to (take) drastic measures,” he said. “Senior administration continues to be making these public statements that the budgetary problems are due to mismanagement in colleges. That is not true.”

Administrators in the college warning of an impending deficit were “not being taken seriously,” according to Leila Hudson, the chair of the faculty at the university.

Hudson wasn’t involved in the warnings from the college but was looped into the situation by her colleagues in early November.

“Many of us have had long-standing concerns about the financial management issues dating back to 2020 when the furloughs (imposed during the COVID-19 pandemic) were exacted from us,” she said. “There have been concerns about the sort of financial leadership for a long time.”

Zeiders, who vowed to continue working on this issue in her role as a faculty senator representing the college, echoed Hudson’s statements on administrative financial mismanagement.

“They can start by giving my college the needed money back so that we can continue in our land grant mission,” she said. “If they want to cut anything, it can be their own salaries.”

Get your morning recap of today's local news and read the full stories here: tucne.ws/morning