Frederick Leighton Kramer didn’t purposely set out to launch a century-long tradition when he organized the first Tucson rodeo and parade in 1925.

He was just looking to raise a little traveling money for his polo club.

The wealthy Philadelphia businessman-turned-Tucson-transplant organized the first Fiesta de los Vaqueros rodeo on his sprawling ranch property northeast of Campbell Avenue and Speedway to boost his Arizona Polo Association and the sport as a whole.

“He wanted to send his polo team back East to play against teams there,” said Herb Wagner, unofficial historian for the Tucson Rodeo Parade Committee. “He did have a ranch, but his main thing was polo.”

Though it has since grown into a signature event of its own, the parade started out as little more than a promotion for Kramer’s cowboy competition.

“The parade was a stepchild of the rodeo,” said Wagner, a Tucson native who has served on the rodeo parade committee for 38 years.

The annual midwinter parade will mark its 100th anniversary starting at 9 a.m. Thursday, Feb. 20, when the horse-drawn wagons roll east on Drexel Road from South 12th Avenue and then north on Nogales Highway to the Tucson Rodeo Grounds.

Eleven of Kramer’s direct descendants will serve as grand marshals, including two of his grandchildren, four of his great-grandchildren, three of his great-great-grandchildren and three of his great-great-great-grandchildren. Most of them will ride in Thursday’s parade.

The centennial edition of the rodeo got underway on Saturday and lasts through Feb. 23.

Sunshine city

Only about 30,000 people lived in Tucson in 1925.

That year saw paved streets and city water mains extended to the University of Arizona campus for the first time, according to historian John Warnock’s book “Tucson: A Drama in Time.” Tucson’s first traffic light, at Congress Street and Sixth Avenue, was still two years away.

Several prominent local cowboys and cattlemen helped Kramer recruit competitors and organize his rodeo, including Sid Simpson, Arizona rancher Jack C. Kinney and world champion roper Ed Echols, who would go on to serve as Pima County sheriff.

They were joined in the cause by the group of civic boosters behind a new campaign to promote Tucson as the “Sunshine-Climate City,” a winter destination for both tourists and so-called “health-seekers” battling tuberculosis and other ailments.

Local business owners also jumped on board, sponsoring their own rodeo parade entries and offering contests and specials related to the event. “They were all adamant about having the parade ride in front of their business, so it was quite a serpentine route through downtown,” Wagner said.

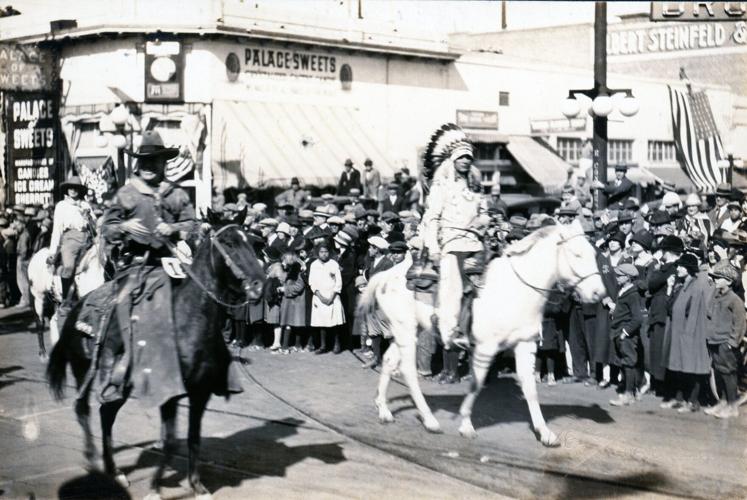

Dressed in a Blackfoot headdress, artist Lone Wolf rides in the first La Fiesta de los Vaqueros Parade through downtown Tucson on Feb. 21, 1925.

The week before the rodeo, Kramer and his fellow polo association board members invited the public to tour the grounds where the event would be held, on the east side of what is now Campbell Avenue, across from present-day Banner-University Medical Center.

According to a report in the Arizona Daily Star on Feb. 15, 1925, the rodeo venue was built “with a view to safety,” including high wire fences to protect spectators and corrals so strong “it would be practically impossible for the wildest horse or steer to break through.”

The three-day competition would offer several thousand dollars of prize money and draw champion cowboys from as far away as Montana and Texas. Plans were made to advertise the show on billboards on places as far away as Kansas City, El Paso and Los Angeles.

The Southern Pacific Railroad offered discounted tickets to Tucson for rodeo weekend, and Wagner said the event drew “trainloads of people” from out of town, many of them from Phoenix, which didn’t have a rodeo of its own.

As hotels filled up, he said, rodeo organizers called on local residents to open their homes to visitors drawn by the inaugural event. The Elks set up dozens of cots in their hall to help with the overflow.

Herb Wagner, Tucson Rodeo parade board secretary, talks about the history of the parade while standing in front of a wagon made by the F. Ronstadt Company Wagon Works, at the Tucson Rodeo Parade Museum, 4823 S. Sixth Ave. The parade will celebrate its 100th anniversary on Feb. 20.

Historic march

On the morning of the parade, under a headline reminding rodeo visitors that “Tucson is dry,” the Star reported the results of a two-week crackdown by federal prohibition authorities that had “practically driven bootleggers out of Tucson and made them afraid to ply their trade, even with tried and true customers.”

According to the newspaper, the targeted, pre-rodeo raids resulted in about 25 captured stills, 50 arrests and the destruction of an estimated 3,000 gallons of liquor.

The parade began at 10:30 a.m. on Feb. 21, 1925, at the El Paso and Southwestern Railroad Depot on Congress Street, just west of where the federal court building now stands.

More than 300 people paraded through the streets of downtown on horseback and on foot, including members of several Arizona Indian tribes and rolling show wagons filled with rodeo clowns and other performers.

Though the event has long billed itself as the longest non-mechanized parade in the country, that wasn’t the case in the early years.

“In 1925, cars were pretty new and a lot of people had them, so they had cars in the parade,” Wagner explained.

Two military bands also took part, one from Fort Huachuca and the other from the garrison in Nogales, he said. The University of Arizona band didn’t march in the parade but did perform at the rodeo.

The 12th Observation Squadron at Fort Bliss in El Paso, Texas, sent eight airplanes to Tucson for rodeo weekend.

Mayor John E. White watched the procession from a reviewing stand at Congress Street and Stone Avenue, alongside the judges of the parade awards and other dignitaries.

Prizes sponsored by local merchants were handed out for such things as the biggest hat, the finest saddle, the oldest man on horseback and the best-decorated automobile.

In the Arizona Daily Star, McLaughlin’s furniture store on South Sixth Avenue advertised its plans to award $10 in merchandise to “the rider of the prettiest horse.” Fleishman Drug Store on East Congress Street offered its “best bottle of Toilet Water” — better known these days as perfume — to “the best looking girl” in the parade.

“One of the prizes was like a 75-pound block of ice,” Wagner said. “That was a big deal back then.”

The Star announced the winners the following day, with parade participant V. L. Cason taking home a ham for having the fattest horse.

Wagner said all of the rodeo competitors were required to ride in the parade. As the cowboys made their way toward the rodeo grounds north of the city, parade spectators simply fell in behind them in their cars to go watch the competition.

The parade was free, but admission to the rodeo cost $1.10 for adults and 50 cents for children.

For an extra 25 cents, spectators could sit in new grandstands that rodeo organizers said were “constructed of the best lumber available” and capable of holding 3,000 people. Or for 50 cents, people could reserve one of the parking spots encircling the field so they could watch the rodeo from the comfort of their own car.

A painting of Leighton Kramer, founder of the Tucson Rodeo Parade, by Lone Wolf. The painting is located at the Tucson Rodeo Parade Museum, 4823 S. Sixth Ave.

The promotional poster for the rodeo featured the “Sunshine-Climate City” slogan, along with an illustration of a cowboy on a bucking bronco by well-known Western painter and part-time Tucson resident Lone Wolf, who rode in the parade in the headdress and full regalia of his Blackfoot Indian tribe. According to the Star, the parade judges awarded him the prize for “Best All-round Indian.”

According to a front-page account in the following day’s Star, the rodeo attracted about 5,000 people on its opening day, “in spite of a quartering northern wind which arose just as the show opened.”

The inaugural event also launched another unique Tucson tradition that turns 100 this year. At the request of event organizers in 1925, local schools closed their doors for the final day of La Fiesta de los Vaqueros. That Monday marked the first-ever rodeo break.

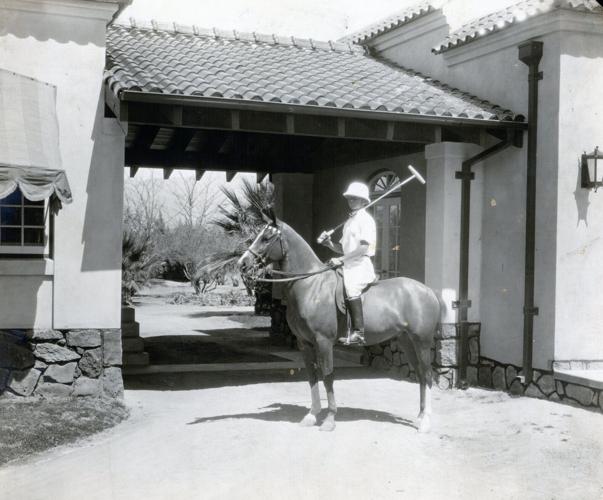

Frederick Leighton Kramer poses in his polo uniform in an undated photo. The Tucson transplant organized the city's first rodeo and parade in 1925 as a fundraiser to send his polo club to a competition in New Jersey.

Horse property

Frederick Leighton Kramer was born on March 19, 1882, in Philadelphia, where he eventually inherited the family’s successful furniture and woodworking businesses.

According to Warnock’s book on Tucson history, Kramer first visited the Old Pueblo in 1918, after cavalry service on the Mexican border during World War I.

He soon began making regular trips here, as he sought relief from his own case of tuberculosis. “He was one of the lungers who moved here for the dry weather,” Wanger said.

By 1924, Kramer had assembled most of the property hemmed in by present-day Campbell Avenue, Tucson Boulevard, Elm Street and Grant Road, and renamed it Rancho Santa Catalina. There, he built a two-story mansion with more than 20 rooms that he shared with his wife and their four children.

The property also featured a 16-stall stable and clubroom, a tennis court, a duck pond, a walled garden, servants quarters, a polo field and eventually the rodeo grounds.

Event organizer Frederick Leighton Kramer wears a black cowboy hat as he rides in the first inaugural Tucson Rodeo Parade in 1925.

Kramer died of tuberculosis in 1930 at the age of 48, and the Fiesta de los Vaqueros moved from his ranch to its current location at South Sixth Street and Irvington Road in 1932.

The parade and rodeo have been held every year since, with a few notable exceptions.

According to the rodeo parade committee’s official history, the procession was canceled in 1944 and 1945 due to gasoline rationing during World War II. The rodeo was also called off in 1945, Wagner said, because the grounds were being used as a temporary camp for trainees from the U.S. Army Air Corps.

The parade moved from downtown to the south-side streets surrounding the rodeo grounds in 1991. Both events were canceled in 2021 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, though the committee did stage a reverse parade of sorts, during which several hundred people in cars drove past displays and performances at the rodeo grounds.

The only fatal accident in the parade’s history occurred in 2007, when 5-year-old Brielle Boisvert was thrown from her horse and struck by a wagon at the corner of Park Avenue and Irvington Road. After months of review, parade organizers decided to carry on with the event the following year, with new safety rules designed to prevent another tragedy.

The Tucson rodeo and parade was never meant to be a one-off affair. Promotional materials and newspaper articles in 1925 regularly referred to the event as the “first annual,” and the resounding success of that year virtually guaranteed its return.

Leighton Kramer certainly had grand plans for it.

In the February 1926 edition of his “Progressive Arizona” tourism magazine, just ahead of the second annual rodeo and parade, Kramer wrote that the Fiesta de los Vaqueros was “a name destined to be as famous in the annals of the ‘Sunshine City’ as the ‘Mardi Gras’ of New Orleans, the ‘Beauty Pageant’ of Atlantic City or the ‘Flower Show’ at Pasadena.”

It hasn’t achieved quite that level of fame over its first 100 years, but give it some time.