Tucsonan Andrew Schot got to know Anne and Margot Frank early in the German occupation of Amsterdam.

With Jewish students no longer able to attend school with their peers, Schot ended up in school with the Frank sisters, whose father Otto Frank had his business in the neighborhood where Schot lived.

Sometimes, the girls joined Schot and others who walked to that neighborhood after school. The would walk to their father's business and go home from there.

Schot was 9 years old in 1940 when the Germans invaded the Netherlands — almost two years younger than Anne Frank and about five years younger than Margot Frank.

We interviewed Schot as part of our #ThisIsTucson Book Club, because for April, we are reading the book "Margot" by local author Jillian Cantor. The novel re-imagines a life in America for Margot Frank had she survived the Holocaust.

When we learned from Tucson's Holocaust History Center that one of the local survivors actually knew the girls, we asked if we could sit down and speak with him.

We met Schot in the Holocaust History Center, 564 S. Stone Ave., where the lights are low, the music is eerie and the faces of dozens of other survivors stare back at you.

Schot, 86 now, recalled his experiences with Margot and Anne Frank, adding that he didn't know them for very long. Beyond the after-school encounters, Schot had met Margot once before when he tagged along on an uncle's visit to Otto Frank's business.

He remembers Otto Frank writing a receipt in German, infuriating his uncle. Margot was called in to rewrite the document into Dutch.

"She was rebellious, Anne was," Schot recalls. "But not Margot. Margot was a sweet lady. You would call Anne a tomboy. She didn't play with dolls and stuff like that. She played soccer in the streets with the boys."

We told Schot the premise of the book club pick — that Margot Frank moved to Philadelphia after World War II. There, she goes by Margie Franklin. No one knows who she is, even as her sister's diary gains fame and a movie adaptation. In the book, she wrestles with her identity as a Jew and her grief over her sister's death. She also wonders what happened to her own diary.

"Margot would never have tried to steal thunder from her sister," Schot says. "She was laid back. Anne was her daddy's favorite, because she was like a boy. Margot had those horn-rimmed glasses. I really don't know how I remember stuff like this."

Schot's own story also has an element of hidden, post-war identity, like the fictional account of Margot Frank's life. He is not a Jew, yet under the Nazi's Nuremberg Laws, anyone who had three Jewish grandparents, practicing or not, was a Jew. Schot qualified. That was enough to destroy his family and ruin his childhood.

After the war, he didn't tell anyone — including his wife and kids — about his own family's World War II tragedy until the mid 90s.

"When we came on board the ship (headed to the U.S.), my mom got us together and she says, 'You know we have an opportunity to start a new life in a new place, so let's not talk about this any more,'" Schot recalls. "'Let's look to the future.'"

So he, his mother and his older sister rarely talked about what happened in the camps.

That is until an Anne Frank exhibit traveled to Tucson in the mid 90s. Schot, a career airman, moved to Tucson in 1967 and retired from the U.S. Air Force in 1976.

He attended an initial briefing about the exhibit, curious to see one of the organizers, a man from his childhood in Amsterdam. Schot ultimately agreed to share his experiences with groups of visiting children.

"The second day I was speaking at the exhibit, I had a group of kids in a room, and I was talking about it, and all of a sudden in the back row I saw my grandson," Schot says. "He didn't know about it and that hit me like a ton of bricks. This was no way for a grandson to find out about his grandpa."

So he gathered the rest of the family for dinner to tell his story.

"Once I opened up to my family, that was the end of it," he says in a 2016 Library of Congress interview. "I wasn't alone any more. They were part of it."

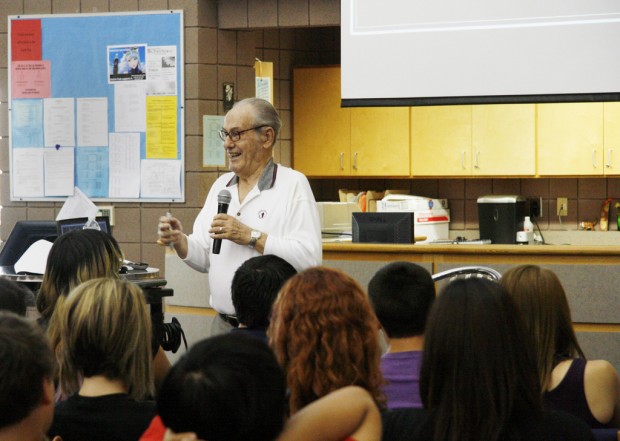

Andrew Schot, 81, speaks to students at Marana High School in 2012. Schot is a Holocaust survivor who speaks to groups about his experience.

Since the revelation, Schot's family — especially his wife — has encouraged him to continue speaking about his personal experiences in the Holocaust.

In addition to traveling the country, Schot has worked with the Jewish Federation of Southern Arizona to speak at venues all over Tucson.

He has also been visiting Amphitheater High School for 21 years to speak to world history students as part of their World War II unit.

"He has a unique way of talking with the students so it's not this gruesome and gory story, which it is, but he has a way of explaining it and even evoking humor so the students pay attention and see him as a human being," says Debra VanSise, a world history and government teacher at the school. "It makes such a difference."

VanSise, who has taught at Amphitheater High for 34 years, sees students riveted by Schot's stories each year, distracted not even by their cell phones. It also helps that Schot usually leads with the Frank sisters and ends with hope.

"It's not all gloom and doom, and there is hope for this generation, and he ends with that," VanSise says.

So he no longer keeps his story to himself.

"I'd just as soon not talk about it, but my wife thinks I should," he says. "Since I came to this country, the positive things in my life, to me, far outweigh the five years of misery," Schot says.

He has three sons, five grandchildren and nine great-grandchildren. He retired after a career in the Air Force and served in the Korean War after being drafted into the U.S. Army not long after immigrating to the United States.

Still, he doesn't forget.

He remembers his older brother being caught up in a roundup of Jewish men, supposedly to work the German factories. His brother went to Auschwitz.

He remembers watching German soldiers march his dad away from the family's Amsterdam home — a moment that illustrated for an 11-year-old boy that "somebody was doing some terrible things." That was the last time he ever saw his father, who ended up in Bergen-Belsen.

He remembers bringing home from school two stars to be worn on the outer pieces of his clothing and the instructions that said "failure to do so was punishable by death."

This Star of David, once stitched to Andrew Schot's exterior clothing, identified him as a Jew during World War II. He has saved it for all of these years in plastic and recently donated it to Tucson's Holocaust History Center.

He remembers hiding in Dutch dairy country with his older sister for two years, eating raw eggs and staying on the run. She was 17. He was 11.

He remembers when they were caught, when Nazis loaded them onto separate trains, when he found himself 13 years old and without his sister in the dark barracks of the Papenburg labor camp. She went to Dachau.

He remembers that year there, eating soup that was basically water with mud in it and sometimes turnips.

He remembers when unknown soldiers marched into the camp to liberate it, about a year after he arrived. Of the 65 people he originally met in his barracks, only five from that group were still alive.

He remembers being given tea and realizing that the British had liberated the camp. "I knew enough to know that there was only one army on earth that took tea into combat," he says during the Library of Congress interview. He weighed 79 pounds.

He remembers meeting a nurse from the Netherlands — finally someone he could speak to — and when she asked him if he wanted to go home.

He remembers when an ambulance pulled up in front of his home with his sister, days after his arrival. She was in "bad shape" but had survived Dachau. She wouldn't speak of what happened to her there.

He remembers when his mother told them everyone who was coming home was home. It was time to move on.

He remembers turning 19 aboard the ship bound for America and the kindness of their new neighbors upon settling in Salt Lake City, Utah in 1950.

He remembers much of it, but he no longer hates.

That's why he tells his story now.

"I don't act angry but I know some (survivors) act angry at the world," he says. "I may be critical of what happened, but there's nothing you can do about it ... It's the old story. If you don't learn from the past, it's going to repeat itself, and it is repeating itself. It's still going on, not necessarily to the Jews, but look at some of the genocide in Africa, and why? If we got along with each other, there is plenty of food on the face of the earth. But we don't want to get along with each other. And if I can talk those kids into changing that, if I can get just one, that's why my wife pushes me."