It's a sign you're living your dream life when some of the stars that fascinated you as a kid growing up in Turkey are now named after you.

Burçin Mutlu-Pakdil, 32, is no longer a starstruck girl. She's a postdoctoral research associate at the University of Arizona's Steward Observatory with a galaxy named after her. Sort of.

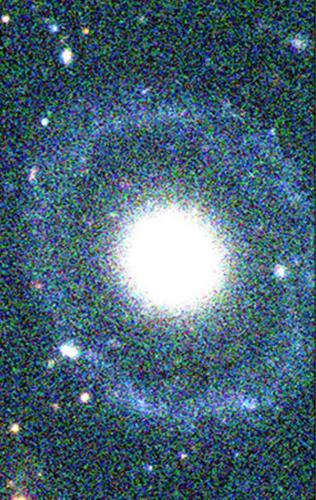

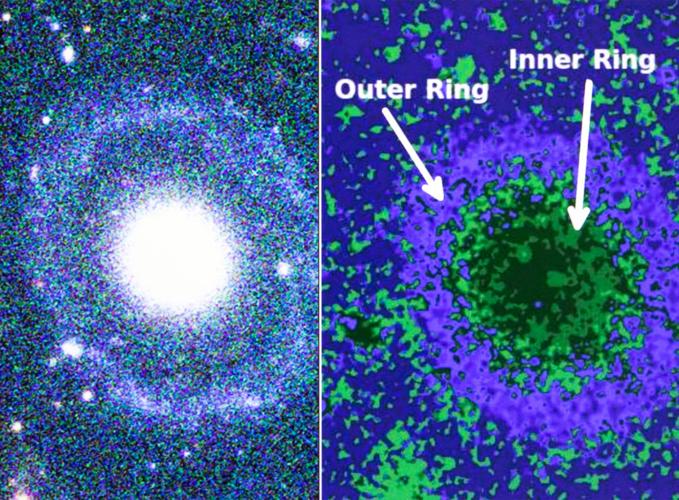

"Burçin's Galaxy," the nickname for PGC 1000714, bears Mutlu-Pakdil's name because she's the one who discovered a second ring surrounding its central body and authored the paper describing this rare galaxy. So far, no other common name has been proposed for the galaxy.

The discovery is a big deal because this is the only galaxy of its kind that scientists know about. Originally, Mutlu-Pakdil and her team thought the galaxy closely resembled Hoag's Object, a peculiar galaxy discovered in the 1950s. That galaxy is unusual and extremely rare because its round central body is surrounded by a circular ring that has no visible material between the ring and central body. Normally, galaxies with rings show several asymmetric features, and the rings have some sort of material connection to the core of the galaxy. Not so with Hoag-type objects, Mutlu-Pakdil says.

The fact that Burçin's Galaxy has two symmetric rings, both unconnected to the core, makes it even more rare, she says.

Burçin Mutlu-Pakdil sits in front of her monitor at Steward Observatory at the University of Arizona in Tucson. These are photos of the galaxy named after her. You can see the two rings that make this galaxy unique in the image on the right.

"This is the first time we are seeing an elliptical central body with two double rings," Mutlu-Pakdil says. "Before this galaxy, we were puzzled with the outer ring. Now we have two rings we need to explain."

Mutlu-Pakdil studied the galaxy as part of her doctoral dissertation at the University of Minnesota. (She received her doctorate in astrophysics in June, following a master's degree from Texas Tech University and a bachelor's degree from Bilkent University in Ankara, Turkey).

Although another team member, Patrick Treuthardt, had noticed this galaxy previously, it was Mutlu-Pakdil who decided to study it and found that unique second ring.

"They didn't have a chance to study it until later and then I came along and said, 'That's so cool. I will study this,'" she says. "And I worked on it and we provided the first description of it as an elliptical galaxy with double rings. ... And then it appears to be this huge thing."

Although she's not the one who nicknamed Burçin's Galaxy, Mutlu-Pakdil says "she's enjoying it."

Mutlu-Pakdil's work studying the structure, formation and evolution of galaxies has earned her a spot in the 2018 TED Fellows program. She'll give her four-minute talk in April in Vancouver.

Mutlu-Pakdil looks forward to the visibility the fellowship will give her. As a girl in Turkey, she dreamed of representing Muslim women in science. Despite her own interest in physics, she never saw any scientists who looked like her.

That's why she invests in girls and young women through science fairs and professional organizations such as Tucson Women in Astronomy and the American Astronomical Society's Astronomy Ambassadors program.

Rachel Smullen, a University of Arizona graduate student in astronomy and astrophysics, co-chairs the university's Tucson Women in Astronomy with Mutlu-Pakdil.

Beyond creating networking opportunities between visitors to the department, graduate students and postdoctoral researchers, the group also works to "support undergraduates in pursuit of grad school if that's what they want to do," Smullen says. "Burçin has had a lot of great ideas about what we can do to encourage women and other minorities in expanding the field."

Through her research at the UA, Mutlu-Pakdil is working with a team to find the nearest neighbor to the Milky Way. She has been in Tucson since August and recently traveled to Chile and Hawaii to use telescopes there. In Hawaii, she had to don an oxygen mask to use the telescope about 14,000 feet above sea level.

Burçin Mutlu-Pakdil with the Subaru Telescope on the summit of Mauna Kea in Hawaii. It's an 8.2-meter optical-infrared telescope.

She is literally reaching for the stars.

Here is part of our amazing conversation with her.

Editor's note: Parts of this interview were edited for clarity.

On becoming a scientist:

"I feel like as long as I have known myself, science, for me, was always comforting. It's solid. You discuss about it. You have proof. ... I would say since I was a kid, I was very amazed with the stars outside. ... When I was in secondary school, there was a project: Who do you want to be? ... I asked my sister, 'Who is the cleverest person in the world?' And she told me, 'I don't know. Einstein?'

"So after that, I started to search about him and the more I looked at Einstein's life, the more I thought science and physics is so cool. I want to do the same thing. At the time, my friends were collecting pictures of artists and journaling about them. And I was collecting pictures about Einstein and galaxies."

On becoming an example to other girls:

"It was always puzzling to me that all these books were about men, especially the physics books, and it's hard to find a woman featured. It's not because women didn't do much. It's because they don't share the story. So I was always like, 'I will be the one.'

"In Turkey, and maybe everywhere in the world, there is this notion that girls just don't do science. It's not because girls don't do science or cannot do science. It's that people don't like them to do science. I'm actually really privileged in the sense that my family always supported me in my dreams. My father couldn't get an education and dropped out of elementary school because he needed to support his family, and he was really into education, so because he couldn't live his dream, he was always very supportive of us to live our dream. In our small circle of family, my sister and I are the first people who left to get education."

On going to college to study physics:

"In my first day at college, a faculty person from the college told me, 'Are you kidding me? You're a woman coming from Istanbul? I went to college in Ankara ... He was surprised: 'Oh my gosh, you are leaving Istanbul and your family as a woman to get your education in physics?' ... And this is college, you know? You need to support me. You need to encourage me. You need to show me the way. But instead, I entered the class and was the only woman..."

On coming to the U.S.:

Burçin Mutlu-Pakdil watches the solar eclipse.

"You know, when I was little, I basically told (my family) I will be in America and I will be at NASA. I was saying all of those things but my main motivation to leave Turkey was at the time, there was a headscarf ban in Turkey, so you couldn't get your education if you wore a headscarf. Right now, it's different, but at my time, the secular people wanted the government places (including public universities) ... but (about) 98 percent of Turkey is Muslim, so you are basically banning Muslim women from pursuing education. ... I wore a hat to try to cover my head ... When I graduated, I said, 'Okay, I will leave to be just myself. Education is my right. ...

"You cannot be yourself, so you are always hiding from faculty members ... You are trying to be hidden ... and my first goal when I was a girl was to be a visible woman in science, and I was living the opposite of it, and it was really challenging for me.

"Coming here to America was a huge thing. People were telling me , 'Oh did you have any culture shock?' And you know, I loved it. I will take this culture shock as long as I can be who I am."

On supporting women and girls in STEM:

"I want women to support each other. We need to show each other that we can do this and we should help each other out. ... In undergrad, I was volunteering ... going to work with poor families and schools ... and it was so fulfilling to see their sparkling eyes, especially because I know my father quit his education for economic reasons ... Sometimes I volunteer for science fairs. One time, there was a girl who was in fifth grade or something, and she was so excited she was telling me about the Hubble Space Telescope and its optical design. ... She was just telling me about it with this huge excitement. I loved her ... Just keep this up."

On becoming a TED Fellow:

"That TED Talk will be just the beginning. I'm getting emails from all over the world, especially in Muslim countries, girls are contacting me saying ... 'You are the first covered scientist I have seen. This tells us that's okay, Muslim women can do science too. ... (Not having a role model) made me feel the need. I needed to show this. Anyone from any background can do science. Nothing stops me. When I study galaxies and try to create my hypothesis, I don't use my faith. I use scientific tools."