A rock star arrived at Davis Bilingual Elementary Magnet School Friday morning.

And 300 students, about 70 teachers and parents, and even Tucson Mayor Jonathan Rothschild packed into the school’s assembly room to hear what he had to say.

To these kindergarten through fifth-grade students, they don’t get much bigger or important than Juan Felipe Herrera, this country’s poet laureate.

Second-grader Elís Aguirre arrived a little early; she wanted her picture taken with the poet, a hat perched on his head and a canvas book bag slung over his shoulder.

Herrera leaned down for a photo, then Elís’ father, Raul Aguirre, scooped her up in his arms and the three of them had their picture taken together.

“I like the poems he writes,” she says. And the stories. Elís is especially fond of Herrera’s “Featherless/Desplumado,” about a boy in a wheelchair who is given a featherless bird that cannot fly. “I like that little birdie,” explains Elís.

Herrera is here because of the Tucson Festival of Books — he will read from his works and take part in a panel discussion on Saturday, March 11. The University of Arizona Poetry Center, which is sponsoring his visit, arranged for his appearance at the school, where students have been studying poetry for the last three semesters. As part of his visit, a couple of grants were awarded so that every student would receive an age-appropriate book by Herrera.

The boys and girls filed in in single lines and sat on the floor. They were all giggles and chatter until principal Carmen Campuzano stood. The buzz slowly died down, then the school’s mariachi band played a few tunes for the guest of honor.

Herrera, sitting off to the side, whipped out his cellphone and as his head bopped and his feet tapped, he filmed the students performing.

He is in his element here. Herrera, the son of migrant workers, the author of about 30 books, and the country’s first Chicano poet laureate, clearly relished the easy flow of Spanish, the children’s enthusiasm and the chance to tell stories and poems to the rapt audience.

Rothschild, a poet and poetry lover, introduced Herrera, speaking in Spanish and then English.

“There’s a very special visitor here,” he says. “Not me. I’m just the mayor.”

Herrera wasn’t going to hog the spotlight. He rose and quickly called up two students and, riffing off his children’s book “Downtown Boy,” asked them what they liked about downtown.

“Downtown is where there are lots of stores,” says Joaquin Soza, not shy about speaking up. “Stores, stores, stores, stores,” Herrera says using the “S” sound and repetition in a rhythmic voice to create a poem on the spot.

A few minutes later, about eight students are pulled up to the area in front of the stage where Herrera is standing.

He instantly creates a play, assigning parts. One was the teacher at the school, several were students, and there was a mother and a father.

They laughed as they were assigned their parts and recited the lines Herrera fed them. The play was about a little boy whose daily lunch includes tortillas. That made all the other students curious and they are all brought back to the boy’s house to sample the warm tortillas his father made and his mother’s “very, very hot salsa.”

Herrera was expected to read from some of his published works. Instead, he sat on a chair on the stage and pulled out a hotel notepad and read the poem he wrote that morning, “Bioacoustical News from Planet Earth,” which celebrates the sounds of the earth. With his arms waving like a conductor, he led the students through lines from the poem’s refrain: “Let us. Let us. Be together. Be together.”

He ended with a poem that he made up on the spot. “‘You have a beautiful voice.’ ‘Me? Really?’ ‘You? Yes you’. ‘Really?’ ‘You have a beautiful voice.’”

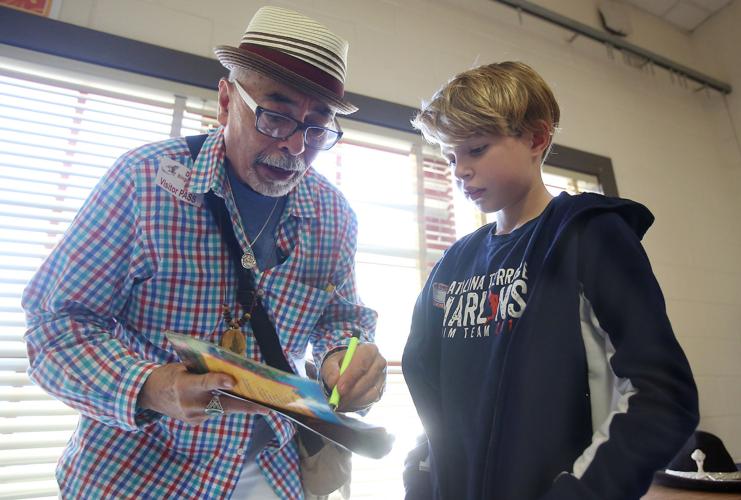

The story in the poem was pulled from his memory as a young student struggling with English, shyness and the migratory life of farmworking families. “Mrs. Sampson taught me the five words, ‘you have a beautiful voice,’” says Herrera after the reading and as children and parents lined up to get his autograph and a picture with him.

“She told me to come to the front of the class and sing. I was shocked. Then she said, ‘You have a beautiful voice.’” The affirmation infused Herrera with a confidence and determination he has never forgotten.

He looks up at the students leaving the room. He sees the same hope that was inspired in him as a schoolboy.

“That’s why I have to give 1,000 percent,” he says about his interaction with the children.

“The future is the present here,” he says. “The future is the present.”