Man’s best friend may have emerged in the Americas about 2,000 years earlier than previously known, according to a study led by an anthropologist from the University of Arizona.

Fittingly, this dogged discovery hinges on a bone found buried in the ground.

A new analysis of a lower-leg bone unearthed in Alaska in 2018 has revealed compelling signs that the canine it once belonged to was being intentionally fed by humans near the end of the last ice age, some 12,000 years ago.

The find, published Wednesday in the journal Science Advances, represents the earliest signs so far of cooperation between the Indigenous people of North America and the ancestors of today’s dogs.

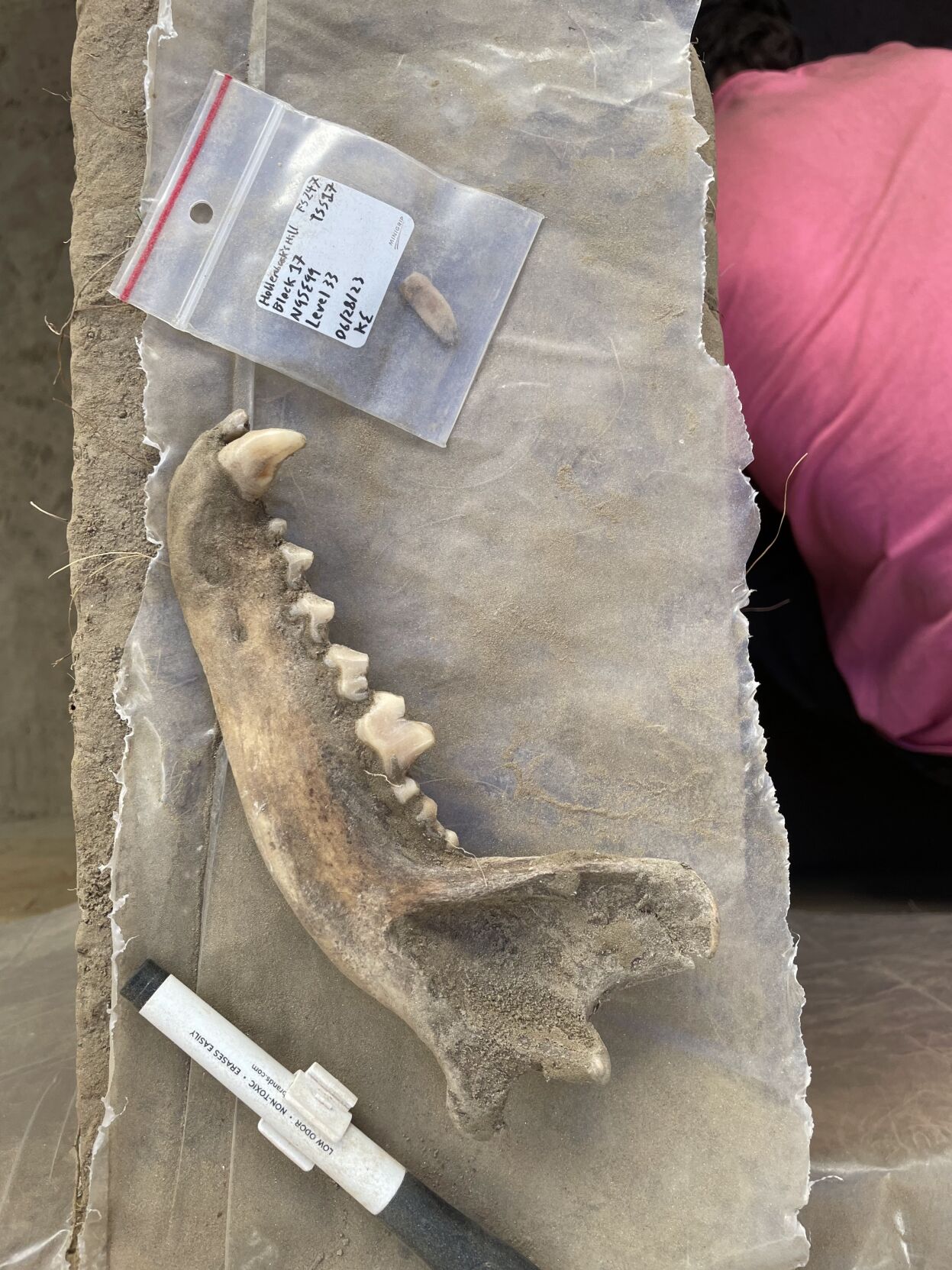

University of Arizona anthropologist François Lanoë examines an 8,100-year-old canine jawbone he just helped unearth during an archaeological dig in Alaska in June 2023. The bone, along with a 12,000-year-old leg bone discovered at a nearby site, are some of the earliest evidence that ancient dogs and wolves formed close relationships with people in the Americas.

“We now have evidence that canids and people had close relationships earlier than we knew they did in the Americas,” said François Lanoë, an assistant research professor with the University of Arizona School of Anthropology and the lead author of the study.

That conclusion was reached after the 5-inch-long piece of canine tibia underwent an isotopic analysis that revealed the clear chemical signature of a marine food source.

A composite scan image shows part of the lower-leg bone of a 12,000-year-old canid unearthed in Alaska. The bone showed traces of salmon proteins in lab testing, leading researchers to conclude that humans had fed the fish to the dogs.

The only protein from the sea available in the Alaskan interior at that time was salmon, but researchers said evidence from other specimens collected in the area shows that the fish was not a significant part of the canine diet.

“This is the smoking gun because they’re not really going after salmon in the wild,” said study co-author Ben Potter, an archaeologist with the University of Alaska, Fairbanks.

At a nearby archaeological site last year, the research team found a canine jawbone dating back about 8,100 years that included some of the same traces of salmon proteins.

Lanoë said both ancient bones contained “a very high signal” for ocean fish, suggesting salmon was a regular part of the animals’ diet. “It’s not something you’d get from stealing a piece of salmon (once) and getting away with it,” he said.

The most likely explanation is that the canines were given the fish on purpose, which points to “a pretty close relationship” between the animals and whoever was feeding them, Lanoë said. “It was obviously beneficial to both of them.”

The canine got food out of the deal. What the humans got in return is unknown, though Lanoë said the later ethnographic record includes accounts of Indigenous people using tamed dogs to hunt, carry packs, pull sleds and provide companionship.

Until now, he said, the oldest proof of a domesticated canine in the Western Hemisphere came from about 10,000 years ago in what is now Illinois.

“People like me who are interested in the peopling of the Americas are very interested in knowing if those first Americans came with dogs,” Lanoë said. “Until you find those animals in archaeological sites, we can speculate about it, but it’s hard to prove one way or another. So, this is a significant contribution.”

Researchers uncovered the two canine bones at separate locations where signs of early human occupation also have been found in the Tanana River Valley, southeast of the city of Fairbanks. The jawbone came from a site known as Hollembaek Hill, and the tibia came from a longstanding dig site called Swan Point, where past excavations have turned up fragments of mammoth tusks carved by ancient human hands.

Researchers say this 8,100-year-old canine jawbone, unearthed in Alaska in June of 2023, represents some of the earliest evidence that the ancestors of today’s dogs formed close relationships with people in the Americas.

Archaeologists have been working in the Tanana Valley since the 1930s and have forged a partnership with tribal communities in the area.

For this study, as with previous investigations, researchers presented their plans in advance to the Healy Lake Village Council, which represents the Indigenous Mendas Cha’ag people. The council authorized the genetic testing of the study’s specimens.

“It is little — but it is profound — to get the proper permission and to respect those who live on that land,” said Evelynn Combs, a Healy Lake member who grew up in the Tanana Valley and now works as an archaeologist herself with the tribe’s cultural preservation office.

She said Healy Lake members have long considered their dogs to be mystic companions, and nearly every current village resident, herself included, keeps at least one as a pet.

“I know that throughout history, these relationships have always been present,” Combs said. “I really love that we can look at the record and see that thousands of years ago, we still had our companions.”

Lanoë has been doing fieldwork in that part of the Alaskan interior for the past decade. He said the area is particularly rich in otherwise rare Paleo-Indian sites associated with the small bands of hunter-gatherers who were the first to inhabit North America roughly 20,000 years ago — or perhaps even longer ago than that.

“There are very few (Paleo-Indian) sites” anywhere in North America, Lanoë said, though one of the most famous ones can be found along the San Pedro River east of Sierra Vista, roughly a 90-minute drive from the U of A campus.

Lanoë came to Tucson for his doctoral work in 2012, after earning his undergraduate and master’s degrees in France. He received a Ph.D. in anthropology in 2017 and joined the U of A faculty full-time after that.

He said there isn’t enough genetic information available to determine if the canine bones he helped uncover in Alaska came from wolves or early dogs. What he and his fellow researchers do know is that the two canines both showed clear signs of being tamed roughly 4,000 years apart, Lanoë said.

“It’s as certain as we can be about something. It’s as exhaustive as archaeology gets,” he said. “We could find something next year that changes our whole thinking. It’s just how science works.”