Rana Schmidt remembers her daughter, Elissa Lindhorst, as having a creative soul with a special place in her heart for animals. Lindhorst loved every type of art — from painting to poetry.

The 28-year-old died on Feb. 24, 2020, just four days after she was booked into Illinois' Madison County Jail on an outstanding warrant for unlawful possession of a controlled substance. Lindhorst’s death was brought on by opioid withdrawal symptoms going ignored and untreated by the jail medical staff, according to court records from a civil suit filed by Schmidt in 2022.

“They just don't treat them like they would if someone was having a heart condition,” said Schmidt. “They just act like they deserve it. They don't view them as people.”

Lindhorst’s story is one example of how substance withdrawal while in custody can sometimes escalate to severe medical emergencies.

Illinois sheriffs and jail staff interviewed for this series said managing opioid and alcohol withdrawal is one of their biggest challenges. Symptoms could include nausea, insomnia, anxiety, increased body temperature, racing heart, muscle and bone pain, sweating, chills and high blood pressure.

In some cases, withdrawal can be fatal for individuals with pre-existing medical conditions.

Elissa Lindhorst

The autopsy of Jerad Traylor, who died while in the custody of the Tazewell County Jail in 2017, showed that he had succumbed to a heart condition related to alcohol and drug use that was exacerbated by dehydration. Prior to that, Traylor had suffered from profuse sweating, extreme chest pains and hallucinations during a four-day withdrawal period.

According to a report released last year by the Prison Policy Institute, approximately 8% of people met the criteria for substance use disorders in 2019 nationally. But substance use disorders are far more common among people who are arrested, at 41%.

The study also states that of the nearly 3,000 local jails nationwide at that time, 63% screened people for opioid disorder when they were admitted and only half provided medications for people experiencing withdrawal.

“An even smaller percentage of jails — 41% — provide behavioral or psychological treatment, and 29% provide education about overdose," the study states.

For offenders experiencing drug, alcohol and mental health problems, Sangamon County Jail Superintendent Larry Beck said the jail is a revolving door.

“A lot of the inmates frequent our jail, and we know who they are. And we already know their medical and mental health history,” Beck said. “We have inmates that come back through our door that are on drugs, alcohol and suffering from mental illnesses.”

Superintendent Larry Beck hosted a tour at the Sangamon County Jail in Springfield in November 2023. He said the staff is trying to keep up with the demand of inmates coming in with severe medical and mental health conditions.

Coles County Sheriff Kent Martin added that opioid and mental health crises work in tandem, creating a snowball effect.

According to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, more than one in four adults living with serious mental health problems also have a substance abuse problem. This occurs more frequently for individuals suffering from depression, anxiety disorders, schizophrenia or personality disorders.

“The individuals that have been using drugs their entire life, it's taken a number on their mental capacity,” Martin said. “A lot of them can’t care for themselves, and they have a lot of health issues stemming from that as well.”

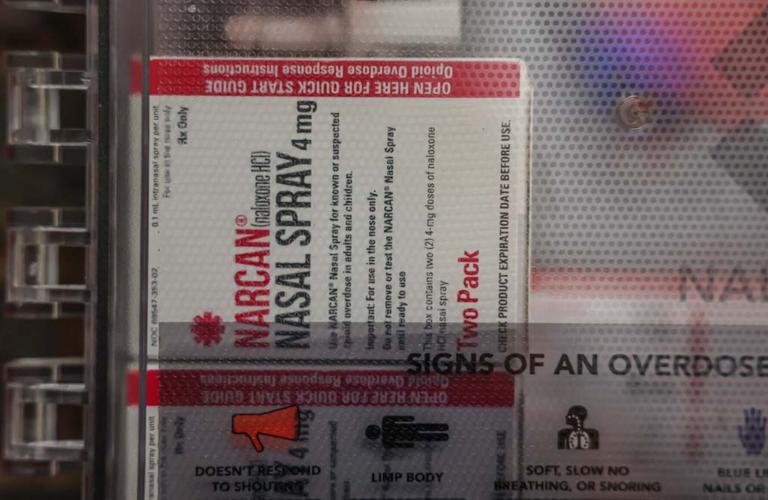

McLean County Jail correctional officers use Narcan kits to treat inmates experiencing opioid overdose symptoms.

The Illinois Criminal Justice Authority conducted a 2018 survey in which they asked the Illinois Sheriffs Association to survey jails across the state with a list of questions regarding opioids and inmates.

About 39% of the state’s jails responded to the survey, which included counties from jurisdictions with relatively high opioid overdose death rates. Those counties represented in the survey accounted for 71% of overdose deaths in 2017 according to the Illinois Department of Public Health.

That same study estimated 63% of sentenced jail inmates meet the criteria for having substance use disorders compared to 9% in the general population.

Identifying substance use disorders

Lindhorst was appearing in court on Feb. 20, 2020, in Granite City, Illinois, when the judge realized she had an outstanding warrant in Hartford. According to the lawsuit, deputies arrested Lindhorst and took her to Madison County Jail where she told the staff she was suffering from opioid withdrawal.

According to deputies on site, a medical form was filled out describing Lindhorst’s symptoms, but such a note was never found in her file. It is unclear if she ever received a medical evaluation.

Medical and behavioral health assessments are required in Illinois when inmates are booked. Although the line of questioning can vary from county to county, many assessments include questions about whether an individual is currently or at risk of detoxing and whether there are complications an individual experiences when they do detox.

Schmidt said jail nurses and other medical staff interviewed at the time claimed they were unaware of Lindhorst’s condition despite her having told them she was suffering from withdrawal.

“They all basically said, ‘We had no idea she was even here; no one ever told us,’” said Schmidt. “They’re claiming the first time they knew something was wrong was that morning, when one of the guards saw the nurse come in for the morning (shift) and said, ‘Hey, I want you to come check on this girl here.’ And they're claiming that was the first information they got that she was even in the facility.”

Lindhorst’s symptoms became more severe over the next three days. Fellow inmates completed a sick slip for Lindhorst, but one of the jail staff members threw it in the garbage where it was later found, according to the lawsuit.

Correctional officers witnessed Lindhorst lying by the toilet in her cell covered in vomit and “made no effort” to seek medical attention, according to the lawsuit. Madison County jail administration declined to comment for this story.

It wasn’t until breakfast that morning that Lindhorst finally received medical attention after inmates began yelling that she had stopped breathing. Lindhorst was then carried from her cell into the main hallway where staff began performing CPR.

She was declared dead at 8:30 a.m.

The Madison County Board in 2023 agreed to pay $3 million to settle Schmidt's case, which also required updated opioid withdrawal training for Madison County Jail staff.

Under the Illinois Administrative Code, at least one staff member of every shift must complete and receive biannual recertification from a recognized course of first aid that includes CPR. Correctional officers also are subject to annual mental health and suicide prevention training. Although staff may receive this training through partnerships with health care contractors or other providers, they are responsible for identifying withdrawal symptoms as a medical risk.

Treatment options

According to the Prison Policy Institute Report, the most effective treatment of substance use disorder — medication-assisted treatment, or MAT — is the least commonly provided. About 24% of jails continue MAT for people already engaged in treatment while only 19% initiate MAT for those who are not, the study states.

Currently, there are three FDA-approved medications used in the treatment of opioid use disorder, including methadone. This helps to “normalize” brain chemistry, block the euphoric effects of opioids and relieve cravings, according to the Illinois Department of Public Health.

MAT, which is also known as medication-assisted recovery, uses a regimen of one of these medications in combination with behavioral therapy, psychosocial support and other services.

More Illinois jails have added the program to their treatment options. According to 2023 and 2024 Illinois Department of Corrections inspection reports, multiple Illinois jails have added MAT programs to their treatment options within the last two years.

Alex Gough, spokesman for Gov. JB Pritzker, said counties have the opportunity to join the Illinois Learning Collaborative to Support Medication-Assisted Recovery for Justice-Involved Populations in County Jails.

This program, which has been in effect since 2021, offers training and technical assistance to its participants to either begin MAT within jails or expand existing programs. Since its inception, 26 counties representing 57% of the state's population outside of Cook County have participated.

However, jails don't always have the resources or participants to keep substance abuse programs going.

Former Woodford County Jail Superintendent Dennis Wertz said the jail had offered an MAT program for a few years with in-house counseling. However, there weren’t enough inmates taking advantage of the program, so the counselors left.

“We do give each inmate a list of medical and mental health providers in our area upon each release if they wish to seek treatment outside of the facility,” Wertz said. “They may also take part in the Gateway MAT program (in Bloomington) even though they no longer have in-house representation at our facility.”

MAT is not the only program that has been endangered by a lack of staffing.

In Macon County, inmates have utilized the Restore program, which was implemented to help people with alcohol or drug addictions, according to Macon County Lt. Jamie Belcher. The 30 hours-per-week program covers life skills, applying for jobs and assistance with reading, writing and arithmetic.

Belcher said the program was on hold after a health care provider was unable to find a qualified person to help run the program. But in July 2024, the jail acquired a full-time facilitator.

The Macon County Jail once hosted a Restore program that would encourage and teach inmates how to acclimate to society once they are out of jail. A lack of staff has made prevented this program from continuing in recent years.

Some jails rely on volunteers to run substance abuse programs, which also presents a challenge.

DeKalb County Jail Administrator Erin McRoberts said that because of the difficulty finding volunteers with experience in successful recovery, she doesn't recall the jail ever offering Narcotics Anonymous or similar programs.

"I live 30 minutes south of (the jail) and if I had to have substance abuse counseling of some sort, I would get it until I got to the DeKalb or Sycamore area, and I've got a significant enough problem and don't have a driver's license, then what?" McRoberts asked. "So to me, that continuation here and the access to that continuation would be very beneficial."

‘We cannot arrest our way out'

Under the Illinois Substance Use Disorder Act, which went into effect in 2019, a judge has the discretion to sentence an individual believed to be suffering from a substance use disorder to probation so long as that individual can be accepted into a designated treatment program.

Rebecca Levin, vice president of policy for Treatment Alternatives for Safer Communities, said the nonprofit has spent the last 50 years ensuring individuals and families affected by substance use and mental health conditions are diverted to resources outside the justice system.

For an individual charged with a crime related to substance abuse, such as illegal drug possession, a judge can impose a sentence that would connect them to a treatment program. Levin said TASC can then offer specialized case management to get people connected to the right resources.

"No matter how well we do in staffing these facilities or no matter what the quality of the clinical care is, it's still not the ideal environment for folks to heal," Levin said. "It's really asking the question of how do we keep folks out of the facilities in the first place.”

On March 21, 2022, Governor Pritzker announced the launch of the Statewide Overdose Action Plan. The state’s collective call to action:

“The opioid crisis affects everyone in some way. Its victims are of all ages, races, and walks of life. The causes of the epidemic are complex, and the state government must work with everyone — health care providers, local agencies, law enforcement, community groups, individual citizens, and national partners — toward a solution.”

As part of the plan, the Illinois Department of Human Services' Division of Substance Use Prevention and Recovery, or SUPR, is partnering with Treatment Alternatives for Safer Communities, Illinois State Police and the Illinois Criminal Justice Information Authority to expand a deflection initiative that would divert individuals with substance use disorder away from the criminal justice system and into community-based treatment, housing and social services.

“We cannot arrest our way out of the overdose crisis,” authors of the plan wrote. “Supporting the needs of this at-risk population is critical to reducing overdose deaths.”

But overall funding in the state's fiscal 2025 budget for SUPR decreased by $45 million.

Jud DeLoss, chief executive officer of the Illinois Association of Behavioral Health, said a great deal of funding came out of SUPR contracts used to provide funding for substance use services outside of Medicaid.

Each year, SUPR enters into contracts using grant funding for behavioral health services to individuals or for services not covered by Medicaid or commercial insurance. If a provider cannot bill Medicaid, they can bill the SUPR contract for services at a rate established by the state.

But by February, DeLoss said SUPR contract funding for the 2025 fiscal year ran dry. The Illinois Opioid Remediation Advisory Board authorized an additional $8 million to close the fiscal 2025 shortfall.

"The proposed (fiscal 2026) funding for SUPR has been increased over the 2025 amounts but we are unsure if that increase will cover the current demand," DeLoss said.

Summer Griffith, public information officer for IDHS, said any overutilization by organizations beyond the amount budgeted per organization may or may not be covered. However, SUPR is committed to reallocating funds for organizations that are underutilized throughout the year.

The state attempted to reallocate funding from existing contracts that weren't fully utilized to contracts that exceeded their spending limit. However, DeLoss said the Illinois Opioid Remediation Advisory Board agreed in April to use $8 million in opioid settlement funds to cover fiscal 2025 shortfalls.

Last year, the state passed legislation increasing the reimbursement rate for residential treatment and detox services 30% over the previous year. However, the state's budget implementation plan for this current fiscal year removed language guaranteeing a 5% automatic rate increase for residential treatment and detox services and a corresponding increase to the amount available for SUPR contracts to ensure services remained at the same level.

The rate reduced to 2% and the contract increase was deleted from revised legislation.

"It was not a good year for SUD services," DeLoss said. "Mental health funding remained at about level."

Gough said the appropriations were adjusted to reflect where program spending is occurring. He added that adjusted appropriations would not impact the progress of the Statewide Overdose Action Plan.

Medical workers, jail staff, lawmakers and loved ones of those who died in jail all agreed that there needs to be other options to assist those suffering with substance addictions.

“Jail just isn’t the place for an addict,” Schmidt said. “They aren’t getting any help. They’re just biding their time.”

Understanding the connections between mental health conditions and substance use disorders

Understanding the connections between mental health conditions and substance use disorders

Updated

The stigma surrounding substance use disorders and mental health conditions has long dominated how both issues are discussed, and how those who experience these issues are seen. Because substance use disorders and mental illness frequently co-occur, meaning individuals experience both at the same time, increased stigma and stereotypical associations of one condition with the other have colored people’s views of both.

Substance use disorders are a type of mental health condition, a disorder affecting the brain that impacts an individual’s ability to moderate their use of substances. Some of the substances commonly associated with this include alcohol, tobacco and nicotine products, opioids like heroin and oxycodone, stimulants such as methamphetamine and cocaine, and tranquilizers, including Xanax and Valium.

Though they manifest in many different ways, mental illnesses are disorders that disrupt the brain, mood, and behavior, and impact daily life. In 2020, 6.7% (or 17 million) of U.S. adults had both a substance use disorder and at least one other diagnosed mental illness. Those with serious mental illness, or mental illness that significantly impacted daily activities, had particularly high rates of co-occurring substance use disorder with certain substances. Misuse of opioids and tranquilizers, for instance, was roughly 6 percentage points higher among those with serious mental illness than those without a diagnosed mental illness.

Understanding why the two conditions often co-occur relates to recognizing that substance use disorder is a mental health condition, influenced by many of the same factors as other mental illnesses like depression and schizophrenia. Genetics, experiences with trauma or violence, environmental conditions, and many other factors impact how and why substance use disorders and other mental health conditions occur. Decreasing the stigma around both conditions will, according to research, likely make receiving treatment easier.

To explore the factors that influence these conditions, Zinnia Health looked at the connection between mental illness and substance use disorder, citing early 2020 data from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (released in October 2021) and academic studies.

21% of US adults suffer from mental health disorders

Updated

More than half of all U.S. adults will receive a mental illness diagnosis in their lifetime, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Many mental health conditions occur together, including depression, anxiety, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, bipolar disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Substance use disorder also commonly co-occurs alongside other mental health conditions. Despite the common co-occurrence of substance use disorder and other mental illnesses, one condition does not always cause the other, and experiencing one condition does not always mean a person will develop the other.

Family history can influence mental health risk factors

Updated

Over the last couple of decades, scientists have increasingly come to recognize the influence of genetics on mental illness. Most research indicates that while there is no one specific gene responsible for mental health conditions, thousands of gene variants can have small impacts on mental health.

Similarly, family history and genetics account for between 40% and 60% of an individual’s susceptibility to substance use disorder. Certain genetic factors can predispose people to dependence on certain substances. Genes can also interact to alter one’s behaviors toward risk-taking or reward-seeking, increasing or decreasing the likelihood of trying substances in the first place.

Research has also shown that similar genes are responsible for the risk of mental illness, as well as for substance use disorder, illuminating new ways of understanding the high rates of both issues occurring simultaneously.

Stress and trauma can be contributing factors for developing mental health disorders

Updated

Traumatic experiences, as well as acute stress, have been shown to have the capacity to alter the brain, particularly the amygdala, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex (which deal with emotion, memory, and decision-making, respectively). But environmental factors like trauma and stress also have the potential to change genetic expression, bringing out some genetic material that may have previously been dormant. The idea that environmental circumstances can trigger changes in our bodily systems, called epigenetics, also means that mental illness or substance use disorder can sometimes be brought on by traumatic or stressful situations.

Apart from the biological changes stress and trauma can inflict on the body and brain, experiencing traumatic events can cause some to self-medicate in order to deal with psychological distress. Using psychoactive substances to self-medicate can create the risk of developing future mental health conditions, as well as a substance use disorder.

Substance use can increase risk for developing other mental health conditions

Updated

Substance use can change the brain in many of the same areas altered by mental health conditions such as anxiety, depression, impulse-control disorders, and schizophrenia. Psychoactive substances can also bring on symptoms similar to those caused by mental illness, including psychosis, paranoia, hallucinations, altered sleep patterns, mood swings, and increased risk-taking behavior. And if substance use begins before the onset of mental illness, it can increase the risk of developing a mental health condition in predisposed individuals.

Targeted behavioral therapies can also help patients with co-occuring mental health conditions

Updated

Behavioral therapies, along with medication-based treatments, can help those coping with substance use disorder and or a mental health condition. Integrated treatments, which involve treating both the substance use disorder and the mental illness simultaneously, are seen as the most effective since they acknowledge the often-intermingled causes and symptoms of the co-occurring conditions.

There are, however, many barriers that keep over half of those experiencing a mental health condition from receiving treatment. Stigma around both mental illness and substance use disorder can make seeking help feel shameful and can inspire fear and real-world consequences for wanting treatment.

Many individuals suffering from a mental health condition or a substance use disorder fear losing a job or being ostracized from their community or family. Another major barrier to receiving treatment is its often-prohibitive financial cost. Stark disparities have emerged in who has access to quality treatment, falling along class and racial lines. While 37.6% of white adults with a diagnosis-based need for mental health or substance use disorder treatment received care, only 22.4% of Latinos and 25% of Black Americans did.

This story originally appeared on Zinnia Health and was produced and distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.