Caged in a cell, Jerad Traylor struggled to breathe and cried out for help, pleading that he felt like he was dying.

And it turned out his feelings of despair were exactly right. Four days after his pleas for help started, Traylor died, alone, in Central Illinois' Tazewell County Jail. He was 31.

Lisa Parrish holds a photo of her son, Jerad Traylor, who died at age 31 while being held in the Tazewell County Jail. At the time of his death on Aug. 16, 2017, Traylor had asked for medical help and told jail staff that he was having trouble breathing.

Fellow inmates said after Traylor died on Aug. 26, 2017 that they heard him begging for assistance as he gasped for air, according to documents in a federal lawsuit filed by his mother. Sweating profusely, hallucinating and suffering chest pains, he can be seen on jail surveillance video, which was reviewed by Lee Enterprises reporters, repeatedly pressing a call button for help that never arrived.

Traylor paid the price of public indecency charges with a far greater sentence than the law would prescribe. An autopsy showed he died from dysrhythmia, a heart condition medical experts said was related to alcohol and drug use but exacerbated by dehydration in the jail.

“If just one person would have listened, maybe things could be different,” said Traylor’s mother, Lisa Parrish. “But instead they chose to turn their heads the other way.”

Photo of Jerad Traylor, who died in the custody of the Tazewell County Jail in 2017 of dysrhythmia, a heart condition medical experts said was related to alcohol and drug use but exacerbated by dehydration in the jail.

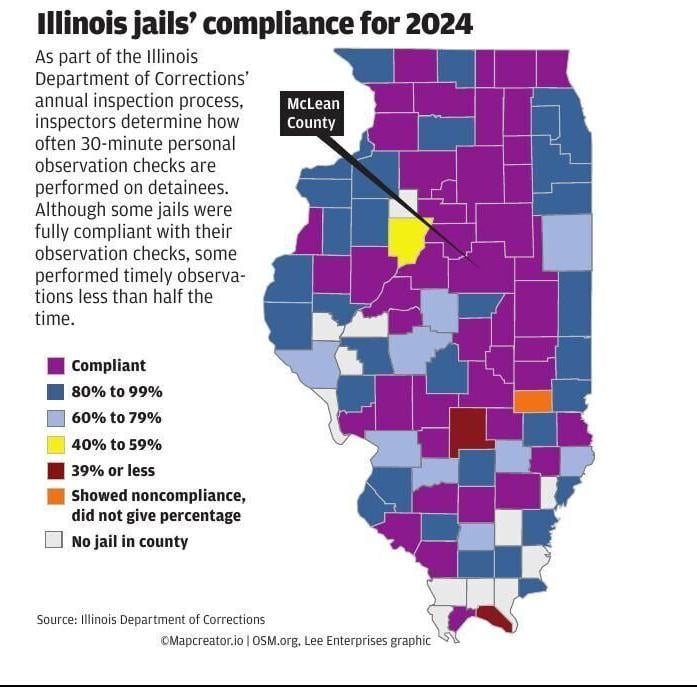

Traylor’s case reflects a systemic problem. The Lee Enterprises Public Service Journalism Team and The Pantagraph spent over a year reviewing nearly a hundred Illinois cases like his, revealing a pattern of inconsistent care and gaps in oversight at county jails throughout the state. As part of the investigation, reporters spoke to dozens of family members, advocates, lawmakers and local law enforcement officials, reviewed inspection records and medical contracts for all of the state's 91 county jails and toured several facilities throughout the state.

Unlike prisons, which house individuals convicted of offenses with sentences greater than one year, jails are short-term facilities meant to temporarily detain subjects pretrial or who are convicted of minor offenses.

While many lawsuits filed by inmates for improper treatment are ultimately dismissed, the complaints offer a window into a fractured system in which complex medical needs often far exceed local resources to address them. As a result, some endure suffering, life-altering injury or death before their case has even gone to trial.

Of the roughly 100 cases filed within the last 15 years Lee Enterprises journalists reviewed, at least 13 people died while in custody including:

- Michael Carter, Macon County Jail, 2015

- Jerad Traylor, Tazewell County Jail, 2017

- Tiffany Rusher, Sangamon County Jail, 2017

- David Brown, Woodford County Jail, 2017

- Marcus Mays, Will County Jail, 2018

- Dalynn Kee, Macon County Jail, 2019

- Elissa Lindhorst, Madison County Jail, 2020

- Blake Lee, Woodford County Jail, 2021

- Eric Petersen, Rock Island Jail, 2022

- Khayla Evans, Lake County Jail, 2022

- Reneyda Aguilar-Hurtado, DuPage County Jail, 2023

- Michael O'Connor, Cook County Jail, 2023

The problem of preventable deaths of pretrial detainees has grown over time. Nationwide, about 1,200 people died in local jails in 2019, a roughly 33% increase from 2000, according to data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics. Of those who died in 2019, about 77% had not been convicted of a crime and almost 40% of them died a week or less into their detainment.

Having handled hundreds of wrongful death cases tied to jails and prisons, attorney Louis Meyer points to a common theme: a breakdown in communication.

Among the staff and medical providers at many facilities, "there's either people that just don't care or think (detainees) are crying wolf," said Meyer, of Chicago-based Meyer & Kiss.

"A lot of times, you can ignore it, and the problem goes away and nothing happens," he said. "Unfortunately, many times you ignore it, and the problem doesn't go away and gets worse. And then I'm getting a call from a grieving family asking me, 'What happened to my son? What happened to my daughter?'"

‘Money is what it comes down to’

County sheriffs and jail administrators say they are doing the best they can with available resources.

“We have limited capabilities in the corrections setting to provide medical care at some of the levels of individuals that come into us,” said Rock Island County Sheriff Darren Hart.

The Rock Island County Jail is located in Illinois near the Iowa board along the Mississippi River.

Hart

"Even though the jail has access to more mental health services than others, there are still weak spots," Hart said.

"It's not the level of care that these individuals need," he added.

To compensate for a lack of staffing or resources, most counties contract with private health-care providers, which is viewed as a more cost-effective and efficient approach than hiring additional county employees. Other facilities turn to nonprofit organizations for care, while some counties rely on their own health departments to meet the growing demand.

In the Tazewell County Jail, Traylor's life was in the hands of correctional officers and a company called Correct Care Solutions. It merged with another company in 2018 to become Wellpath, which provides health care for hundreds of jails, prisons and other detention facilities across 37 states.

Advanced Correctional Healthcare, another one of the nation’s largest jail health-care providers, contracts with almost half of the jails in Illinois and more than 350 facilities across 21 states.

These companies may administer services, but providing additional staffing can be an uphill battle for them as well. Livingston County recently dropped ACH as their healthcare provider with Sheriff Ryan Bohm citing “unresolved staffing issues.”

Multiple other counties across the country have dropped ACH within the last 18 months after finding more cost-effective alternatives. Peoria County Jail Administrator Carmisha Turner said the county rebid for medical services after its contract with ACH expired and chose to move forward with Wellpath.

The control room at Sangamon County Jail is staffed 24/7, according to Superintendent Larry Beck.

'The ever-changing environment'

While state law outlines some fundamental standards, the quality of care and availability of some services can vary wildly between counties.

Meyer, who focuses heavily on litigation in such cases, said this can be true even when two jails have the same care provider. He recalled one example in which two neighboring counties with similar populations had very different ways of treating inmates going through withdrawal from drugs or alcohol.

"One county had a policy and how to monitor and look for it," Meyer said. "The other one didn't even have a policy, yet it was the same company working for both of them."

The patchwork of providers makes it difficult to enforce and regulate standardized care. And with limited resources and staffing, county jails continue to fill in the gap for roles they are not designed or properly staffed for, such as substance abuse centers, mental health facilities and hospitals.

Macon County Jail in Decatur has a medical room where inmates receive health care for concerns that can be treated at the jail. In the event of an emergency, inmates can be transferred to a local hospital.

Former Macon County Jail Director of Nursing Tomika Rehmann described the environment of working in a jail similar to that of an emergency room.

“We see everything, from an earache to an STD to a pregnant person to a suicidal person,” Rehmann said in an interview last year. “You have to be able to handle the ever-changing environment.”

Tomika Rehman, former health service administrator of the Macon County Jail, discusses health care practices at the jail in Decatur.

She added that this is one of the factors that makes it difficult to find and retain medical workers.

If inmates are not getting the treatment they need, their options are limited. Unless they file an internal complaint with the jail or pursue legal action, most instances of poor care go unreported.

ACH President and CEO Jessica Young wrote in an email that the company offers the best quality of health care. And in some cases, they have saved lives and received recognition for doing so.

Jessica Young of Advanced Correctional Healthcare

For example, last year the company awarded its own staff members with three overdose revival awards and one lifesaving award, for reviving a detainee with no pulse.

However, ACH also has been involved in a number of lawsuits in which they have been accused of improper care.

A 2020 lawsuit alleges the company — as part of its pitch to prospective jails — claims to avoid major costs by having detainees with the worst medical emergencies released on their own recognizance or “sent somewhere else.”

The plaintiff in this 2020 case, Nicholas Banning, had been in custody of the Shelby County Jail for four days before he was released on his own recognizance and transferred to a local hospital after his health deteriorated from opioid dependency and withdrawal symptoms that went unacknowledged and untreated. Banning’s medical expenses after spending two months in the hospital would total about $750,000.

When asked about this, Young said the accusation of cost-saving is absurd.

“ACH's contracts are structured so that there is no financial incentive to deny care. We are not responsible for paying for hospitalizations or pharmaceuticals,” said Young. “In fact, poor care results in more lawsuits, which are costly, so we are not motivated to do a bad job. Rather, we encourage both the health care and security teams.”

Unless otherwise expressed in a third-party contract, off-site services such as hospitalization and ambulance transportation typically are covered by the county.

‘In limbo, suffering’

For years, Illinois municipalities have experienced a decline in the medical and mental health workforce as well as the loss of community resources and institutions to treat their most vulnerable populations.

At one time, the number of beds available to treat jail inmates with severe mental health problems was in the tens of thousands. That number now hovers around 1,000.

Sheriffs and jail superintendents interviewed for this series say their biggest challenges when it comes to health care are handling inmates with extreme mental health concerns and those who are experiencing opioid and alcohol withdrawal. Many of those officials addressed the need for a change to the overall system, which includes changes at the state level.

“I really don't have the ability to fully treat these individuals,” said Sangamon County Jail Superintendent Beck. “And as a result of that, they're sitting here in limbo, suffering.”

Superintendent Larry Beck give a tour at the Sangamon County Jail in Springfield on Nov. 8, 2023.

Roughly one year ago, the Sangamon County Jail was holding 10 inmates deemed unfit to stand trial. In total, these inmates had spent 722 days in custody since their evaluation, according to Beck.

If an inmate’s condition continues to deteriorate, whether they are considered “unfit” or not, they will be taken to a local hospital for evaluation, he added. Many jails keep track of these medical histories for repeat offenders.

In Livingston County, Jail Superintendent Lisa Draper said any questions about an officer's conduct when a subject is arrested is documented and archived in the jail's job management system. If a repeat offender is hospitalized for a mental health condition or is suicidal at the time of the arrest, that will be flagged on the person's file.

Young said in an email that the treatment inmates receive in jail is better than what they would get “on the street.”

“Many incarcerated people cannot access (treatment) in the community, are not aware of their medical history, and/or don’t realize the importance of their current medical condition,” Young wrote. “...In addition, when they come into jail, some are too fearful of catching additional charges to provide the health care team with an honest health history, such as substance use."

She added that legislation geared toward providing immunity to patients in exchange for honest substance use history would be a major step in the right direction.

Parrish, meanwhile, believes her son might still be alive had his life not been in the hands of Correct Care Solutions and Tazewell County Jail.

“He needed medical attention,” she said. “If he was on the street and saying, ‘I need help,’ somebody's going to call 911. He was totally dependent alone to take care of his needs. He was not even allowed out to make a phone call to call me.”

‘They are people too’

Parrish remembers her son as having a caring heart even as a child.

“If you were the kid down at the end of the street that people were making fun of, he was making friends with you,” she said.

As an adult, Traylor never shied away from helping his mother with anything she needed — from moving her into a new house to helping with any car repairs she needed. The two were very close and bonded over a love of music, she said.

Some of their favorite bands to listen to together were ACDC and The Rolling Stones.

“I miss my son dearly,” she said. “I miss seeing his face coming in the door and making me laugh.”

Jerad Traylor takes a photo with one of his children. Traylor died in the custody of the Tazewell County Jail in 2017 of dysrhythmia, a heart condition medical experts said was related to alcohol and drug use but exacerbated by dehydration in the jail.

When Traylor was booked into Tazewell County Jail, he was put into the Special Housing Unit, a cellblock for inmates experiencing a range of situations from mental health issues to opioid and alcohol withdrawal.

As he suffered symptoms of alcohol withdrawal, including chest pains and hallucinations, a Correct Care nurse at the jail found that his blood pressure had risen dramatically, according to court documents.

Between the three times his blood pressure was recorded and his complaining about chest pains, the staff was aware there was a need for medical attention. But at no point was Traylor seen by a doctor or transferred to a hospital, court records allege.

Wellpath's contracts with various counties, including Tazewell, have stipulated that the company is required to identify members of the jail population with medical or mental health conditions, which either could be worsened as a result of being incarcerated or would require extensive care.

The sheriff is then informed of these at-risk detainees and must make every effort to have such an inmate released, transferred or otherwise removed from the correctional setting.

After having spent hours trying to get comfortable in jail, around 9:34 a.m. Aug. 26, 2017, Traylor laid down in his cell with his head on a table and his body on the bed.

When a nurse and two other correctional staff members arrived at his cell around 10:12 a.m., Traylor was cold to the touch, court records state. An hour and a half later, Illinois State Police officers arrived and took photos of the scene.

After his death, Parrish filed a lawsuit on Aug. 24, 2018 against the county and Correct Care Solutions, Inc.

According to court documents, the jail and medical staff blamed Traylor’s death on frequent alcohol and drug use. While those factors were cited as contributing, the autopsy report illustrates that the details surrounding his death are more complex.

Dr. Matthew Fox, the forensic pathologist who conducted Traylor’s autopsy, said the cause of his death was cardiac dysrhythmia, also known as an irregular heartbeat, due to hypertensive cardiovascular disease.

Dr. Brian Stubitsch, an expert witness who reviewed the videos from Traylor’s cell and his medical records, stated in his report that Traylor died of preventable causes. He added that the high temperature of the cell due to a lack of proper ventilation or air conditioning contributed to his symptoms.

Stubitsch's report also said that CCS medical jail staff failed to perform proper medical intake, did not have Traylor transported and evaluated due to his initial complaint, did not perform tests for appropriate vital signs nor take action and address abnormal vital signs such as the elevated blood pressure.

Tazewell County agreed to a settlement in November 2020. The claims against Correct Care Solutions were dismissed in their entirety.

“Everyone needs to realize that they are someone’s life,” said Parrish. “This is someone’s brother, friend, father — not just an inmate. They are people too.”

About this series

For decades, some people booked into Illinois county jails have suffered serious injuries and even death after having underlying medical conditions, mental health problems or substance abuse disorders go untreated.

Marcus Mays, 30, was in Will County Jail for 11 days when he died after a grand mal seizure in 2018. Jerad Traylor, 31, was only in the custody in Tazewell County for four days before he died of a heart condition related to prior drug and alcohol use that was exacerbated by dehydration. Elissa Lindhorst, 28, spent also spent four days in the Madison County Jail before dying of untreated withdrawal symptoms.

A year-long investigation by Lee Enterprises Public Service Journalism Team and The Pantagraph determined that these preventable deaths are not isolated to a particular jail or region.

Between 2000 and 2019, the number of deaths of detainees in the custody of a jail nationwide ranged between 888 and 1,200 annually, according to data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics. However, this number may not reflect the total number of deaths of individuals in custody due to changes to federal reporting requirements over the last decade.

Many of the lawsuits reviewed can be traced back to correctional or medical staff either ignoring or not identifying the severity of a medical or mental health condition and confirming the proper treatment that should be administered.

Ensuring that detainees receive adequate medical and mental health services can be hindered by a lack of standardized health care within jails. These facilities are further handcuffed by a lack of funding and a shortage of qualified staff.

Jerad Traylor sits stands alongside one of his children. Traylor died in the custody of the Tazewell County Jail in 2017 of dysrhythmia, a heart condition medical experts said was related to alcohol and drug use but exacerbated by dehydration in the jail.

Jerad Traylor rides a four-wheeler carrying his three kids. Traylor died in the custody of the Tazewell County Jail in 2017 of dysrhythmia, a heart condition medical experts said was related to alcohol and drug use but exacerbated by dehydration in the jail.

23 photos from inside the Macon County Jail through the years

Cell block

Updated

1927: cell block

200 block East Wood Street

Updated

1938: East side of Macon County Jail. Buildings are being demolished to make way for the new building.

Inspection

Updated

1940: Inspecting the new jail's day room are left to right, State's Attorney Ivan J. Hutchens, C.J. Aschauer, architect; J. W. Carnegie, resident engineer with the Public Works Administration; J. H. Samuels, Chicago, traveling engineer for Public Works Administration and Clifford Bell, county recorder.

Sheriff showing available space

Updated

1971: Sheriff Ray Rex has space available for drunken drivers.

Clean cells

Updated

1978: Prisoners are expected to keep their own cells clean; trusties who use this one do pretty well.

Meeting area

Updated

1985: Meeting area in cell block for visitors, lawyers and prisoners.

Typewriter

Updated

1985: Typewriter has to be used standing up in locker because there is no desk area.

Warden

Updated

1985: Lt. John Wrigley, jail warden

Office

Updated

1985: Jail office area with nurses' station in the rear.

Sheriff

Updated

1985: Sheriff Stephen Fisher.

Lockers

Updated

1985: Lockers are for prisoner's effects and street clothes.

Work area

Updated

1985: Lawyers and clients conference and work area

Check in area

Updated

1984: office check-in area and television monitors

cooks

Updated

1987: Cooks preparing prisoner meals. Patricia Brown is the manager and Alice Crawley is kitchen helper.

Inspection

Updated

1989: Robert W. Davis, left, county Board of Supervisors member of the dependent, neglected and delinquent children's committee and Chief Deputy Sheriff Richard Funk ready the new juvenile center which opened in 1969.

Demolition of jail and sheriff residence

Updated

1938: Macon County jail and sheriff residence which have stood for 70 years, started falling today before workmen of J.L. Simmons Co. cleared the site for the new county building. Beyond the sheriff's residence workmen also may be seen attacking the roof the present courthouse, the southeast corner of which is being removed to make way for the new building.

Macon County sheriff Thrift

Updated

1928: Sheriff Thrift.

Food sampling

Updated

1967: Sheriff Jim Doster, center, samples food prepared by Mr. and Mrs. Cleo Dolan.