Ajo, in western Pima County 125 miles west of Tucson, has one of Arizona’s best-known porphyry copper deposits.

It enticed small mining operations by the San Francisco syndicate known as the American Mining and Trading Co. as early as the mid-19th century, though its silver chlorides on the surface were originally discovered by Spanish explorers seeking a more direct route to the Pacific.

The site’s remoteness and technological limitations made ore transport challenging. High-grade copper ore was transported by teams of oxcarts across several hundred miles of desert to San Diego, where it was loaded on ships destined to sail around Cape Horn to Wales for smelting.

Later ventures involving mining promoters A.J. Shotwell and John R. Boddie also failed to fully exploit the deposit. Both foolishly invested in a contraption known as the McGahan Vacuum Smelter, touted as having the ability to extract copper and valuable byproduct metals without water or fuel. The apparatus was marketed by a swindler, Fred L. McGahan, who absconded with the investors’ money.

In 1911, the Calumet and Arizona Copper Co., whose operation was principally out of Bisbee, took an option on 70 percent of the stock of the New Cornelia Copper Co. Geologist Ira Joralemon, mine manager John Campbell Greenway and metallurgist Louis D. Ricketts successfully built a leaching plant at Ajo with the capacity of processing 5,000 tons of ore a day. This advancement served as a prerequisite for the open-pit mining operations that would follow to fully exploit the New Cornelia ore body, composed of the disseminated copper sulfide minerals chalcopyrite and bornite.

Water to sustain the operations was found several miles north at Childs Siding. A rail line was extended from Ajo to connect with the Southern Pacific Railroad at Gila Bend, improving ore transport.

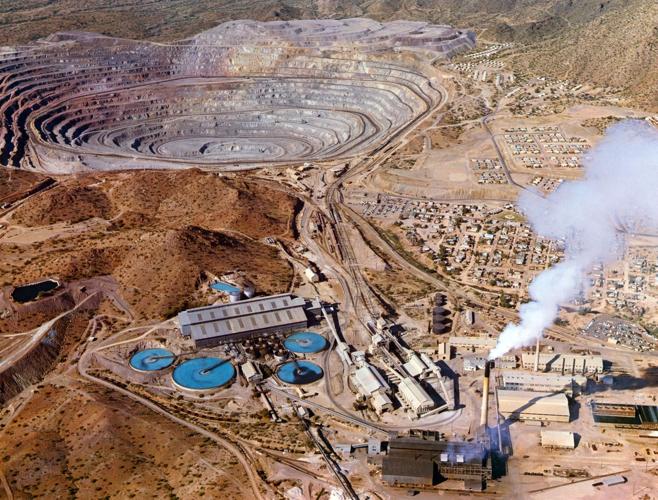

Ajo holds the distinction of being Arizona’s first open pit mining operation, having begun with the first removal of overburden in December 1916, followed by more aggressive earth movement the following year.

At the time, the ore averaged 3.66 percent with 86 cars of it having been shipped to the Douglas smelter. World War I increased the market price of copper to 25 cents a pound, covering the New Cornelia Copper Co.’s operating expenses while enabling it to pay its first dividends to its shareholders in November 1918.

Leaching of the carbonate ore also was initiated and was later processed by electrolysis for the production of pure copper cathodes, lasting until the ore was exhausted in 1930. A concentrator for treating the sulfide ore was completed in 1924, reaching a capacity of 16,000 tons of ore daily by 1936.

During the 1920s, a fleet of 18 steam locomotives served the pit. They operated on a 2 percent grade covering the 2¾-mile distance between the bottom of the pit and the primary gyratory crushers.

Phelps Dodge Co. acquired the Calumet and Arizona Copper Co. in 1931, later expanding the pit with the stripping of part of Arkansas Mountain, the site of the former Cardigan mining camp. Four 22.5-cubic-yard end-dump haul trucks performed this task, avoiding the high cost of track haulage. Electric shovels began to replace the old-time steam shovels with a total of nine in operation by 1939.

Diesel locomotives began operating at Ajo in 1945. The first ones included two units that arrived from Morenci. Steam locomotives reached their zenith in 1947 with 17 rod locomotives operating at the open pit. Soon thereafter they were replaced with a combination of trolley-electric and diesel-electric haulage transport, reducing costs that effectively reduced the cutoff point or minimum grade of the ore selected for processing from that of waste rock.

Prior to the erection of the $8 million Ajo smelter in 1950, concentrates from the open pit were transported to the Douglas smelter. Within three years, the mill was increased to a capacity of 30,000 tons.

Low copper prices and high operational costs in the mid-1980s indefinitely suspended mining activity at Ajo. It is estimated that 445.9 million tons of ore were mined since 1900 with production of over 3 million tons of copper, 463 tons of molybdenum, 1.56 million ounces of gold and 19.7 million ounces of silver.

There remains the opportunity for Ajo to yet again contribute to Arizona’s mining history . The economic potential appears favorable after Freeport-McMoRan’s recent assessment that Ajo contains sulfide ore reserves of 482 million short tons, averaging 0.40 percent copper and 0.010 percent molybdenum, 0.002 ounces of gold and 0.023 ounces of silver per ton.

With the right economic conditions, Ajo may once again become a thriving mining town.