The Giant Magellan Telescope project is a mainstay for the University of Arizona’s top-ranked astronomy programs and its world-renowned mirror lab, helping the next generation of astronomers unlock the secrets of the universe while pumping millions of dollars into the Tucson economy.

But recent developments have cast a shadow on critical federal funding needed to finish the GMT, under construction in northern Chile, as well as for another “extremely large telescope” project, the Thirty Meter Telescope under development in Hawaii.

In February, the National Science Board issued a statement and resolution recommending that the National Science Foundation cap funding for both Extremely Large Telescope projects at $1.6 billion.

What’s more, the board recommended that the NSF choose one of the two projects for continued funding, citing other pressing research funding priorities.

The board recommended that NSF discuss “its plan to select which of the two candidate telescopes the Agency plans to continue to support, including estimated costs and a timeline for the project” at the next NSB meeting on May 1-2.

That’s a problem, since the GMT is expected to cost about $2.54 billion and the Thirty Meter Telescope is expected to cost about $2.7 billion — with as much as half of that funding expected from the NSF.

Top priority

The two telescope projects form the U.S. Extremely Large Telescope program, identified in the most recent National Academy of Sciences decadal survey in 2020 as the top priority for ground-based astronomy.

Both projects have raised a significant portion of their funding from research partners, built much of their telescope hardware and begun ground construction.

GMTO Corp. — the nonprofit corporation that runs the Giant Magellan Telescope project — reports contributions totaling about $850 million from 14 consortium partners, including the UA, Arizona State University, the Carnegie Institution for Science, Harvard University, the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP), the University of Texas at Austin, the University of Chicago and Australian National University.

The UA alone has so far contributed more than $100 million of about $143 million it has committed to raising for the GMT, while expecting about $250 million in contracts for mirror and other work on the project.

Most recently, GMTO announced in February that Taiwan’s Academia Sinica Institute of Astronomy and Astrophysics had signed on as a partner, though funding support was not disclosed.

The Thirty Meter Telescope has reportedly raised about $2 billion in consortia funding from partners, including the California Institute of Technology, the University of California, and scientific institutes in Japan, India and Canada.

In response to the NSB’s recommendation, the GTMO Corp. issued a statement citing the high priority set on the USELT projects by the U.S. Decadal Survey on Astronomy and Astrophysics, also known as Astro2020.

“U.S. astronomy plays a vital role in advancing our understanding of the universe and federal investment is a critical aspect of maintaining the nation’s global leadership and advancing compelling science,” GTMO said.

“We respect the National Science Board’s recommendation to the National Science Foundation and remain committed to working closely with the NSF and the astronomical community to ensure the successful realization of the highest recommendation of the Decadal Survey, which will enable cutting-edge research and discoveries for years to come.”

Telescopes take shape

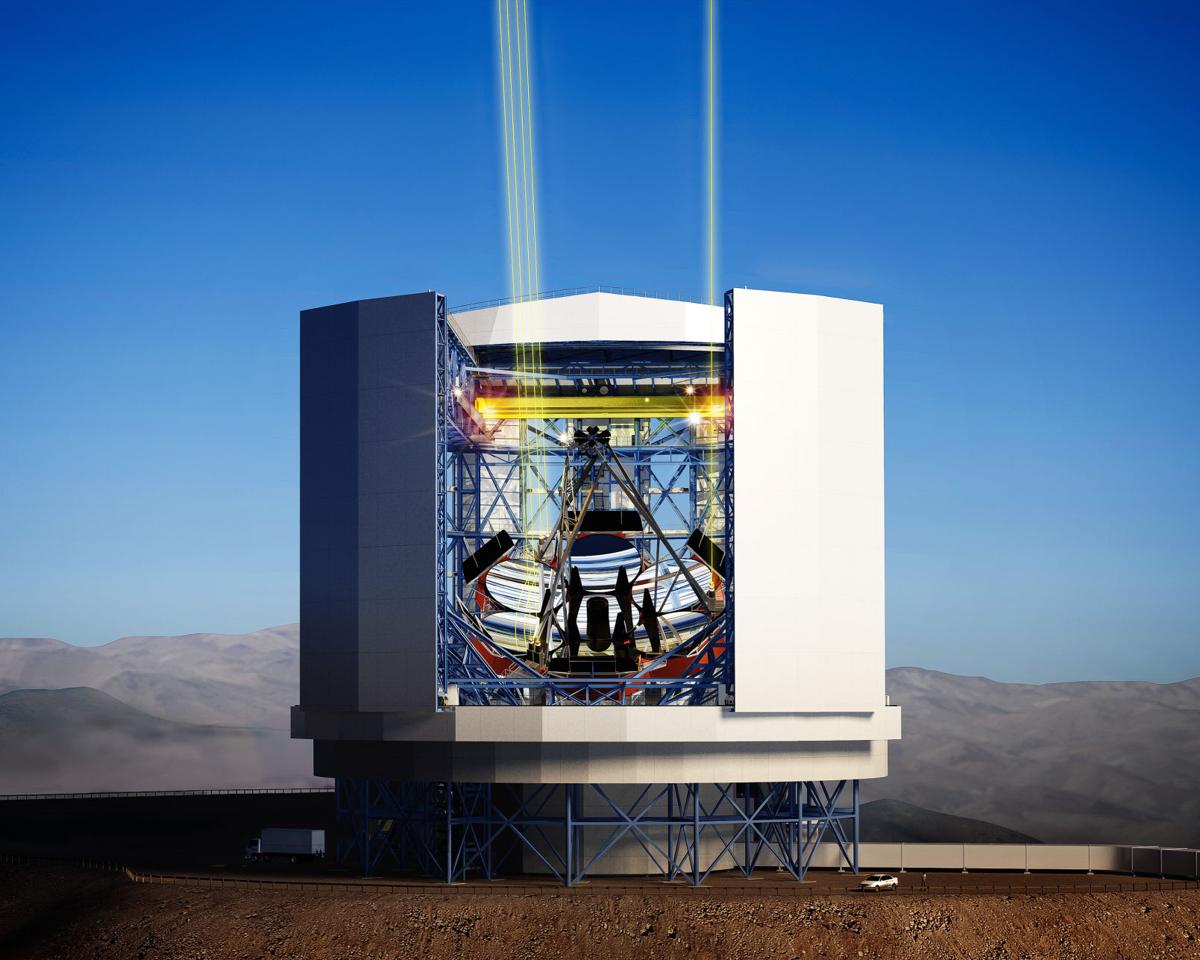

Meanwhile, construction continues apace on the GMT, which was conceived in 2004 and had its first main mirror cast at the UA in 2005.

The seventh and final primary mirror for the GMT was cast last September at the UA Steward Observatory’s Richard F. Caris Mirror Lab, with three completed and four now in the painstaking polishing stage.

“Our site in Chile is ready for pouring concrete and beginning construction of our enclosure, while major technologies and components are being manufactured across the United States,” GTMO spokesman Ryan Kallabis said. “We like to say, our telescope is built in America and reassembled in Chile.”

Construction of the telescope mount structure began in Illinois last year, and the scope’s first adaptive secondary mirror and first precision radial velocity spectrograph — the Large Earth Finder — are set for completion this year, Kallabis said.

The first-of-its-kind Large Earth Finder, which will hunt for habitable planets and signs of life in the visible light spectrum, is slated for testing on the twin Magellans at Carnegie Science’s Las Campanas Observatory in Chile, he added.

The Giant Magellan Telescope will boast a tenfold increase in resolution compared to the Hubble Space Telescope and deliver up to 200 times the power of today’s best telescopes, offering scientists new insights into the evolution and makeup of the universe, according to GTMO Corp.

Meanwhile, the Thirty Meter Mirror, which as its name suggests has a segmented primary mirror about 30 meters or 98 feet across, began initial site construction on Mauna Kea in 2014, but that was halted in 2015 and again in 2019 amid concerns and lawsuits over environmental impacts and protests by native Hawaiian groups who consider the mountain sacred.

The Thirty Meter Mirror was expected to start operations by 2027 but may be further delayed as a new oversight authority was appointed by the Hawaii Legislature in 2022 to oversee development on the summit of Mauna Kea, which already hosts 13 telescopes.

The GMT and Thirty Meter Telescope have presented the two telescopes as complementary, with the GMT providing a eye to the Southern Hemisphere and the Thirty Meter scope covering the Northern Hemisphere.

The two big telescope projects got together with other astronomy groups in 2018 to form the U.S. Extremely Large Telescope Program (USELT) with NOIRLab, (the National Optical-Infrared Astronomy Research Laboratory), an NSF-sponsored research organization formed from a 2019 management merger of national observatories, including Kitt Peak near Tucson.

The GMT is a major program for the UA, whose astronomy and space sciences programs — including the Steward Observatory and the mirror lab, the Lunar and Planetary Lab, the Department of Astronomy and the Department of Planetary Sciences — generate more than $560 million in economic activity annually, according to a report issued by the UA in March.

Funding the future

Though federal funding is never assured, top priorities in the decadal astronomy surveys have been funded by the NSF in the past.

A prime example is the Vera C. Rubin Observatory, which was founded in Tucson as the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope in 2003 and was named a top priority in the 2010 Decadal Survey.

With more than $500 million of its estimated final cost of $680 million supplied by NSF funding, Rubin recently finished construction on a mountaintop in Chile not far from the GMT site and is in final testing ahead of operational use in early 2025.

But in its recent statement, the National Science Board noted that the Astro2020 survey had recommended $1.6 billion in funding for USELT projects, and at that level that the USELT alone would eat up about 80% of the NSF’s historical Major Research Equipment and Facilities Construction budget over five years.

GMTO Corp. President Robert Shelton, a former UA president, has noted that the GMT has raised significant private investment, in contrast to other notable telescopes including the Hubble and Webb space telescopes that have been built solely with government funding.

The push for more funding comes as the NSF should have more resources in the coming years.

The Chips and Science Act of 2022 mandated billions of dollars in spending on semiconductor research and development while authorizing increasing budgets for the NSF.

Part of the law also incorporated provisions of other proposed legislation, such as the 2020 Endless Frontier Act, that authorized new spending to maintain America’s global competitiveness in scientific research.

But Congress still must appropriate that money.

The fiscal 2024 federal appropriations bill that funds the NSF, signed into law in early March, cut the NSF’s budget by 8% to about $9 billion, mainly by reducing spending on grants for research work.

The bill increased the NSF’s research equipment and construction budget that funds telescope projects by 25%, to $234 million for fiscal 2024, though that fell short of the $305 million requested by the science agency.