The Colorado River’s three Lower Basin states including Arizona appear committed to producing a long-term plan by spring to wipe out a longstanding “structural deficit” between river water use and supplies.

Officials or representatives of three water-using agencies, including the Central Arizona Project, said the three states’ water officials agree they all want and need to make permanent water-use reductions that would address the structural deficit. California and Nevada are the basin’s other two states.

The states have generally estimated the deficit at about 1.2 million acre-feet a year, or close to 12 years’ worth of how much Tucson Water customers use annually.

“I think the Lower Basin states are working well together; I think they are going to get to closure on a proposal to handle structural deficit, along with Mexico. Mexico needs to be part of this as well,” said Jeff Kightlinger, a consultant for Southern California’s Imperial Irrigation District, the entire river basin’s biggest water user. “I would estimate we’re 80 to 85% there. There’s still some work to be done; but they are on the right path.”

“It’s no longer six states against one or anything like that,” said Bart Fisher, former general manager and still a board member of the Palo Verde irrigation District, based in Blythe, California. He was referring to a big dispute that flared up early last year for awhile between California and the other six states in the total river basin, including those in the Upper Basin of Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming.

“The Lower Basin is pretty together on their direction,” Fisher said.

Arizona, California and Nevada haven’t yet settled on how the cuts would be split percentagewise among each state. But “I think they are close” on that point, Kightlinger said.

Fisher said California officials have generally agreed to cut about 400,000 to 450,000 acre-feet of use. That leaves most of the remaining cuts to fall on Arizona, since Nevada uses only a small fraction of the Lower Basin’s total water supply. Mexico, which gets about 1.5 million acre-feet a year, will also be expected to be part of the discussions, Fisher said.

All seven river basin states are working on a broader plan to submit to the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, which runs the entire Colorado River reservoir system. By the end of 2026, the bureau and the states need to come up with a new set of rules and guidelines to manage the river. The existing guidelines, approved in 2007, expire by then.

All involved hope the new plan will stabilize the river and its reservoirs, which have been falling rapidly in recent years until 2023’s very wet year.

Supply gap gets worse

The structural deficit is a catch-all term that many water officials and outside experts have used for a decade or longer. It describes a built-in gap between water supply and demand in just the Lower Basin that exists even in what historically have been called normal years.

In a normal year, about 8.25 million acre-feet of water flows downstream from Lake Powell to Lake Mead. From there, it’s released to Lower Basin users, including the Central Arizona Project that provides drinking water to Phoenix and Tucson.

In such years, this chronic gap exists between Lower Basin demand and supply because the three states plus Mexico have typically used as much as 10 million acre-feet or maybe more when evaporation losses are included.

The river’s broader supply-demand deficit has in most recent years been significantly larger, however, at times reaching or possibly exceeding 2 million acre-feet a year. That’s because human-caused warming temperatures have reduced total, annual river flows well below the 20th century average flow of about 15 million acre-feet.

If that trend continues, which many scientists predict will happen, additional cuts will be needed beyond the cuts to the structural deficit. Then, all seven river basin states will need to agree on a more comprehensive water-saving plan.

Starting in 2007, the river basin states have employed two major plans aimed at reducing water deliveries from the Colorado when the river’s water levels get low enough. But neither has succeeded in eliminating even the structural deficit, let alone the broader supply-demand gap.

The potential for a three-state agreement was first reported last week in a blog written by veteran New Mexico water researcher and author John Fleck.

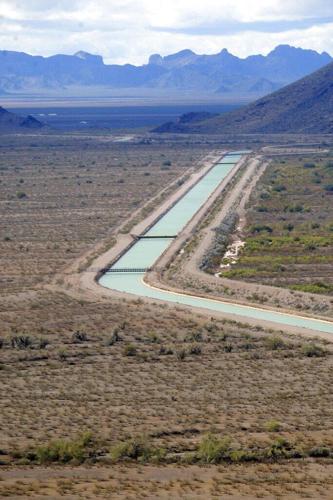

The Colorado River flows in Lees Ferry, Arizona.

An annual conference was held in mid-December in Las Vegas by the Colorado River Water Users Association. “Behind the scenes, a deal is taking shape with the potential to bring Colorado River Basin water use into balance with water supply,” Fleck wrote of it on Dec.20.

No public discussion occurred at the Dec. 13-15 conference about a pending Lower Basin deal. But at one panel discussion, two Lower Basin officials, including Arizona Department of Water Resources Director Tom Buschatzke, said the three states’ officials realize they must tackle the structural deficit to get the ball rolling on broader, seven-state negotiations.

States will “own” the problem

Those officials, including Buschatzke, said their states will “own” the structural deficit.

“There’s a mismatch there,” J.B. Hamby, chair of the Colorado River Board of California, told the Las Vegas conference. “And so, where we’re at in the Lower Basin is a recognition that we have to solve and own that supply/demand imbalance. It’s going to be tough. It’s going to be challenging. But it’s absolutely necessary.”

CAP official Vineetha Kartha and Fisher, of the Palo Verde Irrigation District, confirmed last week to the Arizona Daily Star along with Kightlinger that such discussions are taking place.

“The primary objective is to improve sustainability of the system,” said Kartha, CAP’s Colorado River program manager.

In recent years, various other water-saving plans have caused the CAP to reduce its total annual water use from 512,000 to 592,000 acre-feet a year after years of no mandatory cuts.

“”We don’t want a system that keeps going from zero to 512 or 592 and up,” Kartha said. “We want to eliminate the structural deficit by sharing reductions among the Lower Basin states and Mexico. We’re trying to share the risks and benefits among the Lower Basin — ideally, the entire river basin.”

Kartha said she’s not at liberty to specify how much of a reduction the Lower Basin states are discussing, since “that’s under negotiation.”

One idea Arizona officials have been discussing would overhaul the method by which the states and the Bureau of Reclamation determine how much water deliveries need to be cut back in a given year due to lack of available water.

Typically, those decisions are based mainly on how high water levels are in Lake Powell and Lake Mead. The new approach under discussion would base the amount of shortages and cutbacks on how much water is also available in five other major reservoirs, including Lakes Havasu and Mohave on the Lower Colorado River and three others in the Upper Basin states.

“This approach helps provide a clearer picture of the health of the system, as well as achieve a supply/demand balance by triggering reductions based on the health of the system,” the Arizona Department of Water Resources has said.

The Colorado River flows in Lees Ferry, Arizona.

“To provide as much certainty as possible to water users, and with the understanding that drier futures are likely, the intent is to keep the reservoir contents in a range that ensures a less variable reduction volume. Of course, the primary goal is to avoid crashing the system with this approach,” ADWR said.

Upper Basin’s reaction

A bigger unknown in this issue is how the Upper Basin states will react to the Lower Basin states’ willingness to tackle the structural deficit problem. At the Las Vegas conference and in interviews, Lower Basin officials said they believe Upper and Lower Basin states all need to “share the pain” of whatever water-use curbs are needed to protect the river.

Until now, the Upper Basin states have generally resisted any calls from Lower Basin states to cut their use. One reason is that they typically use far less water, as a percentage of their legal water rights, than do the Lower Basin states.

Another reason is that the Upper Basin states have been wrestling for many years now with their own river water shortages, officials in those states say.

Colorado farmers already suffer water cutoffs, even if they have water rights that predate the Colorado River compact, because “Mother Nature” gives them no choice, Becky Mitchell, Colorado’s Colorado River commissioner, said at the Las Vegas conference.

Those farmers aren’t getting paid in federal dollars to leave water in the system, as some California and Arizona agencies are. The upcoming negotiations must recognize and account for the hardship they already face, Mitchell said.

“The one person that you cannot negotiate with is Mother Nature. She will win every time. She’s been telling us what to do,” Mitchell said.

In a statement sent to the Star last week, Mitchell added, “There tends to be a continued misunderstanding about everything our Upper Basin water users do already — the shortages they face to their water supplies.

“So, while there’s nothing wrong with this ‘all hands on deck’ approach to tackling water cuts in all states — we in the Upper Basin have been in ‘all hands on deck’ mode for decades now. Upper Basin states continue to take cuts, and so far, Lower Basin states have not made similar efforts to reduce their uses.”

She added that all states need to live within the river’s means, “and that is why Upper Basin states have been making sacrifices for years. Our hope is that the Lower Basin will also take on this responsibility. We need to be partners in this fight.

“With this said, I do want to commend my Lower Basin partners on acknowledging that they have to deal with the structural deficit,” Mitchell said.

The basin states hope to get their plans to the Bureau of Reclamation by March 2024. The bureau would like to start analyzing the plans as it does an environmental review of proposals to overhaul the 2007 river operating guidelines.

Longtime Arizona Daily Star reporter Tony Davis talks about the Colorado River system being "on the edge of collapse" and what it could mean for Arizona.