El Charro Café is celebrating its 100th anniversary this year, but the story nearly ended at Year 50.

It was at that 50th anniversary that Monica Flin, at 90 years old, left the restaurant that she started in a small space downtown in 1922 and had recently moved into in her childhood home on North Court Avenue.

Her great-niece Carlotta Flores walked through the door of the home with the intention of closing the restaurant and tidying up loose ends.

But when she looked around, she saw far too much potential to just throw in the towel.

An early El Charro Café menu.

“I told (husband) Ray, this is where I want to run my business,” she recalled earlier this month.

In the 50 years since, the Flores family turned Monica Flin’s small Mexican restaurant into a dynamic family enterprise that now includes three El Charro locations, a downtown steak and seafood restaurant, a collaboration with James Beard Award-winning baker Don Guerra in midtown, a vegetarian-friendly/partially plant-based restaurant on the northwest side and licensee operations in the Tucson, Phoenix, Baltimore and Kentucky’s Blue Grass airports.

Then there’s The Monica, the Flores’ family’s newest venture in the heart of downtown.

It’s an homage to the woman who started it all.

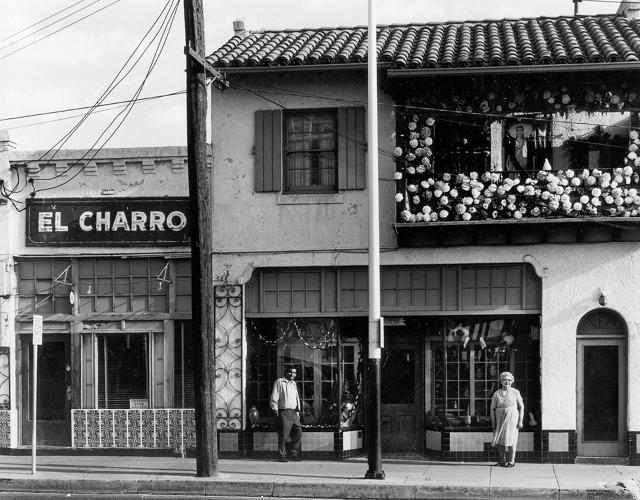

Monica Flin, owner of El Charro Café, 140 W. Broadway Road, is pictured on July 1, 1968, after closing for business. The restaurant was forced to vacate to make way for the Tucson Convention Center and other redevelopment projects.

Buying on credit

Family lore has it that in the beginning, Monica Flin used to go to the Chinese grocer a few doors down from her original restaurant on Church Avenue and East Broadway to buy provisions on credit. She would cook them up in her kitchen and sell to customers before repaying the grocer at the end of the day.

She rented the building and eventually bought it, occasionally decamping to the upstairs apartment on those especially long days in the kitchen.

In the late 1960s, the city paid her a pittance and took her building in the name of downtown urban renewal. She moved El Charro, whose name was inspired by the colorfully dressed Spanish horsemen that she admired, to an area off North Fourth Avenue near the historic Caruso’s Italian restaurant before deciding to move the restaurant around 1969 to the house where she grew up on North Court Avenue.

Flin’s father, Jules, had built the home not long after the family moved to Tucson. Jules Flin was a stonemason of note who was hired by the Roman Catholic Diocese of Tucson to help build the downtown cathedral.

Jules tapped his daughter to make food for his mostly Mexican crew during the construction, which is what got her interested in starting her own restaurant, said Ray Flores Jr., the eldest of Ray and Carlotta's three kids.

After long days in the kitchen at El Charro Cafe on Broadway, Monical Flin, right, would decamp to the upstairs apartment. The building is now part of new HSL apartments, aptly named, "The Flin," at Broadway and Church Avenue.

El Charro had been in the Court Avenue house for a couple of years when Monica Flin decided she couldn’t continue the restaurant. She had left the business to Carlotta Flores and Carlotta’s mother and aunt, who were all living in California. Ray Flores Sr. was running his own electronics company, making circuit boards for power transformers and transistor radios, said his son, and Carlotta was operating a modest catering business.

Carlotta’s mother and aunt moved Flin to a California nursing facility to be closer to family and asked Carlotta to go back home to Tucson and close up the restaurant.

But once she walked through the front door, Carlotta Flores had other ideas.

El Charro Café is housed in the iconic former Flin family home at 311 N. Court Avenue in Tucson.

Five cents in the register

Carlotta and Ray Flores and their two young sons — Ray was 2 and brother Marques was 1 — moved back into the couple’s old home in Tucson in 1972 and set about making repairs to the restaurant.

The city and county had a laundry list of things that needed updating and repaired before they could reopen. So they borrowed money, often using their home as collateral, their son said. While Ray Sr. did the bulk of the construction needed, Carlotta and what was left of her aunt’s crew went to work in the kitchen, using Flin’s well-worn recipes to make food to sell from a stand to workers downtown.

When the Floreses reopened El Charro, “we had five cents in the register,” Carlotta Flores recalled.

Carlotta continued many of Flin’s practices including the sun-dried carne seca, which is still hung in cages on the restaurant’s roof to this day. She tweaked the menu a little, making smaller portion sizes than the mammoth dishes her aunt served and incorporating more healthful ingredients, including oils in an effort to create healthier versions of her aunt’s popular dishes including the famed chimichanga. It’s been said that Flin created the deep-fried burro by accident in the late 1940s or early ‘50s when she dropped one into a pot of hot oil. She screamed “chimichanga” instead of cursing since there were young children nearby and the name and delicacy stuck. Phoenix-based Macayo’s Mexican Food, which has nine Valley locations, also lays claim to the chimichanga with a story similar to Flin’s.

Carlotta Flores smiles while chatting with patrons on the patio of El Charro Café, 311 N. Court Ave., in January 1981.

The Floreses settled into the life of Tucson restaurateurs, juggling parenting and the daily grind of operating El Charro.

“I would open the restaurant and cook and Ray would take the boys to school,” Carlotta Flores recalled. “Then he would come in and work lunch and then he would pick up the boys.”

They welcomed daughter Candace and created a makeshift nursery in a corner of the restaurant so that Carlotta could tend to the baby and the restaurant, which hummed and buzzed along, sometimes coughing a bit in harder economic times. Summers were always a challenge, Ray Jr. recalled. His mom would take out often high-interest loans or max out credit cards just to get through the summers, when University of Arizona students and winter visitors would vanish from Tucson streets.

“They made her put her house on the line constantly just to get through the summer. She never had anyone believe in her so she really risked it all every year,” her son said. “In Tucson back then, summers were really brutal. They would do their business and in the summer lose everything they made. They would AmEx or credit card the summers and she always had a lien on her house. I think until a half dozen, 10 years ago, her home was liened on something tied to the restaurant.”

Carlotta Flores said she and her husband attended their kids school and sporting events, donated food and gift certificates for community causes and became involved in a host of local organizations. She recalled how she would put in a 10- to 12-hour day at the restaurant then change into a business suit to attend a meeting when she was on the boards of several organizations.

It's a family affair for Ray Flores Sr. and Chef Carlotta Flores, seated, of Flores Concepts and Si Charro restaurants, seen here with their children, extended family and grandchildren at El Charro Café in downtown Tucson.

The next generation

As the Flores kids got older, they worked alongside their parents at El Charro.

“I was busing tables in high school and before that, washing dishes in high school, junior high,” Ray Jr. recalled one day in mid-August, sitting in a backroom of The Monica on East Congress Street as the buzz from the lunchtime crowd nearly drowned him out. “Back then, when you had one restaurant and we weren’t doing great volume, we would buy groceries at Associated Grocers.”

The younger Flores also helped out with little odd jobs around the restaurant from minor plumbing or handyman tasks, skills he learned from his father.

He and his siblings went off to college and when Ray Jr. graduated, he took a job with an aunt in New York City for a short while before coming home to try his hand at advertising.

“It was fun for a year, but it wasn’t my family’s business,” Flores said.

He returned to El Charro around the time that Tucson International Airport launched its gateway concept around 1995, inviting local restaurants and shops to open concessions that would introduce travelers to Tucson. The airport venture was the first time the restaurant had a presence outside its flagship downtown location.

Ray Flores Jr., president of Flores Concepts, center, has led the charge to expand the family's restaurants.

The following year, acting at the urging of Tucson fashion icon and longtime family friend Cele Peterson, the Flores family opened its second location of El Charro in the Mercado shopping plaza on Wilmot and Broadway.

“We were at Mercado for years and it helped us to push forward,” Carlotta Flores said, especially with the decline of downtown at the time as the department stores and other businesses fled. “Everything was going east so it only made sense that we, too, had a location out east.”

The expansion was a turning point for the restaurant and Ray Flores Jr.

“That’s when I started realizing this is what I’m going to do,” said Flores, who followed up the Mercado location with ¡Bar Toma!, a tequila bar that he opened in a small office building next door to the downtown El Charro. “Broadway and Wilmot was the turning point for my family. It was a big chapter because it was my chapter, where it started.”

Ricardo Flores, kitchen manager, places strips of beef steak inside the famous carne seca drying cage that hangs over the roof at El Charro Café.

Over the next dozen years, Flores taught himself about lease agreements and smart business practices that included everything from payroll and accounting to supplying the restaurants and making sure the product they served was consistent from location to location. A big push toward that was acquiring a sprawling USDA manufacturing facility on East 18th Street several years ago. From Carlotta’s Kitchen, “30 or 40 nanas” handmake tamales, salsas and other products used in the restaurants and, when possible, sold to small grocers and other restaurants including the airport operations.

They opened El Charro locations in Oro Valley, on East Speedway and on North Oracle Road. In 2009, Flores converted the Speedway location into a car-themed taco and burger restaurant and launched the family’s second concept, Sir Veza’s. He opened a second location at Tucson Mall in 2012 and had outposts in Chandler and the downtown Talking Stick arena, which is now the Footprint Center. The restaurant stayed on Speedway seven years before closing; it was at the mall until 2019, when Flores pulled the plug over a long-standing issue with the building that went unresolved.

Sir Veza’s is still operating in the Tucson and Phoenix airports as well as the Baltimore/Washington International Airport and Kentucky’s Blue Grass Airport.

While Ray Jr. led the charge to expand the family’s restaurants, which were now under the umbrella of Si Charro, younger brother Marcus took charge of the downtown flagship restaurant and sister Candace Flores Carillo took the lead on catering, including at the Stillwell House, which she and Ray Jr. bought about 20 years ago. Flores said the family recently added The Carriage House, Janos Wilder’s former venue at 125 S. Arizona Ave., to their catering venue options.

“Raymon is always looking for the new opportunities and the new places to go to,” said matriarch Carlotta. “I think you always need a pushing force and he is it.”

A large group orders food during a meeting in the basement at El Charro Café in Tucson. The rock in the walls of the home built by Jules Flin are from "A" Mountain.

Full circle

El Charro’s reputation today extends well beyond Tucson’s borders or even the state. The restaurant holds the distinction of being the oldest, continuously operating Mexican restaurant in the country and has been written about in countless travel and food magazines worldwide. Last spring, the popular TV food competition show “Top Chef: Houston” filmed the final two episodes of the show in Tucson and shined a bright light on Carlotta, 76, and the restaurant.

In May, the Flores family turned that light back onto the woman who started it all when they opened The Monica smack in the heart of downtown’s entertainment district at 40 E. Congress St. and in the shadow where it all started one block over on East Broadway and Church Avenue.

In an open kitchen/cafeteria-style setting, The Monica cooks prepare an eclectic fast-casual menu that globe-trots from pizza made with Guerra’s heritage grains dough, deli-style sandwiches and salads, and inventive bowls including the “Tucsonyaki” chicken and rice drizzled with a teriyaki style sauce that adds local spice.

Sasha Flores, center, works the register at The Monica. The newest eatery under the Si Charro umbrella has an eclectic menu, much like that of the menu of the original El Charro, which opened 100 years ago.

Ray Flores Jr. said the Monica is a return to Flin’s diverse menus of the 1930s, when El Charro was one of only a handful of Tucson restaurants and Flin had to appeal to the masses, serving everything from fried eggs and fried chicken to burgers and beef tongue.

“The original charro menus were really eclectic,” he said, ticking off everything from cheese sandwiches to ham and eggs that appeared on the early El Charro menus. “She had this very random menu and her kitchen was always open. She was just kind of all over the place. Monica was striving to be a little bit of everything ... to satisfy the tastes of the day.”

But the restaurant proves a bigger side of Flin’s legacy for Ray Flores.

“These restaurants are way more than the four walls. They are our life. For better or worse, it’s a marriage,” he said. “Restaurants are always in my heart.”

“It’s been a very fulfilling, fun yet demanding life. But at the same time, I would probably do it all over again,” added his mom.

Photos: Historic, family-owned El Charro Café in Tucson

One of the original locations for El Charro Café. which fronted Broadway Road, west of Church Ave, shown ca. 1960s. Founder Monica Flin is at right.

The famous El Charro Café today, at the iconic former Flin family home at 311 N. Court Avenue in Tucson.

Carlotta Flores at age 4, left, with El Charro Café founder Monica Flin in 1950.

Ray Flores and Carlotta Flores with Father Tom Calalane and Father Arsenio Carillo during blessing of the wine and cheese cellar at El Charro Café, Tucson, on Sept. 16, 1973.

Carlotta Flores smiles while chatting with patrons on the open-air patio (front porch) of El Charro Café, 311 N. Court Ave., in January, 1981.

Carlotta Flores in 2006, outside the legacy El Charro Café at the Flin family home in downtown Tucson.

El Charro Café owner Carlotta Flores in 2021.

Ray Flores Sr. and Chef Carlotta Flores, seated, of Flores Concepts and Si Charro restaurants with children and grandchildren at El Charro Café in downtown Tucson.

Raymon Flores Jr., president of Flores Concepts, center, during a meeting at The Monica in Tucson. Flores leads the family venture established by his great aunt Monica Flin and mother, Carlotta Flores.

El Charro Café, 311 N. Court Ave.

DeAnna Ali, Gloria Tovar and Yvonne Abeyta, friends, place their orders with waiter Samuel Bolanos at El Charro Café in Tucson. Abeyta's grandmother, Eugenia Morales, worked at El Charro Café as a waitress.

A large group of employees order their food while having a meeting in the basement at El Charro Café in Tucson, surrounded by rock from "A" Mountain in the walls of the family home built by Jules Flin.

Will Dean, center, and his girlfriend Elise Cade get in a late lunch in the covered porch at the front of El Charro.

El Charro Café conmemorará el 100 aniversario con un plato que incluye, de izquierda a derecha, un taco de carne +del menú original, una enchilada de carne seca y un tamal de elote del menú original.

Juan Chacon, cook, places seasoned chicken on a grill at El Charro Café.

There are many colorful murals, paintings and artworks throughout the El Charro Cafe.

Sen. John McCain, left, with Cindy McCain, at El Charro Café in Tucson for dinner on Nov. 22, 1999. Pima County Supervisor Ann Day and Congressman Jim Kolbe are lower right.

El Charro Café employees in 1940.

Monica Flin, left, and Grace Montano with the Anheuser-Busch Clydesdales on Broadway Road in Tucson, 1945.

Undated photo of Monica Flin (back row, center) with waitresses at El Charro Café in Tucson.

Staff of the El Charro Café, mid-World War II, 1943-44.

El Charro Café owner Monica Flin, center, flanked by waitresses, ca. 1950.

Newspaper ad for El Charro Café in 1939.

An early El Charro Café menu.

An early El Charro Café menu.

An early El Charro Café menu.

An early El Charro Café menu.

La Placita Park, shown in the mid-1960s, on West Broadway Boulevard near South Church Avenue. It was surrounded by several businesses including El Charro Café and the Ronquillo's Bakery.

In this Tucson Citizen graphic illustration from the mid-1960s, the realignment of Broadway Road in Tucson for urban redevelopment can be seen. All the buildings shown in the photo were demolished, except where noted, including: 1) Tucson Army Surplus, 2) Plaza Theatre, 3) Ronquillo's Bakery, 4) La Placita Park (preserved with La Placita Village), 5) Greyhound Bus station 6) El Charro (preserved within La Placita Village), 7) Belmont Hotel, 8) Myerson Building.

Monica Flin, owner of El Charro Café, 140 W. Broadway Road, Tucson, on July 1, 1968, after closing for business. The restaurant was forced to vacate to make way for the Tucson Convention Center and other redevelopment projects.

El Charro Restaurant, 140 W. Broadway Road, Tucson, on July 1, 1968, after closing the business. The restaurant was forced to vacate to make way for the Tucson Convention Center and other redevelopment projects.

El Charro Restaurant, 140 W. Broadway Road, Tucson, on July 1, 1968, after closing the business. The restaurant was forced to vacate to make way for the Tucson Convention Center and other redevelopment projects.

A 1969 Arizona Daily Star story on reopening of El Charro Café after owner Monica Flin was forced to vacate the original building to make way for urban redevelopment. The restaurant reopened in the Flin family home.

The remains of El Charro restaurant, and the stables on the far right, as it appeared on May 27, 1972 in downtown Tucson. Parts of the structure go as far back the 1860s. It became part of the $6 million La Placita Village office complex. Workers poured concrete around the foundation of the old building to stabilize it during construction of the 2.6 acre complex.

Obituary for El Charro founder Monica Flin, who died in 1975 at age 90.

Mercy Tapia, shown in 1974, made tamales at El Charro Café for 51 years.

Piedad Teralta and John Cocoa prepare an enchilada filled with non-fat yogurt and spinach at El Charro Café, in July, 1994.

Ricardo Flores, kitchen manager, places beef inside a drying cage on the roof of El Charro Café .

The old carne seca drying cage, suspended above the interior patio for all to see at El Charro Café.