The ground is stabilizing under Tucson and Phoenix, but sinking faster than ever under many rural farming areas around the state.

The phenomenon known as land subsidence is showing a two-way trend due to differences in the kinds of water supplies and water management used in varying regions, officials say.

Subsidence has been a problem in Arizona for decades. It’s the collapsing of the soil due to chronic pumping that exceeds the rate the aquifer is replenished by rainfall and other sources.

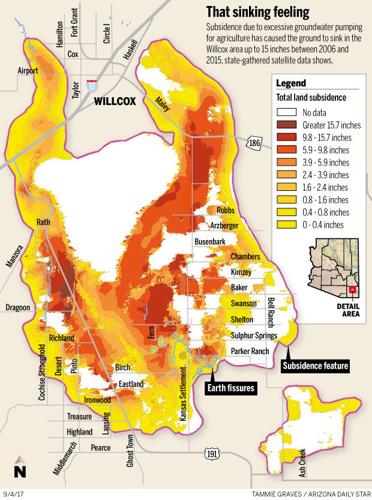

But today, where state regulations on pumping are stricter and renewable supplies are available — like Tucson — it’s getting better. In places like Willcox in Southeast Arizona’s Cochise County, and in parts of La Paz County in Western Arizona, where such regulations and renewable waters are non-existent, it’s getting worse.

This matters to state water officials, environmental activists, researchers and others interested in water because subsidence causes at least two major problems.

It often triggers fissures that can damage roads, pipelines, power lines, bridges and canals, and can swallow cars, old furniture and even animals at times. About 167 miles of fissures have been mapped in Arizona. In parts of Cochise County, new ones open yearly, Arizona Geological Survey officials say.

Subsided lands are also more likely to flood because the sinking can alter natural drainage slopes, state officials say. Such areas have flooded at times in Arizona City in Pinal County, in and around Luke Air Force Base in Phoenix’s West Valley area, and in the town of Wenden near rural farmlands in the McMullen Valley west of Phoenix.

In Texas, land subsidence also has significantly aggravated flood damage over the years in Houston, including during Hurricane Harvey, according to news reports from that area.

“It can and definitely has impacted infrastructure. It’s impacting floodplains. It’s definitely changing the properties of the aquifer and it’s compacting areas that used to store water that won’t be able to store water now,” said Brian Conway, an Arizona Department of Water Resources (ADWR) hydrologist.

At the same time, Arizona is far better off than California’s Central Valley, where agricultural pumping during the peak of the state’s drought in 2015 lowered some areas 1 to 2 feet, he said.

Where it’s getting better or worse

Some statistics:

- Since the early 1990s, the subsidence rate dropped about 90 percent in the Tucson area and 25 percent in the Phoenix area.

Over a year in Tucson, “it’s very hard to detect any ground motion” indicating sinking, said Conway, who supervises the water agency’s geophysics surveying unit. It usually takes two years for the ground to sink enough in Tucson for the movement to be detected, he said.

- In rural Cochise County and other agricultural areas, subsidence rates have jumped two to five times since the early to mid-1990s. In the Willcox area, the rate of ground collapse has tripled since the mid-1990s, ADWR officials say.

In the past year, the ground under Willcox dropped between 5 and 6 inches, or 14 centimeters. That compared to 3.5 centimeters or about an inch and a half in the mid-’90s, said Conway.

In the Willcox Playa, where thousands of sandhill cranes migrate every winter, subsidence rates are unknown because the playa’s water makes it impossible to detect ground movement by satellite technology, Conway said.

Subsidence rates have also skyrocketed in the McMullen Valley west of Wickenburg, where the ground drops about as fast as in Willcox. The Douglas, Fort Grant, Bowie and San Simon areas in Cochise County and the Ranegras Plain east of Quartszite in Western Arizona have also experienced escalating subsidence rates.

Behind the trends

Tucson and Phoenix’s improvements are credited partly to the 1980 Arizona Groundwater Management Act. It required these areas to slowly clamp down on groundwater pumping by conserving water. They were placed in state Active Management Areas that set up periodic water-management plans.

And in Phoenix starting in 1985 and Tucson starting in 2001, the use of Central Arizona Project water brought by canal from the Colorado River has reduced pumping much further.

The Green Valley-Sahuarita area south of Tucson lies within the Tucson water management area. It has not had CAP water, although efforts are underway to bring CAP there by two pipeline projects. One, for the Farmers Investment Co.’s pecan groves, should start construction next spring and deliver CAP water a year later, a FICO spokesman said.

But in the Green Valley area, there’s only been moderate subsidence of a less than an inch to an inch and a half a year. That’s because the groves are fallow part of the year. Typically, the ground sinks when the pumps to the pecans run between February and May and recovers during the winter when pumps are idle, the state agency says.

In rural farming areas such as Willcox, many farmers, ranchers and other landowners didn’t want groundwater regulations in 1980. They were concerned they would violate property rights and hurt them economically.

Concerned about the growing subsidence problem, the state started conducting detailed monitoring of subsidence in 1997. Since 2002, it has used satellites to map subsidence trends. That costs $125,000 a year, paid by state agencies, county flood control districts and local water districts.

What’s next

Now, there is talk of enacting groundwater regulations for the rural areas. As part of a statewide water initiative, the state water agency has established 22 areas around Arizona where it has been conducting public meetings and gathering data to consider future management actions. Gov. Doug Ducey’s office has established a separate work group that’s examining groundwater issues this summer in private meetings.

“They are going to have to up their regulatory framework outside the active management areas,” said Val Little, director of the Water Conservation Alliance of Southern Arizona. “It will be a pitched battle, but it’s time. It has to happen.”

“We don’t want unnecessary regulations, but where regulations work, we ought to use them elsewhere,” added Eric Holler, a retired manager of the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation’s Tucson office, who does volunteer work on local water issues as well as private consulting.

“You want to be able to balance economic development in anticipation of environmental problems,” he said.

The Arizona Farm Bureau still will not favor new regulations when they increase costs for farmers and ranchers.

But it’s particularly concerned about the prospect of what the bureau’s Stephanie Smallhouse calls “one-size-fits-all rules that apply statewide.”

The state needs to take time to design rules specifically for individual regions, said Smallhouse, the bureau’s first vice president.

“One-size-fits-all rules fix a problem in one place, and start another somewhere else,” said Smallhouse, who farms in the San Pedro Valley in Pima and Cochise counties.

“It’s not just rural areas of Arizona versus urban areas. Rural areas are different from one another” and should be treated differently, she said.