In 1988, David Lazaroff got a call — an important one. About jellyfish.

A couple years earlier, Lazaroff had worked for a decade as an environmental education specialist at Sabino Canyon.

“Everyone knew me there and whenever something odd or interesting showed up in Sabino Canyon, I’d get a call,” he says.

That’s what happened in 1988, after a few hikers spotted something strange in Sabino Creek and reported the sighting to folks in the visitor center.

Jellyfish. They saw jellyfish.

Lazaroff had been interested in freshwater biology, studying critters long before graduating from the University of Arizona in 1984 with a degree in ecology and evolutionary biology.

People are also reading…

He didn’t know if he’d ever see freshwater jellyfish in person, but he hoped the day would come. This was that day.

He followed the directions given to the visitor center and made the trek into Sabino Canyon on a warm day in mid-July.

“I walked way, way up and — no jellyfish,” he says. “I was kind of disappointed.”

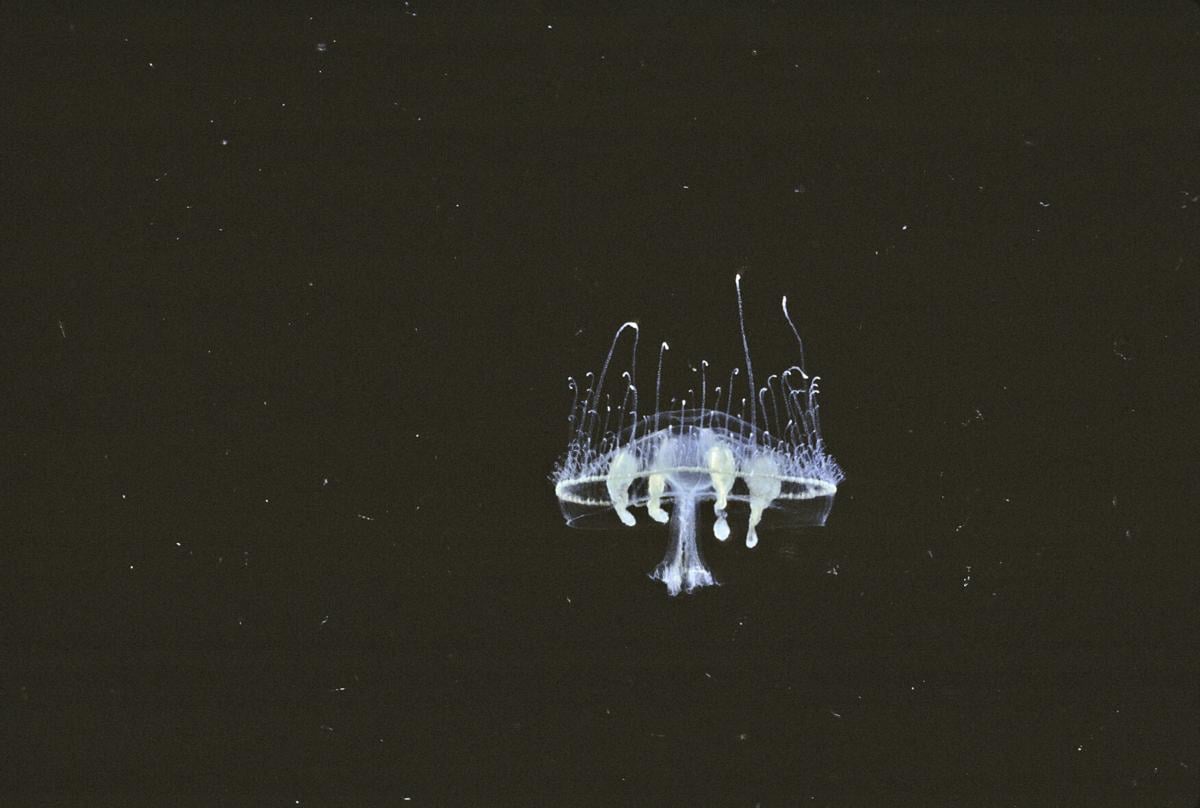

But a week later, someone else reported a sighting — and this time, better directions were left with the visitor center. Lazaroff started his hike and then he saw them — teeny tiny jellyfish, less than an inch across, pulsing in a desert creek.

David Lazaroff found freshwater jellyfish in this pool at Sabino Canyon on July 23, 1988.

The mystery of freshwater jellyfish

The jellyfish may not be rare, but they’re rare to see.

They’re commonly called freshwater jellyfish — their scientific name is Craspedacusta sowerbyi — but technically speaking, they’re not really jellyfish. They look like them, they eat like them, they act like them. But they’re technically part of a different class of organisms, with “very, very minor kind of anatomical differences from true jellyfish,” Lazaroff explains.

When the jellyfish are visible, they’re in low water that’s been still for a while. They’re weak swimmers, so you won’t see them when the water is running.

Most of their lives, though, are spent in a completely different form — one that doesn’t look like jellyfish at all. It’s called a polyp. Lazaroff describes their appearance as such: cutting a finger off a glove, smearing it in Vaseline and dirt, then shrinking it down to less than an eighth of an inch.

“You have this little debris-covered tiny creature underwater that nobody ever notices,” he says.

Lazaroff says freshwater jellyfish reproduce asexually three ways, creating clones of each other — a bud grows on the side of a polyp, developing into a tiny larva, dropping off, crawling away and growing into a new polyp; a bud grows on the side of a polyp, developing directly into a new polyp, which then drops off and lives by itself; or a bud grows, develops directly into a new polyp and remains permanently attached to the parent. All these scenarios produce tiny organisms — most of which we never notice.

But sometimes, freshwater jellyfish reproduce sexually. A bud grows on the side of a polyp — and then that teeny bud grows into a teeny jellyfish.

Pictured to the left is a jellyfish that has come up to the surface in a pool at Sabino Creek in 1988. On the right, you can see another jellyfish, deeper in the water.

Freshwater jellyfish aren't native to Tucson, or even to the United States. Lazaroff says they’re native to China, and there are a few theories on how they made their way here. Thought to be the most likely scenario is that sometimes polyps can fall into a resting state, when they’re covered by a hard coating, almost like a seed, Lazaroff says. It’s possible they get stuck to the foot of a bird, which then migrates from pond to pond.

Lazaroff says the jellyfish are pretty much harmless at Sabino Creek, though. When he spotted them in the ‘80s, there were fish swimming in the same pool of water — and they were simply ignoring the jellyfish.

“The jellyfish might affect microscopic animals in the pond, but that’s not something you and I would ever notice,” he says, adding that the jellyfish could possibly catch a very small fish. There have been a few reports from people saying their hands felt irritated after coming in contact with them, too.

But still, they're a rare sight. The polyps don’t always produce jellyfish and when they do, they might not grow big enough for us to see, or while they’re growing, they might be washed away in running water.

“They’re mysterious creatures,” Lazaroff says.

Tyler Claiborn stands on a rock while watching his daughter play in a pool near the bottom of the Sabino Dam at Sabino Canyon Recreational Area, 5700 N. Sabino Canyon Road, in Tucson, on July 26, 2021.

Another two documented sightings

Lazaroff spotted the jellyfish in a still pool of low murky water, warm at 80 degrees. He had to kneel on a rock to see them.

Some would come up to the surface, before disappearing back into the murky water, Lazaroff says. In his scenario, you couldn’t miss them if you were deliberately looking for them — but if you weren’t, you’d easily walk right by them.

He didn’t need anyone to help him identify the freshwater jellyfish when he saw them — he knew what they were. But he called a friend, a biologist from the University of Arizona, because he knew they’d be interested, too.

By the time the biologist visited the creek in early August, the water started running again.

“That would’ve been the end of the jellyfish,” Lazaroff says.

Lazaroff hasn't seen the jellyfish since then, but there have been at least two more documented sightings in Sabino Creek — in 1999 and 2021 — according to the United States Geological Survey, which allows people to log reported sightings of aquatic species.

Though they’re mysterious and a little bit strange, Lazaroff thinks it’s important to remember their beauty.

“They are exquisite tiny little jellyfish. In China, they are called peach blossom fish, so that’s a nice name for them — it implies the beautiful side of these creatures,” he says.

Lazaroff documented his jellyfish sightings in a sidebar of his 1993 book, “Sabino Canyon: The Life of a Southwestern Oasis.” The book describes the treasured beauty of Sabino Canyon, its plants, animals and recreation. He has another book about Sabino Canyon set to be released this spring.

Before moving to Arizona in 1977, Lazaroff lived in California, where he worked as a high school teacher and a naturalist for the National Park Service. He moved here after accepting a job in Sabino Canyon.

“I found Sabino Canyon to be just a fascinating place — there’s so many things about it,” he says. “It’s interesting in so many ways.

“It has an interesting geology, biology, history — it’s a lot of interesting stuff crammed into just a few miles,” he says. “That’s the thing talking about jellyfish. You can get wrapped up in the strangeness of these creatures, these brainless creatures that reproduce in strange ways, but then you can forget that they’re beautiful and unexpected, floating around in the water.”

Sabino Dam, in the Sabino Canyon Recreation Area, was flowing on Jan. 14, 2023.