New Mexico’s most famous fossilized footprints are every bit as old as they seem, according to a new University of Arizona study that bolsters the case for the earliest evidence of humans ever found in the Western Hemisphere.

In 2021, a team of 14 scientists, including two from the U of A, revealed blockbuster proof of tracks left by people as much as 23,000 years ago along an ancient lake at the present site of White Sands National Park.

The discovery created a stir in the anthropology world, upending nearly a century of consensus around the idea that the first humans did not arrive in North America until about 13,000 years ago.

Critics have been questioning the 2021 findings ever since, mostly by challenging the use of grass seeds and pollen excavated at the site to determine the approximate age of the footprints.

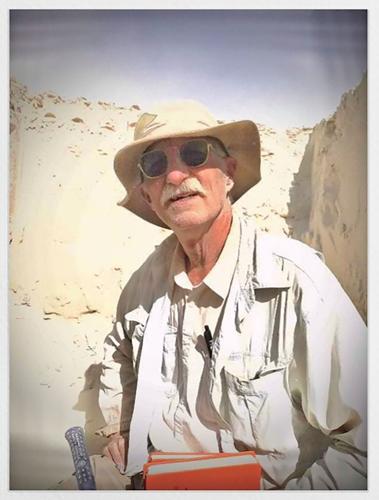

Now, U of A archaeologist and geologist Vance Holliday and doctoral student Jason Windingstad have analyzed mud deposits surrounding the dig site to arrive at a similar age range of between 17,000 and 23,600 years old.

Holliday

“We started doing the radiocarbon dating on the material, and it just matched right up with the tracks,” said Holliday, a professor emeritus in the university’s School of Anthropology who has studied the “peopling of the Americas” for nearly 50 years. “We now have three different sources of carbon tested in three different labs, and all the dates match up nicely.”

Holliday, Windingstad and five other contributors detailed their findings in a research article published Wednesday in the journal Science Advances.

The human tracks at White Sands were left along the bed of a tributary to what scientists call paleolake Otero, a Pleistocene body of water that once filled the valley where the park’s famous dunes now stand.

Holliday said the desiccated wetland also contains the fossilized footprints of several now-extinct large mammals common in North America until the end of the last ice age. There are “tracks all over the place” left by mammoths, dire wolves and giant ground sloths, he said.

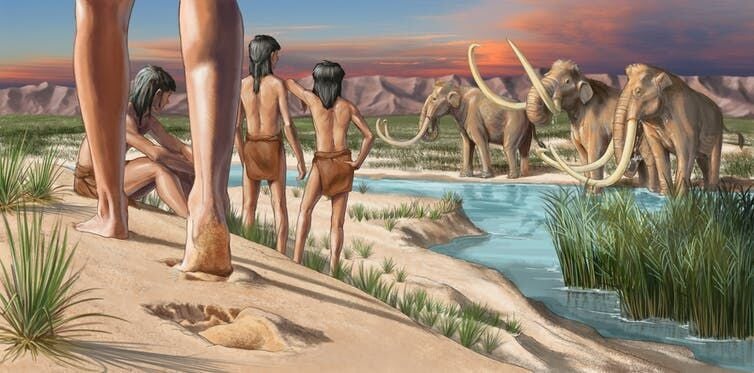

Humans share the shore with mammoths in an illustration of what White Sands, New Mexico, might have looked like about 23,000 years ago.

At one site, human and mammoth tracks cross right over the top of each other. At another, fossilized mud preserves evidence of people following — and occasionally stepping into — the footsteps of a giant ground sloth.

Holliday said he has been conducting field research at the national park and neighboring Holloman Air Force Base and White Sands Missile Range every year since 2012, including his most recent trip just a few months ago.

His previous geology work in the area earned him and one of his other doctoral students a co-writing credit on the now-famous 2021 paper, though the pair was not directly involved in the excavation of the footprints.

His new paper is based on about two dozen mud samples and a few seeds collected from seven different trenches, including five new ones they dug, measuring roughly three feet wide and as much as five feet deep.

The distinctive layers of mud and clay at the heart of the study can be seen along the face of an escarpment where the long-dry bed of Lake Otero continues to erode away, Holliday said. “That’s how we started: picking along the natural exposures.”

A photo taken at White Sands, New Mexico, in 2022 shows layers of olive-green clays lining a hole dug by researchers in the cemented gypsum.

He said he and Windingstad were able to trace those deposits directly to the site where the startlingly old tracks were dug from the ground about five years ago.

“It’s a strange feeling when you go out there and look at the footprints and see them in person,” Windingstad said. “You realize that it basically contradicts everything that you’ve been taught about the peopling of North America.”

Kathleen Springer and Jeff Pigati from the U.S. Geological Survey were two of the leading researchers on the groundbreaking 2021 paper. They called the recent follow-up work by the U of A “a major advance” in the understanding of the overall sedimentary sequence in which the human tracks were found.

As Springer put it in an email, the new paper raises “a very exciting, and yet to be determined, possibility” that people and mammoths might have roamed the same landscape over several millennia, starting as far back as 23,600 years ago.

Since the first human tracks were discovered at White Sands in 2009, researchers have unearthed just over 60 footprints, mostly left by teenagers and children.

Research geologists Kathleen Springer and Jeff Pigati from the U.S. Geological Survey collect seeds embedded in an ancient human footprint for radiocarbon dating during an archaeological dig at White Sands, New Mexico.

Holliday said the tracks provide only the briefest glimpse — no more than about a minute of total walking time — into the lives of humans about whom very little else is known.

“All we know is they were going from point A to point B,” he said. “We don’t know what A and B were.”

And it’s likely no one will ever know. Holliday said half of the Lake Otero fossil record is already “gone from erosion, and the other half is buried underneath the world’s largest pile of gypsum sand.”

As far as he is concerned, though, there can be little doubt anymore that these footprints are indeed the oldest proof of humans yet to be found in the Americas. Two separate research groups have now produced 55 distinct radiocarbon dates that are “remarkably consistent” to that effect, he said.

A 2021 study of these fossilized footprints at White Sands National Park in New Mexico showed that humans were living in the Americas roughly 10,000 years earlier than previously thought. New research from the University of Arizona supports those 2021 findings.

“You get to the point where it’s really hard to explain all this away. As I say in the paper, it would be serendipity in the extreme to have all these dates giving you a consistent picture that’s in error.”

The proof is about as strong as it can get, Holliday said.

“I don’t know what else you could do. Maybe nothing. I think we’ve got as good a story as I have seen told with (radiocarbon dating).”