Luis Ibarra started feeling less energetic in February.

He thought it was a side effect of his diabetes medication. His doctor thought it was a stomach issue and prescribed him pills.

But the pain persisted, so the 42-year-old headed to the emergency room in May. Two hours later, the handyman’s worst fear was confirmed with a CAT scan: His seminoma cancer had returned.

He prepped for his chemotherapy, worried about his wife and their four kids.

Then a week later, he was hit with new symptoms — fever, chills, body aches and no sense of smell. He returned to the hospital and received a second diagnosis: COVID-19.

It took him 2½ months to recover from the respiratory illness, delaying essential cancer treatment. By then, the tumor between his kidney and urethra had grown.

Months later, he’s nearing the end of his third round of chemotherapy, but the pain, dizziness and nausea have made it hard to play outside with his kids or drive them to get ice cream.

His doctor will decide soon whether to schedule surgery to remove the tumor or continue with a fourth round of chemotherapy.

He’s relieved he’s almost done with treatment but constantly plagued by the uncertainty.

Luis Ibarra on September 8, 2020. Ibarra recovered from Covid-19 and then started treatments for seminoma cancer.

“You think you’re going to die,” Ibarra said. “You think, what’s going to happen to your family?”

More than six months after the first case of coronavirus in Pima County, Ibarra is one of a number of residents of Tucson’s predominantly Latino neighborhoods who have been disproportionately hit by the virus.

The rate of COVID-19 cases among majority Latino neighborhoods is more than two times higher than the rate among white majority ZIP codes, according to an Arizona Daily Star analysis of the locations of local cases of the virus.

The Star’s analysis found that Latino ZIP codes have a combined rate of 40 cases per 1,000 people, while majority white ZIP codes have a rate of about 17 cases per 1,000 people.

Individually, four of the five ZIP codes with the highest case rates are majority Latino, on Tucson’s south side. The remaining ZIP code in the top five is majority white and includes the University of Arizona and the surrounding area.

Meanwhile, the five ZIP codes with the lowest rates of infection are all majority white, scattered throughout the county. The Star excluded four ZIP codes from the analysis that are mostly federal land or surrounded by federal land.

The trend has alarmed representatives from the Pima County Health Department, local elected officials, health-care clinics and other advocates who are working to combat the virus in these areas, according to more than a dozen interviews with the Star.

They said the coronavirus hasn’t created issues for these populations but exposed existing ones.

That includes issues like a lack of access to health care and other resources; populations with a higher proportion of existing health issues; a higher number of workers in jobs considered “essential,” meaning they’re unable to work from home or have been laid off; and high numbers of multigenerational housing.

During the course of the pandemic, health clinics, advocacy groups and the Health Department have been providing resources, whether it’s items like masks or hand sanitizer, help with health care, or additional free testing sites.

But many said that’s just a start and that the next step is to focus on those systemic issues.

“It’s important to not just wait for this pandemic to go away and then go back to business as usual. We really need to look at what those disparities are and those inequities are and address them,” said Pima County Supervisor Betty Villegas, whose district includes the southern part of Tucson.

Dr. Francisco García, administrador adjunto del Condado Pima.

Pima County cases mirror national trend

What’s playing out in Pima County is similar to what’s been happening throughout the country, according to public-health experts.

As of Sept. 11, cases among the Latino population totaled 37% of the county’s cases, roughly in line with the county’s 38% Latino population in 2019. But a large chunk, 29% of cases, have ethnicities listed as unknown because people who get tested are not always asked that question.

Dr. Francisco Garcia, Pima County’s chief medical officer, pointed to hospitalization and death data instead, where demographics are known for about 95% of cases. That data showed that deaths and hospitalizations of Latinos outpaced that of the white, non-Hispanic demographic in June, July and August after stay-at-home orders were lifted in May.

There were 175 Latino deaths compared with 170 deaths among white people in those three months, and 726 hospitalizations among Latinos compared with 476 among white people. Pima County was made up of 52% white, non-Hispanics in 2019.

“Racial, ethnic attribution for test data is not perfect, but this is a real trend and this trend is undeniable,” Garcia said, adding that the county is using the demographic data to find hot spots to do additional testing.

Nationwide, Latino populations account for 30% of the coronavirus cases, despite making up 18.5% of the nationwide population, according to data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In addition to risk factors for transmission and severe consequences, minority communities face additional issues, like early scarcity of masks and hand sanitizer, a disproportionate need to use public transit, and higher home density, according to University of Arizona epidemiology professor Kacey Ernst.

That doesn’t include higher rates of comorbidities — the simultaneous presence of two chronic diseases in a patient — less access to medical care, and massive job losses that got even worse, causing security and nutrition to suffer.

“Many of these communities face structural inequities; built on sites with massive levels of pollution and food deserts. Work exposures are higher. Structural racism and discrimination impacts stress and health, and these all manifest in disparate health outcomes — higher heart disease, diabetes, asthma, etc.,” Ernst wrote in an email.

In Tucson, south-side communities have faced a number of issues contributing to their health, such as contaminants in water, high rates of air pollution and lack of access to resources, according to Paloma Beamer, a UA public-health professor.

Garcia added another issue contributing to the spread — culture.

As a Latino, he said he understands it’s difficult not to hug or kiss people, especially family members. He said Latinos tend to be more social, but they are also the people working essential services jobs.

“It breaks my heart because I feel like the Grinch, but there should be no quinceañeras, there should be no big weddings because we should not be gathering,” Garcia said. “Especially bringing older people into those gatherings is just crazy and can only hurt us.”

Low-income households are, in general, more at risk of food insecurity or eviction due to job loss. High school counselors in majority-Latino districts report their students are going to work to help support their families after parents have lost jobs.

“What’s been so heartbreaking this summer is we’re coming face to face with systemic problems that we already had. I think the pandemic has highlighted those further on top of them,” Beamer said.

With health care, it’s all about access

When he was at the hospital the second time, Luis Ibarra’s wife, Marcela Robles, 40, was also diagnosed with the virus. So was his daughter, Chelsea, 18. The latter two experienced aches and fevers.

Their son, Luis, 7, and daughter, Amanda, 3, both had fevers and were presumed positive. Their oldest, 23-year-old Sheyja Robles, the only family member who doesn’t live at the house, caught the virus while driving her dad to his doctor’s appointments.

While all six members of the family recovered, they weren’t without issues.

In addition to delaying the father’s cancer treatment, none of them has health insurance.

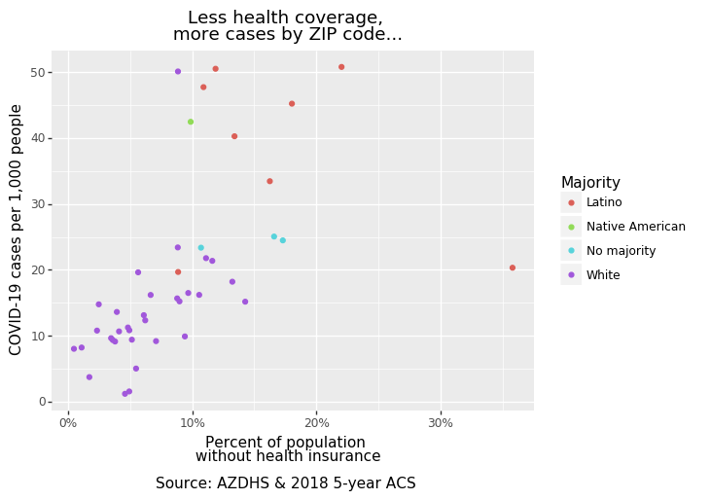

In Pima County, the majority Latino ZIP codes have some of the highest rates of people without health insurance, according to the most recent 2018 five-year estimates by the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey.

Those ZIP codes also tend to have higher rates of COVID-19 cases, according to the Star’s analysis. Overall, the infection rate in ZIP codes where 15% to 20% of people don’t have health insurance is three times higher than in ZIP codes where fewer than 5% of people are without coverage.

Residents of these communities typically rely on relief funds or clinics from government health-care programs, such as the Affordable Care Act and AHCCCS, Arizona’s Medicaid program, according to David Martinez III, director of capacity building and community engagement at the Vitalyst Health Foundation. Those who are undocumented don’t qualify for government health insurance.

In Martinez’s experience, not qualifying for government programs causes some immigrants to fear seeking help, which affects their ability to access the resources they need, especially during a pandemic. Those resources can be as simple as feeling safe going to a doctor’s office.

“To that point, people of color, especially the Latino community, because of that mistrust, have fear of accessing resources because of the erosion of trust,” Martinez said. “And fear that even among a mixed-status family with members of the household that have American citizenship that they’re putting their family at risk.”

During the pandemic, filling that gap of coverage has largely fallen to health clinics in some of these areas. That includes El Rio Health, which has provided coronavirus testing for free to patients — and should they test positive, their families — regardless of whether they have insurance.

El Rio Health has adapted during the pandemic, providing telemedicine appointments. It has also provided support through its foundation, such as giving families gift cards for essential goods like groceries.

“What we forget is that people who are not documented are the people who didn’t receive anything like the stimulus check or anything, so those are the people who are just left out there,” said Catalina Laborin, manager of advocacy and community resources at El Rio.

“With El Rio, not only do we have that connection, but we also have that trust, that confianza,” Laborin said. “So I think it was easier for people to come in and be tested and get the care that they needed.”

Church friends help Ibarra family get by

That’s been especially helpful for Luis Ibarra, who has been unable to do his handyman work, fixing plumbing, laminating floors or basic electric work, since March. Sheyja, the only other family member who works, chips in money for gas from her job at a home remodeling company.

“The most difficult thing for me personally has been not being able to work, not being able to provide for my family,” Luis Ibarra said.

Friends from their church, Sonrise Baptist Church, whom Ibarra called his “brothers,” helped with bills, delivered meals and provided support. El Rio, where Ibarra gets his diabetes medication, has helped pay for chemotherapy.

The Oncology Institute of Hope and Innovation near St. Mary’s Hospital, where Ibarra gets his treatment, was able to provide a $4,000 dose of a bone marrow stimulant to Ibarra for just $17 through a copay program.

That’s allowed him to focus on fighting the cancer for a second time, having had a tumor removed in 2009.

Each round of his current treatment includes three weeks of chemotherapy, sometimes having treatment every weekday.

It was difficult learning his treatment would take longer, he said, because the chemotherapy can be painful and uncomfortable.

But while he has no money in his pockets, he’s just happy he doesn’t have any debts.

“I’m really grateful to (El Rio) and to the people from church and from the clinic,” he said, crying.

Dr. Sudha Nagalingam, a health-care provider at El Rio Health, checks patient Kyle Haney. Nagalingam is part of the clinic’s incident command team for COVID-19.

Humberto Gurrola traveled to Sinaloa, Mexico, in early June to attend his brother-in-law’s funeral. He returned to Tucson already feeling sick and feverish.

His son, Nicolas, 22, took him to the emergency room. Humberto, 69, was discharged that day but learned he tested positive for the virus on Father’s Day.

He continued to test positive every two weeks over the next two months, left to isolate in a room in the family’s south-side home. His wife, 49-year-old Dina Mendoza, left food and medicine for him at the door.

While Mendoza and her son continued to test negative, she couldn’t sleep most nights, stressed and worried that his age could bring health complications, and that her diabetes could put her at risk should she contract it.

“He wouldn’t tell me he was feeling ill to not stress me out,” she said.

Gurrola used to work for a construction company, but he lost his job a year ago when the company closed. Before the pandemic, Mendoza sold tamales and babysat for extra money. Nicolas works about 32 hours a week at El Super grocery store.

On his fifth test, Gurrola tested negative. But the family realized they couldn’t pay their rent and bills with only their son’s income, so they’ve been forced to move into their niece’s house temporarily.

“My world fell apart,” Mendoza said.

ZIP codes where a higher percentage of households have more than one person per room also tend to have higher rates of COVID-19 cases, according to the Star’s analysis.

“Octopus on steroids”

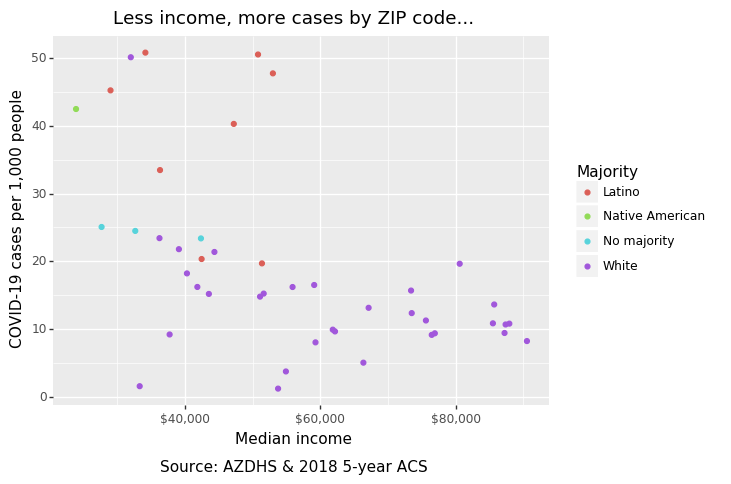

The same is true about income. ZIP codes with a higher median household income also tend to have lower infection rates.

Fallout from the virus has been like an “octopus on steroids,” according to Lydia Arranda, president of Chicanos Por La Causa Southern Arizona, referring to the fact that one problem has been leading to another.

That’s been especially true in terms of personal finances. Moratoriums on evictions and utility payments have helped, but debt is mounting, she said, adding that her group has been working on attacking these issues.

Latinos have also been hit harder by rising unemployment, according to Mignonne Hollis, executive director for the Arizona Regional Economic Development Foundation.

Many Latinos work essential jobs and either face layoffs or have the inability to work from home. In Pima County, the top industries for Latinos are health care and social assistance, followed by accommodation and food services, data shows.

After the economic shutdown in March, the seasonally adjusted unemployment rate for the Latino population more than tripled to 19% in April, compared with the record-high national unemployment rate of nearly 15% in April, Bureau of Labor Statistics data shows.

Unemployment has declined steadily since then, but in July the unemployment rate for Latinos was still nearly 4 percentage points higher than the national unemployment rate of 13%.

The Pima County Health Department and Paradigm Laboratories are offering free COVID-19 tests at the Kino Event Center located at 2805 E. Ajo Way.

Those numbers also don’t account for people who work gig jobs, such as landscaping or maid work. Many are noncitizens and are ineligible for unemployment or federal loans.

“It’s really shining a light on the issues that were already there,” Hollis said. “A lot of issues aren’t new issues to us, they are just now at the forefront and, quite frankly, getting worse.”

The situation is similar to what’s been seen at Clinica Amistad, a volunteer-run clinic near West Irvington Road and South Sixth Avenue that provides care for its mostly Latino patients at no cost.

Its patients often lack resources, are essential workers and often live in multigenerational households, according to clinic manager Francelia Garcia.

“tight-knit” community is hit even harder

Latinos are more likely to live in multigenerational households compared with white families, according to an analysis of 2016 census data by the Pew Research Center. That year, 27% of Latinos lived with multiple generations compared with 16% of whites.

“Our patients are hardworking people who cannot afford to miss a day of work. So many are exposed in that work environment. Then, unfortunately, they expose the rest of the family members because they all live in the same home, helping each other out with rent or food, whatever they can to support one another,” Garcia said.

Francisco Valencia was born and raised in the Old Pascua neighborhood, nestled in a pocket near Interstate 10 and West Grant Road. His favorite memories were the cultural ceremonies, which eventually encouraged him to run for tribal council when he turned 25.

Now in his fourth term, he’s worried by the shadows emerging over his neighborhood as buildings rose in nearby downtown. That caused rising property taxes, leaving some friends and others close to him homeless. Others in the community have succumbed to alcoholism and drug addiction.

“We’re so tight-knit, so it’s more visible,” said Valencia, who serves as secretary for the Pascua Yaqui Tribal Council.

Valencia has also seen his community hit hard by the virus — even if it hasn’t hit them individually. He said at least 25 members of the Yaqui tribe in Arizona have died from the virus. That includes about a dozen in Tucson.

“Every single family member of the tribe has been, in one way or another, affected by COVID-19,” he said.

Pima County has only one majority Native American ZIP code. It covers Tohono O’odham land and has had about 42 cases per 1,000 people, the ZIP code with the sixth-highest infection rate in the county as of Friday.

The most recent data from the Pima County Health Department shows that cases among the American Indian population represent 3% of the county’s total cases, exactly reflecting that community’s 3% share of the county’s population in 2019, although that doesn’t account for missing demographics. Native American deaths represent 4% of the total.

Communities in Old Pascua, like many of the surrounding neighborhoods just west of Interstate 10, are plagued by “decades of disinvestments,” according to Mary Ellen Brown, an assistant professor with the Arizona State University School of Social Work in Tucson.

That lack of access to resources has caused a domino effect, she said. Something like a school closure has left youths without a gathering place after school. Some kids have to watch their siblings while their parents work multiple jobs. Others turn to crime or drugs to fill the time.

A lack of school lunches leaves them with gaps in nutrition, leading to higher rates of comorbidities.

“People are just trying to survive,” said Brown, who is also the director of ASU’s Office of Community Health, Engagement and Resiliency.

As part of her work, including through a program called Thrive in the 05, she’s been focused on working on “investing in people.” That includes simple things, like passing out household supplies to those who can’t afford them during the pandemic, or creating after-school programs.

During the pandemic, the office has also created a phone bank to overcome issues of loneliness caused by physical distancing.

“Complex problems require complex solutions,” she said.

For the Pascua Yaqui in Old Pascua, what’s helped them, like always, is coming together as a community, according to Valencia. Like last Friday, when they held a drive-thru giveaway of goods and resources at their neighborhood center, with bags of household supplies and masks.

Attacking the inequities is always ongoing. The tribe just celebrated its 42nd anniversary as a sovereign nation, affording it access to some resources — and money, which officials have spread across their communities in Arizona and elsewhere.

Tribal officials have also been working on economic development initiatives.

But Valencia acknowledged that tribal officials often feel stuck without access to adequate resources.

“Historically, thanks to our elders and the perseverance of our elders and the resiliency of our elders, we’ve been able to overcome many obstacles ... and call the Old Pascua community our home,” he said.

Short-term patches, long-term fixes

For Eva Carrillo Dong, a member of the Sunnyside Unified School District Board and a longtime advocate on Tucson’s south side, the numbers are “not pretty.”

But they are also just numbers.

She personally knows people who have gotten sick and died, others in the hospital or others who were bedridden. She said she feels like her neighbors are living the realities that are often used as political talking points.

“The stories I hear are just so devastating. You just wish you had a zillion dollars to help every single one of these people,” she said. “I’m one person who’s hearing these stories. Can you imagine how many stories are out there?”

She said she sees a lot of parallels between the pandemic and the 2008 economic recession. She feels that existing issues have worsened and, without help, she doesn’t expect them to be gone any time soon.

“The effects on our community are going to be devastating,” she said.

Villegas, the Pima County supervisor, said she could see from the beginning that her district was being hit harder than other parts of Tucson.

She and her staff started looking into the numbers and pinned the problems on inequities, like a large number of people working in essential jobs.

She formed a focus group that meets biweekly to diagnose and fix any short-term issues it can. They’ve done efforts like mailing out masks and educating the community.

But she admitted it’s been hard at times to get the Tucson community to care about the outbreak in Tucson’s more-vulnerable areas, comparing it to outrage over outbreaks near the UA.

“It was great to mobilize that quickly to the students, but my frustration was in the fact that we could not do the same on the south side of town,” she said, adding that her district includes students and that combating the outbreak was also “the right thing to do.”

It’s been a similar story for Mayor Regina Romero, who also noticed hot spots emerging on the south side of Tucson.

The biggest issue, Romero said, was just awareness of the issue. She started doing videos daily in Spanish to spread awareness about local mitigation efforts.

While both politicians said the short-term fixes, which have included efforts to provide more testing access on the south side, have been effective, they need to be part of a larger conversation to deal with systemic issues.

Villegas said now is the time to discuss systematic policy changes in the realms of public health, public transportation and education, all in an effort where it’s “not about equality but equity.”

Romero said it’s the responsibility of the city, county, state and federal government to combat those issues. She said she and the Tucson City Council have been trying to take that equitable approach during the pandemic, whether it was declaring a climate emergency, expanding internet access to families for schooling or working from home, and rent and utility assistance.

“COVID-19 is going to be with us for a long time,” Romero said. “I don’t even want to think about it.”